A military coup attempt is underway in Turkey, with the Turkish Armed Forced claiming to “have completely taken over the administration of the country to reinstate constitutional order, human rights and freedoms, the rule of law and general security that was damaged.”

This is just the latest in a string of military coups spanning the second half of the twentieth century. The Turkish military, which had lost significant power under president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has long considered itself—and has been considered by some (pdf, p.56)—a guardian of the country’s democracy, due to a history of intervention to maintain secularism in the country.

Military officials were arrested for allegedly being part of a secret organization called Ergenekon which was already trying to overthrow Erdoğan while he was prime minister, in 2002. But even before that, the army has seized control of the government of modern Turkey, often to defend against perceived threats to the strong secularity desired by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the former army officer founder of the Republic of Turkey.

May 27, 1960

This coup took place at a moment when the ruling party, breaking away from the strict rules imposed by Atatürk, began to allow religious practices, including the opening of hundreds of mosques and permitting prayers in Arabic.

When the army took power, coup leader Cemal Gursel declared that “the purpose and the aim of the coup is to bring the country with all speed to a fair, clean, and solid democracy,” and that the army aimed to hand over power to a democratically elected government. Gursel eventually held power as prime minister and president until 1966.

Mar. 12, 1971

Tensions within different sides of Turkey’s political spectrum and economic stagnation led military general Memduh Tağmaç to initiate what is known as a “coup by memorandum.” Rather than a straight-out military intervention, he gave then-prime minister Süleyman Demirel an ultimatum, demanding “the formation, within the context of democratic principles, of a strong and credible government, which will neutralize the current anarchical situation.” The memorandum led to Demirel’s resignation. The military didn’t directly seize power, overseeing instead a series of transitional governments that lasted till 1973.

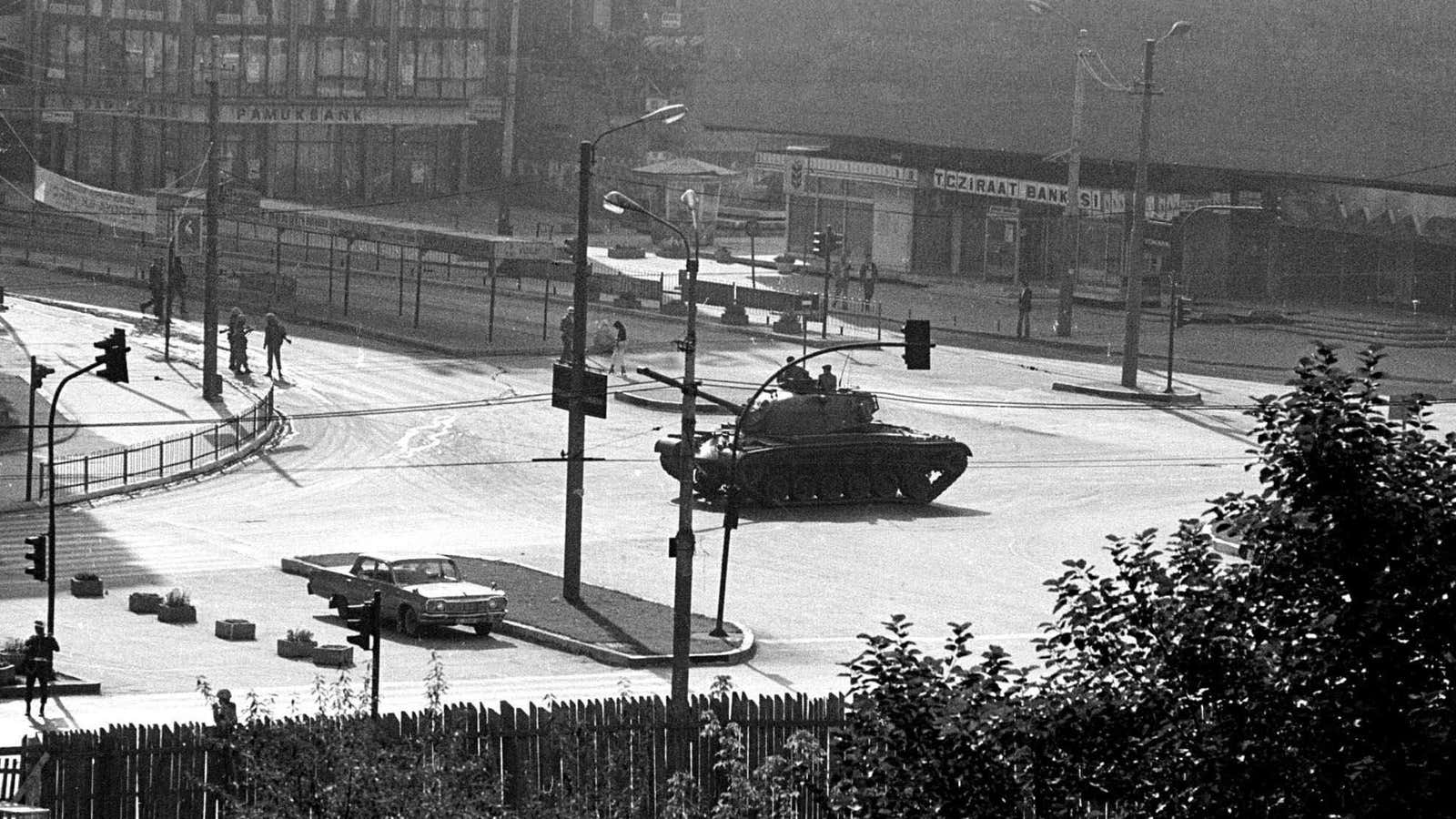

Sept. 12, 1980

The social and political situation in Turkey didn’t quite settle after 1973, and once again the military took matters into its hands. Toward the end of 1979, some high-ranking Turkish officers decided to initiate a coup, which was originally scheduled for March but happened months later. On Sept. 12, a coup d’état was declared on national television, together with the announcement that martial law would be imposed on the country.

The constitution was revoked and substituted with another that was put to a referendum in 1982 and approved by 92% of the voters. With the new constitution in place, elections took place. Kenan Evren, one of the generals who led the coup, remained in power as president for the following seven years.

Feb. 27, 1997

The military took control of the country again with what was famously labeled a “postmodern coup,” during the presidency of Süleyman Demirel (who had previously been overthrown as prime minister by the 1971 coup.) Concerned about an increasing presence of political Islam in the country, a group of generals led by İsmail Hakkı Karadayı presented the government, led by Necmettin Erbakan, with another series of recommendations—including closing many religious schools, and banning the wearing of headscarves at universities. The generals then forced the prime minister to resign. A temporary government was formed and the military eventually forced the Welfare Party out of power in 1998.

That same year, Erdoğan, who was then mayor of Istanbul, was sentenced to jail and banned from politics for five years after publicly reading an Islamist poem. New elections were held in 1999. Erdoğan was elected president in 2014.