Alexander McQueen, the celebrated fashion designer who committed suicide in 2010, liked to provoke. His 2001 asylum-themed collection, for example, culminated with a fleshy, nude woman reclining in a glass cube, breathing through tubes connected to a face mask as large live moths fluttered around her.

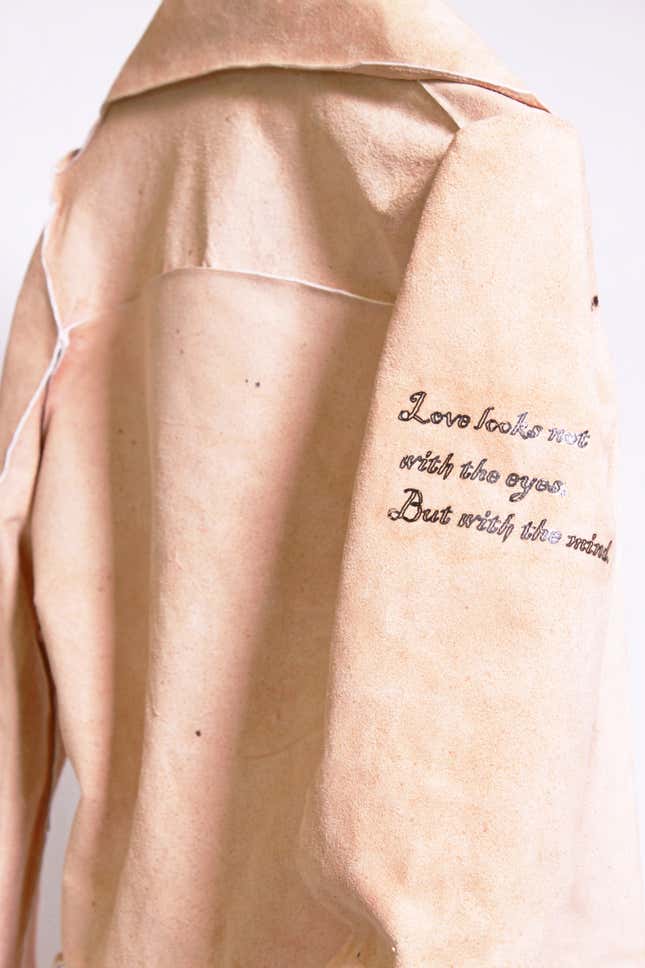

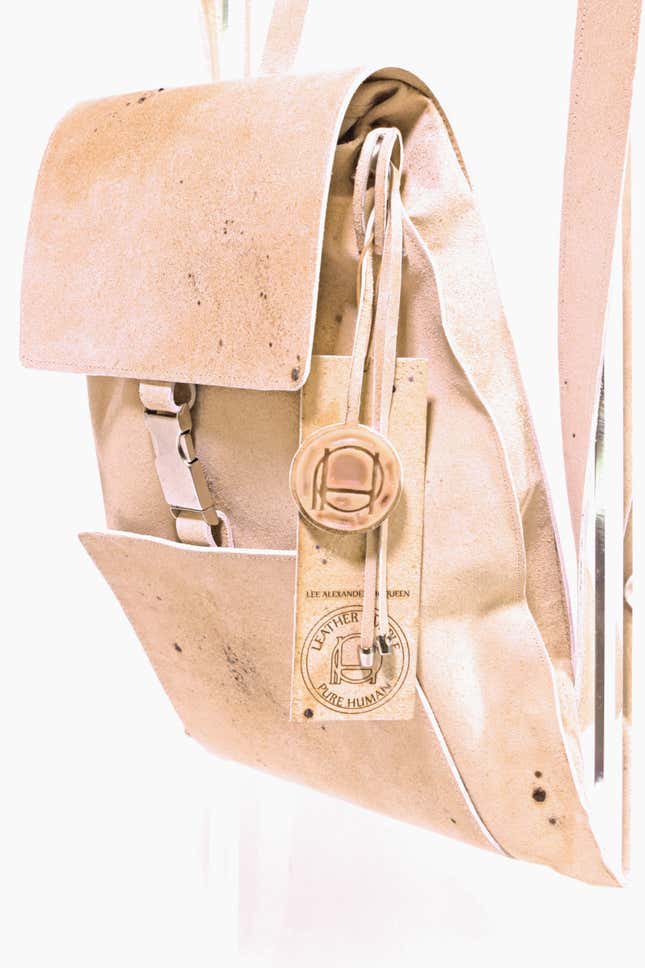

So it’s reasonable to think he would have approved of a new project based, literally, on his life. Tina Gorjanc, who is just finishing the material futures program at McQueen’s alma mater, London’s famous fashion school Central Saint Martins, is working on a project that will use McQueen’s DNA to grow skin, which she plans to tan and turn into leather jackets and bags. The skin will even bear tattoos based on the exact “locations, size, and design,” of McQueen’s, she says.

