We’re used to thinking of the internet as a place that exists apart from our physical presence in a particular country. I can send an email to someone who lives in New Zealand as easily as I can to someone next door. When I do, thousands of independent computer networks whisk my message around the globe without regard for the walls, mountains, oceans, or border fences that stand in the way. There are no import tariffs, national taxes, or customs agents to deal with. There are, it seems, no national borders on the internet.

Slowly, that fiction is coming apart. The infrastructure of the internet exists in real places and governments are awakening to the idea that they can use that fact to regulate what we do online. Increasingly, each country wants to control the internet in the same way they do financial transactions, immigration, or the postal system. If your data crosses enters their territory they want to be able to inspect it, count it, and—not yet, but maybe someday—tax it.

The internet doesn’t have borders that clearly delineate where one country’s legal jurisdiction stops and the next country’s begins. Yet rules crafted by one country have implications for users everywhere. For example, EU courts have used their homegrown ”right to be forgotten” to insist that search engines remove links for all users in the EU, regardless of whether or not they are EU citizens. Google, despite being an American company, has removed nearly 600,000 such links. French regulators have gone even further, insisting that Google also remove those links around the world. A similar case is now before the supreme court of Canada. None of these decisions would be legal in the US.

In the absence of any uniform global regulation, this tangle of local decision-making raises complex issues. Do countries abide by one another’s laws? Do they refuse? Do they censor foreign websites that fail to comply? If France is allowed to unilaterally export its laws via the internet, then why not Turkey? Or Saudi Arabia?

For internet-natives, it is tempting to frame any threat to the independence of the internet as one of doddering old governments trampling on the youthful spirit of innovation. However, the dangers of not enforcing domestic laws are also real. As criminal threats move online, so must the tools governments use to combat them. How can a government protect the privacy of an email account held by a private company halfway around the world?

Over the last few years, privacy and national security have developed into wedge issues, which are driving countries apart. As national priorities harden into law, the internet risks being fragmented into 100 little pieces—what some have called a “splinternet.” So far this process has been slow, but that makes it all the more risky, because for the most part it is also completely invisible.

The internet’s layered model

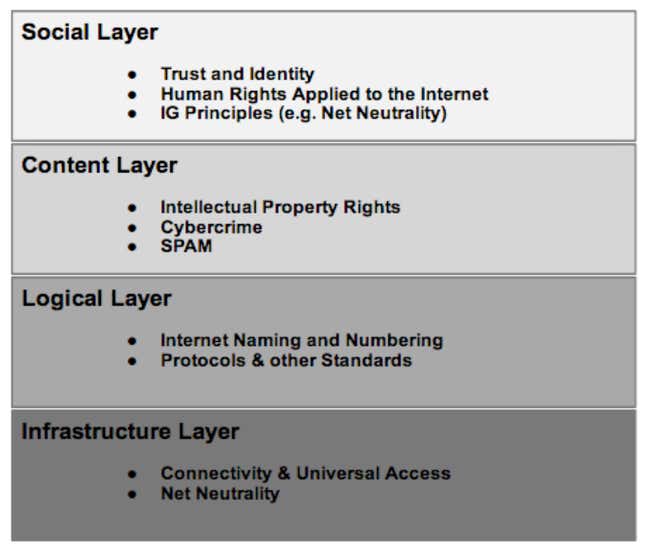

Though few people are aware of them, there are international organizations that govern the internet. Groups such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), and the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) set standards and handle distribution of limited resources, such as domain names. Vint Cerf, widely credited as the man responsible for devising the protocols that make up the internet, has written about the difficulties of governing the internet’s many parts. In a 2013 paper written with Patrick Ryan and Max Senges, he mapped out the layers of the internet.

Each layer in Cerf’s model corresponds to a bundle of internet features that are built on those below and necessary to those above. For example, the Domain Name System (DNS), which maps names such as “qz.com” to internet addresses, sits at the Logical Layer because it is built on networking technology from the Infrastructure Layer, and facilitates the publication of websites at the Content Layer. In theory each of these layers can be governed in isolation of the others. His bullet points describe some of the issues relevant to each layer.

Most of today’s internet battles, such as those over censorship and identity theft, center on Cerf’s Content and Social layers, which are where users actually interact with one another. These are, not by coincidence, the parts of the internet that the traditional governance organizations, such as ICANN, tend to avoid. Those organizations have long advocated a hands-off policy when it comes to what is and isn’t allowed on the internet. In the absence of official oversight, the United States has sometimes acted as a de facto global regulator, if only because most so-called “internet giants” are based in the US, and thus subject to US law.

