He bobbed his head with the groove, and leaned way in when he wanted to play more complicated melodies, rocking and rolling with the beat of the jam. This wasn’t a your average jazz band member, though—this was Shimon, a four-armed robot marimba player built by the Georgia Institute of Technology to be able to listen to music, improvise, and play along with human musicians.

At a performance at Moogfest, a four-day music and technology festival in Durham, North Carolina, Gil Weinberg, the lead researcher at Georgia Tech’s Center for Music Technology, demonstrated what he and his lab have been working on for the past 12 years. Their efforts have aimed at augmenting the creative capabilities of humans with robotics. That can mean robots like Shimon, which uses machine-learning programs trained on music theory and a wide range of musical styles, from chamber music to dubstep, to be able to add a superhuman element to musical performances, playing chord structures that would be physically impossible for humans to hit.

But it can also mean robotic enhancements for humans: At the concert, Weinberg introduced Jason Barnes, a drummer who lost the lower part of his right arm a few years ago. Barnes had, through connections, sought out Weinberg in the hopes of being able to drum again. Barnes said he just wanted a robotic prosthesis that would recreate the functionality of drumming. But Weinberg worked on doing him one better, creating a robot arm with two drumsticks that he could control with the muscles in his bicep that could drum at up to 20 beats per second.

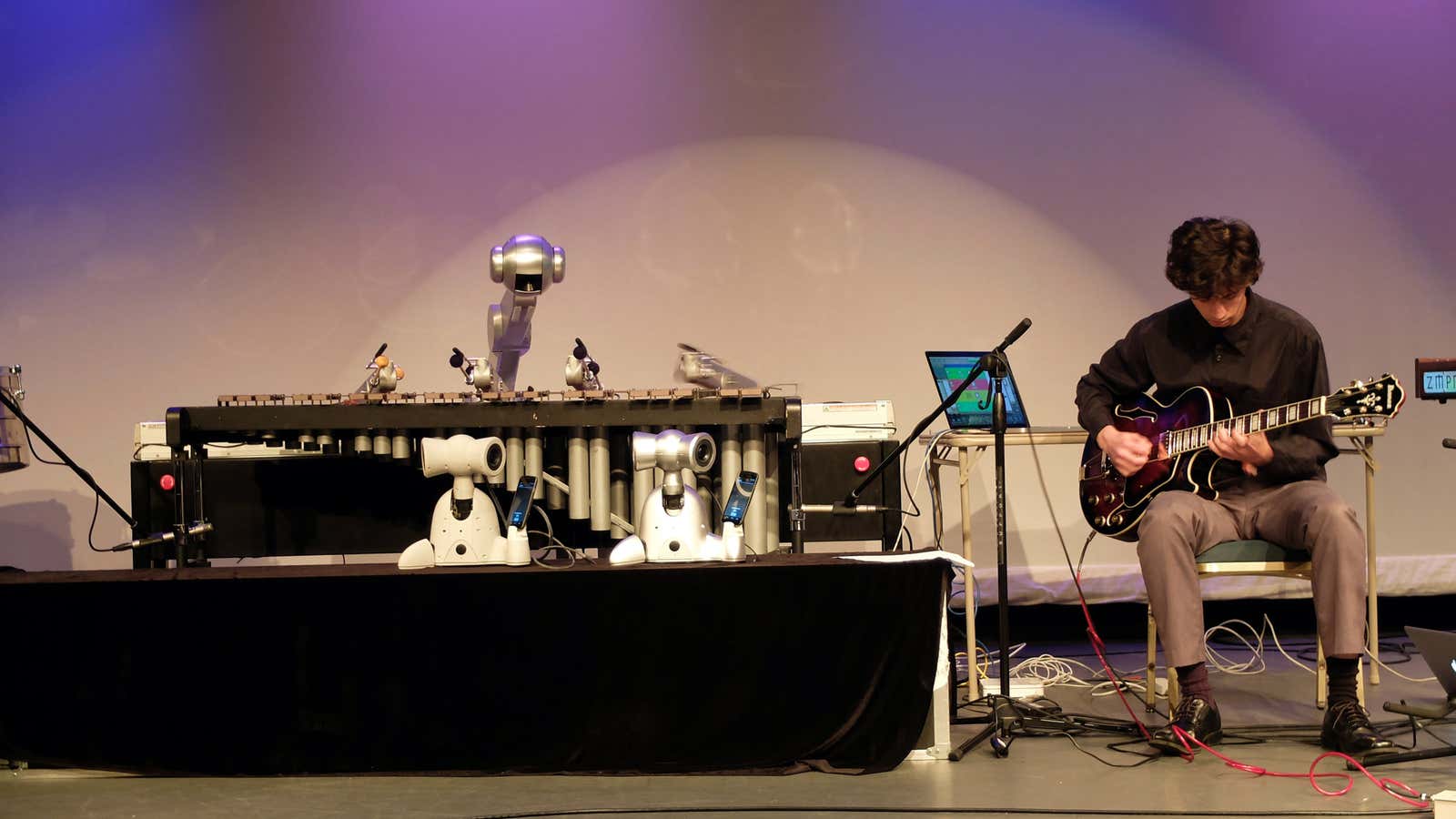

Barnes joined Weinberg, his team, and Shimon onstage to play a few songs, and the performance was pretty surreal. A man was playing drums faster and with greater accuracy than perhaps every other drummer on earth (although Weinberg said that jazz guitarist Pat Metheny said his drummer apparently could play that quickly), accompanied by a robot marimba player that was improvising as well as the humans, and seemingly just as into the performance as they were. On top of that, Weinberg brought out two other robots he’s developed, called Shimis, that acted almost like backup dancers, who bobbed their heads and tapped their feet in time with the music. (I’ve been to many concerts composed entirely of humans that weren’t nearly as energetic as the Georgia Tech robot band was.)

Weinberg’s team is now working, as Quartz previously reported, on a strap-on prosthetic arm that anyone could wear which can listen to a beat and drum along with them. His students are also working on making Shimon’s creative abilities even stronger, currently working on figuring out what it would sound like if it was fed one style of music and asked to play another, such as feeding it Mozart and asking it to play jazz in the style of Thelonious Monk.

Weinberg’s team isn’t the only group of researchers working on using artificial intelligence to create music and aid musicians. Even at Moogfest, a group from IBM’s Watson team showed off a new capability of its AI system that allowed it to take musical inputs, select a music style, and have it output a fleshed-out piece of music, that they hope to make available to developers and tinkerers soon. But unlike IBM or many other researchers using AI systems for music, Weinberg’s team is building working robots that can play real acoustic instruments, rather than programs that output beeps from a speaker. Much like with real musicians, who use eye contact and gestures to communicate to their band members when they’re going to change keys, start choruses, or end songs, Shimon can gesture in much the same way, and look for its bandmates’ gestures. Weinberg said it can “listen like a human, and improvise like a machine.”

Perhaps in the future, generations of aspiring musicians will look up to robots as they do humans today. Or perhaps we’ll all just be able to be superhuman cyborg musicians jamming out at lightspeed, thanks to Weinberg’s work.