Apps or the web? For Google, at least, the answer is now clear: It’s both.

The company announced Instant Apps on Wednesday (May 18), hinting at a future when apps and the web merge into nearly indistinguishable experiences. Instead of downloading apps, Android phones will soon be able to selectively download chunks of code that run the parts of the apps needed to play a video, sell an item, or book a hotel room.

That’s welcome news for Steve Miller, the CTO and founder of the mobile location service Glympse. He says the difficulty of sharing his app’s data with anyone (users must download Glympse to access most of its services) remains the biggest barrier to signing up new users. “With Instant Apps, we can show a light-weight version of the app,” said Miller in an interview. “It’s phenomenal for us.”

Google’s nearly two-year effort aims to marry the convenience and openness of the web with the fast and fluid interaction of apps. Developers have struggled with this dilemma for years. The promise of the web has always been tearing down barriers for people to talk, discover, share, and work together online. All you need is an internet connection and a browser. Native apps were something new. On smartphones and tablets, you suddenly had fast computing power, lots of local storage for your data and content, and a silky-smooth interface. It made the web, especially with slow connections, felt stodgy.

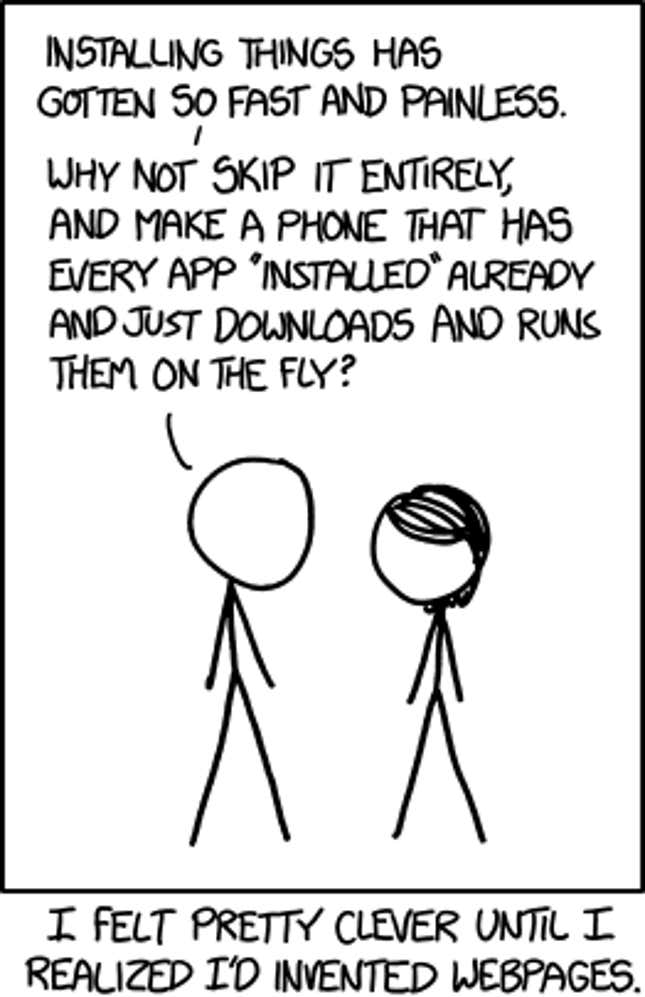

But the cost was high: You can’t share and discover most of what happens in apps with others unless they own the app as well (and sometimes buy into the entire Apple or Google ecosystem). It essentially “breaks” what’s so great about the web. This problem is neatly summarized in the tech-focused comic xkcd:

Instant Apps is one way tech companies are trying to solve this challenge. It works like a webpage, but is still an native app on the phone. The technology lets someone using an app share things on the web with a URL. Anyone can click on the link and it will run only the parts of the app needed to watch, shop or share something. No installation is necessary, as Android downloads bits of the app in the background.

Google says the webs-versus-app debate is secondary to the importance of giving users and developers a great experience on any platform. “People want to hear that we have a grand plan to kill off one or the other,” said Ficus Kirkpatrick, a Google engineering director leading Instant Apps, during Google’s I/O conference. “I think the idea of the death of either one is really overrated. Both keep getting better. The lines are really blurring.”

Indeed, developers are hard at work building browsers to make the web work more like apps by offering offline functionality, personal data storage, direct access to sensors and processors, and lightening-fast computing. App creators, meanwhile, are eager for an escape from the confines of people’s home screens and labyrinthine app stores, one that allows users to share their apps’ content and functionality on the web.

Instant Apps is just one of several emerging technologies that promise to bridge the gap between web and native experiences. One of those is progressive web apps, which Google announced in 2015. Progressive web apps work like conventional websites in the browser, but add native apps’ most desirable features: They work offline, run on multiple devices, save user data, and can be installed on phones. Once visitors return to a site several times, a notification asks if they would like to install the app on their home screen, effectively a link to the browser where their data is stored. Flipkart, India’s largest e-commerce site, has already moved its service to a progressive web app and others are doing the same. The technology is gaining traction, although it does not yet have widespread adoption, in part because not all browsers support the technology, developers need to retrofit existing sites, and native apps can still outperform it for computing-heavy applications.

Streaming apps are another promising technology. Apple and Google have both released support for apps that can run directly from the cloud. These use little or no installed software, and serve up an app after a user opens it, instead of downloading the entire package. Each company has taken a slightly different approach. Google’s App Streaming service now powers previews in search results for some Android apps, and replicates the entire app experience on the fly. It only requires a fast wifi connection. Apple’s On Demand Resources lets developers install a small core application on users’ phones, and then download other content and data as needed.

Google plans to release the Instant App technology later this year, though BuzzFeed, B&H Photo, Medium, Hotel Tonight, and others are already in beta trials.“It’s a big change in how we think about apps, and we want to get it right,” said Google product manager Ellie Powers at the I/O conference.

It may not be long before the battle between native apps and websites looks silly. We’re moving toward a future where there may not be much difference. Already, the grid of apps on a phone’s home screen is starting to look outdated, as functions are carried out via notifications, widgets, and search. Ultimately, the only user interface you’ll need to get things done on your device may be written or spoken requests. Just ask Apple’s Siri, Google Assistant, or Amazon Echo.