Today that central power is diminishing. Some of this is by design—everyone agrees centralized authority is a bad design for an international institution. Other changes are driven by the rise of new internet superpowers, such as China, who rightfully want a seat at the table.

As power has diffused, disputes have arisen over how best to control, store, and transmit data while safeguarding (or, in the case of repressive regimes, handcuffing), the rights of a country’s citizens. These issues lie squarely in those unregulated, upper layers of Cerf’s model where users live. Into that power vacuum stepped Edward Snowden. His 2013 revelation that the NSA was scooping up massive amounts of internet traffic single-handedly raised the profile of data flowing across international borders. In his wake many countries are moving aggressively to protect their users from the prying eyes of the US government.

How to barricade the internet

The techniques for accomplishing this are not new to the internet. China has partially isolated its internet users for more than a decade. However, the privacy issue is also leading to strict controls in places that traditionally were more comfortable with allowing the United States and international governance organizations to chart their own course. Those countries are now reaching out to fill the rule-making gap at the top of Cerf’s internet layer cake with their own, national ideals.

In Europe, this has led to a raft of data-protection laws aimed at protecting citizens’ privacy. The most important of these is the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which was adopted earlier this year and will come into effect in 2018.

At the core of the GDPR is the idea that the EU should be able to regulate the internet for its citizens, no matter where the services they use are actually hosted. For example, under the new rules, a website that sells software EU citizens will be subject to EU privacy laws, even if that company is headquartered in Korea and has its data centers in the US. For the first time, companies that fail to comply could be slapped with huge fines. Many are bracing themselves for a new era where once-toothless data protection regulators enforce their powers more readily.

“It’s certainly given [privacy regulators] more prominence, and in some ways it’s long overdue,” said Lillian Pang, a senior legal officer at web hosting firm Rackspace.

There is a legal precedent for the GDPR. In 2014, the European Court of Justice ruled that Google’s US search service would be subject to European privacy law, specifically Spanish law, when it came to privacy complaints. This included the “right to be forgotten,” which allows EU citizens to request specific search results be scrubbed from Google’s index. The courts concluded that because Google offered a localized version of its search services targeting Spanish residents (pdf), the data processed by Google’s US search service fell under the purview of Spanish privacy law.

In addition to expanding European influence outside EU borders, the GDPR also includes provisions that encourage data to be kept at home. In particular, companies are not allowed to transfer data outside the EU if the destination country does not have adequate privacy safeguards. Any company that handles a large volume of personal data will be required to appoint a Data Protection Officer, who reports to the EU on its compliance efforts. Regulators can also audit companies they believe are skirting the law. French lawmakers further proposed, but eventually rejected, a rule that would have required French citizens’ data to always be stored in the EU, without exception.

Forcing local storage is another way governments ensure that their citizens’ data remain under the umbrella of their laws. In particular, it guarantees they will have access in the event of a criminal investigation, intellectual-property dispute, or other legal conflict. To the extent that such laws also ban companies from keeping duplicate copies in other countries, they may also be an effective way to prevent foreign surveillance.

Russia recently passed its own data localization law. Brazil and India are considering similar measures. Many other countries require it for certain kinds of data. Bit by bit, Cerf’s top layers are being sliced up.

The problem with making deals

One skilled explorer of the conflicts between national laws on the internet is the Austrian privacy activist and legal provocateur Max Schrems. It was Schrems who, as a law student, brought down the Safe Harbour agreement, a trans-Atlantic privacy deal that had allowed EU data to be legally processed in the US since 2000. Safe Harbour was a relatively lax self-certification system that allowed US tech giants to establish European operations with little fuss.

In 2013, Schrems pulled the thread that eventually unwound Safe Harbour. He put in a routine request to the Irish data-protection authority for the information Facebook had collected on him. Snowden’s revelations had just hit, and when Schrems received reams of data back from Facebook, which had been stored on US servers, he filed suit against the Irish authority. How could his data be safe, he argued, when the NSA had probably sifted through it while it was stored on American servers?

Eventually, Europe’s highest court agreed with him, and in December 2015, Safe Harbour was struck down. It was invalid because it didn’t protect EU citizens’ data from US government surveillance, the court ruled.

