A Canadian traveler I met in Cuba’s uber-touristy enclave of Varadero told me she had made a point of booking her trip for this year, so she could catch a last glimpse of the Communist-ruled island before it changes.

She got there too late. Our mojitos already had mint.

The first time I went to Cuba, in 2001, the country’s signature white-rum-and-lime cocktail arrived sans its traditional garnish. As the island struggled to bounce back from the Soviet Union’s collapse ten years earlier, there was simply no mint to be had.

To be honest, I can’t really remember much that’s worthy of nostalgia from those days. Despite the lengthy menus, the only fare at state-owned restaurants was chicken and rice. Old Havana was crawling with “jineteros,” or hustlers trying to extract whatever they could from tourists—a night out, a few dollars, some extra toiletries—and I couldn’t blame them. Aside from those interactions, Cubans and foreigners were separated in an apartheid of sorts, with each group assigned to their own transport and paying a different set of prices.

It was bleak. What got to me wasn’t the scarcity of material goods, or even the lack of freedoms we take for granted elsewhere in the world. It was the hopelessness that seemed to hang in the air, like Havana’s asphyxiating heat—the palpable frustration of people all too conscious that they weren’t going anywhere.

Cubans are going places today, and that’s evident in Havana’s now lively streets. Pedicabs and yellow Coco-taxis, which look like giant motorcycle helmets on wheels, zigzag around, hauling tourists and Cubans. Brand-new Chinese buses have replaced the hulking monster buses known as camellos, or “camels,” public-transit Frankensteins made from welded Soviet buses and pulled by trucks. Vendors push wooden carts mounded high with garlic and guavas.

It seems every other doorway has a sign selling something or other, including, to my delight, potent jolts of cafecito, or Cuban expresso, which I missed during my previous trip.

To be sure, the majority of Cubans still experience poverty and scarcity, but in the week I was in Havana recently, the people I encountered struck me as a lot more cheerful and less desperate than 15 years ago. One night I asked if I could buy a cigarette from a woman who was puffing on one outside a tattered facade, as Habaneros do to catch the ocean breeze. She chuckled.

“Honey, the situation is bad, but not that bad to sell a cigarette,” she said, offering me one. We smoked together.

Here are a few of the things that have changed in Cuba for the better. I, for one, hope it keeps changing.

Transportation

Back in 2001, almendrones, or the iconic 1950s American cars that serve as public transit, were pretty much reserved for Cubans. Foreigners were relegated to newer state-owned taxis, with rapidly-climbing meters and straight-laced government-employed drivers. The one time I managed to sneak into an almendrón, I was booted out after a couple of blocks when the driver realized I wasn’t local.

These days most taxis are driven by independent workers, or cuentapropistas. The rate is negotiated ahead of time, an arrangement that makes taxi-driving a lucrative profession. It took me several expensive rides priced in CUCS, or Cuba’s convertible currency that trades one-to-one with the dollar, to figure out that I, too, could pay much cheaper fares.

It costs only 10 Cuban pesos, or less than 40 CUC cents, to catch an almendrón on one of several pre-established routes that crisscross Havana. You just have to know the right hand gesture to hail an almendrón that’s headed where you’re going. (Ask any Habanero for an education on this. One even gave me a 10 Cuban peso bill when I told him I only had CUCs.) The same applies to longer trips outside of Havana. I paid a small fortune for an air-conditioned car to take me to a small town I wanted to visit. On the way back, I caught a brand-new Chinese bus for eight CUCs. It was also air-conditioned, and I had a lovely conversation with my seat mate.

Food

During my first visit to Havana, paladares, or independent restaurants, didn’t have signs up. You had to know where to find them. Guided by locals, I sat at a couple to escape state restaurants’ chicken-and-rice fare. The food was much better, though the menus still fairly limited.

I couldn’t find any seafood, a puzzling predicament on an island with 3,600 miles of coast. I only got to eat some because I illegally hired a fisherman to catch some octopus for me, which he delivered still wriggling on a metal coat hanger to the casa particular, or private home, where I was staying.

If you weren’t eating at someone’s table, it was hard to buy food. All I could turn up at small community markets were brown-skinned oranges. I remember feeling overjoyed upon finding a pile of bruised, overripe mangoes scattered on the pavers of a courtyard. I stashed several in my bag after asking for permission.

Today there are wonderful things to eat, at Cuban and foreigner prices. For 50 Cuban peso cents, I bought homemade guava pastries from the woman who baked them, but I also paid US prices for artisanal chorizo prepared by an Italian chef at an impeccably-appointed restaurant in el Vedado, a neighborhood known for its beautiful mansions. I ate scrumptious flan made in makeshift molds of cutoff beer cans at a old-school paladar, and amazing Peruvian ceviche garnished with lots of pickled red onions at O’Reilly 304, a tiny, hip place in Old Havana.

These days there’s even an app to help visitors navigate Havana’s growing culinary bounty. And in another welcome development, the places I visited were filled with Cubans, not just foreigners toting a copy of Lonely Planet.

Shopping

I have nothing but pictures to remember my first Cuba trip. I couldn’t find anything to buy, not because I was picky, but because there was very little for sale. Cubans actually asked you for stuff—aspirin, pencils, candy.

There’s lots to buy today. A lot of it is what you would imagine: T-shirts and caps of dubious quality, straw hats and all manner of kitschy Che Guevara merchandise.

There’s nicer stuff too. If you arrive early enough, you can load up on some excellent Cuban coffee beans at state-run shops. (I found that they usually run out by the afternoon.)

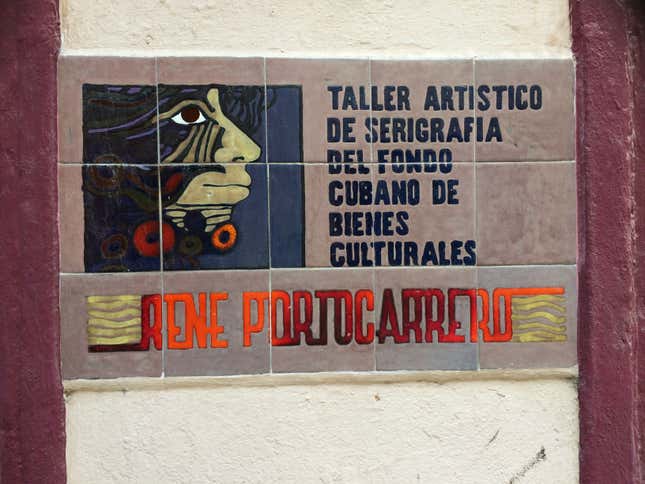

I also bought four gorgeous prints for less than $80 at the René Portocarrero serigraphy workshop in Old Havana. Chatting with the artist who made them was free.

Just flip through the digital pages of Amano, a design magazine highlighting Cuban creations, to find other cool souvenirs.

People to people

For all the newfound comforts and treats of traveling in Cuba, my favorite part of my most recent trip was interacting with its people. I found them to be much more in the mood to talk than 15 years ago. Whether sitting in a taxi cab or on the stoop of an open doorway, I was able to really visit with Cubans this time around. It was like being a guest in someone’s living room drinking coffee practically the entire time.

My mission was different from a tourist’s. I was there as a journalist. But even in the moments when my notebook was tucked inside my purse, Cubans seemed eager to tell me about their country and explain all its quirks. They had lots of questions for me too.

A cynic might say Cubans have simply caught on to the hospitality game that prevails elsewhere. The happier and more welcome tourists feel, the more they’ll tip and buy. I like to think they’re friendlier and more open because they are in a better place.

I’m also happy to report that mojito mint is plentiful.