The lab manipulated the genes that control freckles and moles as well, and the skin can get sunburned. “With the tattoos and manipulation of freckles and sunburning, I wanted to showcase the material,” Gorjanc explains. “I think that was really important in terms of getting this connection between the jacket and McQueen.” Recently she presented her “Pure Human” project in an exhibition, using products made of pig skin to show what the final items could look like.

Gorjanc’s project is intended to raise questions about how corporations might one day exploit genetic information for luxury goods, and to showcase how little protection exists for a person’s DNA. In May, she filed an application to patent, as she describes it, “bioengineered genetic material that is grown in the lab using tissue-engineering technology and the process of de-extinction.” De-extinction allows you to extract genetic material from a deceased source.

She’s not able to patent McQueen’s DNA itself, but says if she is granted the patent, she would “have ownership of this material that includes Alexander McQueen’s genetic information.” She also filed a second patent for the process, separate from any connection to McQueen.

Though she has been approached by some who want to produce the items for sale, Gorjanc says the finished products would more likely be displayed in a gallery. She would consider selling them to a collector, but is more focused on the technology, which might be useful in creating sustainable, lab-grown leather that doesn’t require slaughtering animals.

The DNA to grow the human skin will come from McQueen’s hair, which he used in his 1992 collection, “Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims.” It referenced the Victorian era, when prostitutes would sell locks of their hair that people would purchase to give to their lovers. McQueen confirmed in interviews that it was his own hair he used, and Gorjanc spoke to a friend and model of McQueen’s who was with him when he put the hair in the labels, so she says she’s reasonably sure it is authentic. The institution that owns the collection—she wouldn’t say which it is—has agreed to give her a sample of the hair.

Gorjanc, who has a long fascination with biotechnology, got the idea for the project after reading about the case of Henrietta Lacks, a poor, black tobacco farmer in the US whose cells were taken without her knowledge in 1951. Those cells have since been vital to medical research on everything from the polio vaccine to cloning. Her story was told by Rebecca Skloot in the hugely popular book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

Gorjanc also found out that luxury companies are investing in bioengineering, though she says it’s mostly for the purpose of testing cosmetics on skin and to reduce animal testing.

How much ownership a person has over their genetic information is still a fuzzy area of law. In 1984, for instance, a doctor in the US patented a cell line derived from the tissue of a man named John Moore. Moore, who didn’t know his tissue was being used, lost his legal battle to win the rights to the patent.

Glenn Cohen, an expert on the intersection of bioethics and law at Harvard Law School, says it’s “very common” for researchers to take tissue and use it for research. These days, however, patients are usually asked to sign a form agreeing to give away those biospecimens and relinquish any commercial interest, he says.

In the US, you also have no ownership of “abandoned” tissue, such as hair left on the floor after a haircut, though again, nobody can patent the DNA itself.

Ownership law in the UK is even less stringent. “The standard rule in the UK is that there’s no ownership property right of human tissue,” says Dr. Jeff Skopek, a lecturer in medical law, ethics, and policy at University of Cambridge. “So McQueen didn’t own his hair, technically. That’s what’s called the ‘common law property rule.'”

Gorjanc says she consulted with a patent attorney, and that what she’s doing is “completely legal.” But she, or anyone else in the UK attempting to use a deceased person’s DNA, likely faces legal challenges, according to Skopek. The UK’s Human Tissue Act, for instance, often demands a person give informed consent before their tissues can be used. McQueen did not in this case. Gorjanc may need approval from a research ethics committee. The Data Protection Act might also apply.

There’s more leeway if the tissue is anonymous, but in this case, it is very much not.

Though Gorjanc says she has been in touch with the Alexander McQueen brand, the company says it did not have prior knowledge of the project. “Contrary to some press reports the company wasn’t approached about this project nor have we ever endorsed it,” a spokesperson said. McQueen had no children, though his father and five siblings (paywall) survived him.

Gorjanc says she did get some feedback from those who knew McQueen. “People that were really close to him or that worked for his institution said that he might actually like the idea,” she says. “He was always pushing the boundaries and always trying to break laws in fashion.”

An earlier version of this story quoted Gorjanc saying she spoke with the Alexander McQueen label about the project and got a positive reaction. Quartz had reached out to the label but had not received a reply at publication time. After this story was published, the company reached out to say that Gorjanc had never approached them about the project.