Much wrangling commenced to find a replacement, which has now been formalized, called Privacy Shield. The new agreement gives Europeans extra safeguards against US government surveillance, like the newly created office of an ombudsman in the US State Department. But the process of writing it was a rushed and nervous one, with officials often working late into the night, and with the sense that policy-makers were desperately papering over a crack that was growing too large to deal with. Today, the Privacy Shield is a done deal, but Schrems and other observers believe it will be a matter of time before it, too, is deemed inadequate by the EU’s highest court.

If personal data is the new oil, as the cliche goes, then surely agreements like Privacy Shield are the obvious way to negotiate the workings of the internet. However, such treaties are slow to produce, inflexible, and difficult to generalize. Imagine going one by one and negotiating a separate deal with every country that has internet users. Ideally, countries would get together and make at least some decisions as a group, but a multi-country agreement seems almost impossible given the awkward and disagreeable process that produced Privacy Shield. If the US and the EU have a hard time agreeing, it’s difficult to imagine a successful agreement that includes Brazil, China, and India—countries with huge numbers of internet users, but wildly different political and legal systems. According to Christopher Kuner, a European privacy lawyer, “There isn’t […] any real political will to have a wide-ranging international agreement on any of this.”

Cerf has argued that treaties are precisely the worst way to approach internet governance. ”As the globe looks toward governance systems for the Internet in the next phase, we should avoid the temptation to enshrine arcane rules in international treaties,” he wrote (pdf).

He appeals to his own utopian ideals, calling for countries to empower (and pay for) the patchwork of NGOs that have overseen the internet’s growth to date. That means organizations like ICANN, the IETF, and the IGF, which Cerf himself is a key member of. He puts his faith in the sort of rough and ready negotiations that gave birth to the internet. ”In some ways, it is the tussle that matters the most—and the willingness of the stakeholders to engage with each other and attempt to work out the policy equivalent of “rough consensus and running code,” he wrote, citing a popular canard about how internet technology decisions are made.

The slippery slope

Cerf’s vision for empowered, independent decision-making isn’t likely to materialize anytime soon. In the absence of international coordination, internet companies may find themselves in the unenviable position of having to satisfy contradictory legal requirements. According to Vivek Krishnamurthy, an instructor at Harvard’s Cyberlaw Clinic, “Companies that happen to be headquartered in the US are going to face more and more conflicting legal demands, including demands that may require them to violate US law in order to comply with the law of another country.”

As an example, Krishnamurthy describes a hypothetical case where a foreign state is seeking email held by an American company. The foreign country might supply enough evidence to satisfy its own laws, but not enough to get a warrant in the US. Even storing data separately in each country might not be enough to allow a company to legally, much less ethically, satisfy both laws.

More fundamentally, there is a question about the legal nature of data flowing over the internet. Scholars disagree about whether data has exceptional properties, such as unprecedented mobility and divisibility, and thus should be exempt from existing legal principles that depend on “territoriality,” or pinning down data’s location. “Data is everywhere and anywhere and calls into question which ‘here’ and ‘there’ matter,” according to Jennifer Daskal (pdf), an associate professor at American University. On the other hand, maybe data is not special at all. Money and debt are intangible assets that have similar properties, and they have been successfully governed for centuries, as Andrew K. Woods, an assistant professor at the University of Kentucky has written (pdf).

In a worst-case scenario, it’s easy to imagine all these disagreements pushing the world to a point where each country has “an internet” that stops at its borders. That shouldn’t sound too far-fetched: China already has exactly that and Russia seems to be actively pursuing the same thing. Services which fail to comply with local laws get blocked, either through onerous fines or outright bans. Domestic alternatives fill in the gaps, such as Sina Weibo and WeChat in China, or Yandex and VK in Russia. In a future in which a lot more countries apply these sorts of controls, communication across borders will effectively require a layer of national censorship. How else can you prevent foreign services from skirting the rules?

That isn’t to say every state will use those regulations to suppress its citizens, but rather that the internet itself risks becoming balkanized to the point where communication between people in different states is a much more bureaucratic affair. If the US and Europe arrive at fundamentally incompatible rules for privacy online, does that mean they will need to negotiate a treaty in order for me to be Facebook friends with someone in Belgium? Will there be a tariff on Skype calls? A tax on email?

Until recently, the countries of the world were a bit like colleagues periodically meeting for dinner. With the exception of China and a few others, they all showed up, ate together, and split the check at the end of the night. But as more countries choose to project their local laws onto the internet they are, in effect, choosing to stay home. Each dinner has fewer and fewer guests. That’s what could happen if the internet continues to fragment—a slow separation that eventually ruins the party.