Here’s the thing: I liked the new Woody Allen movie, Café Society. I didn’t want to like it; I actually went into the screening hoping I wouldn’t like it. But with the compelling love triangle, the 1930s Hollywood glitz, the old-school references and quick wit, I found myself laughing, feeling, and really caring. I left the theater charmed and completely entertained.

Herein lies the uncomfortable, ongoing reality of being a Woody Allen fan. How do you reconcile liking the art despite the ongoing rumors and accusations that surround the artist? To recap, Allen’s adopted daughter Dylan has repeatedly and publicly accused her father of molesting her as a child. Allen denied the allegations in a New York Times op-ed in 2014, but his case is not helped—at least in the court of public opinion—by Allen’s marriage to his partner Mia Farrow’s adopted daughter, Soon-Yi Previn, who is 35 years his junior. This question of art vs. artist has come up in relation to various artists throughout history—Sean Penn has a public history of violence, John Lennon admitted to hitting his first wife, and Bill Cosby allegedly sexually assaulted dozens of women, to name just a few.

Perhaps it’s Allen’s special brand of neurotic confidence. Perhaps it’s the type of accusations levied against him. Perhaps it’s the inherently unprovable nature of his guilt. Whatever it is, Woody Allen seems to raise some of the most complicated questions about art and culpability in the 21st century. This complication becomes further nuanced by legal ambiguity. Are we not to consider Allen innocent until proven guilty? But then again, what if he will never be proven guilty because of statutes of limitations? Furthermore, where do you draw the line when considering which artists to damn and which to continue supporting?

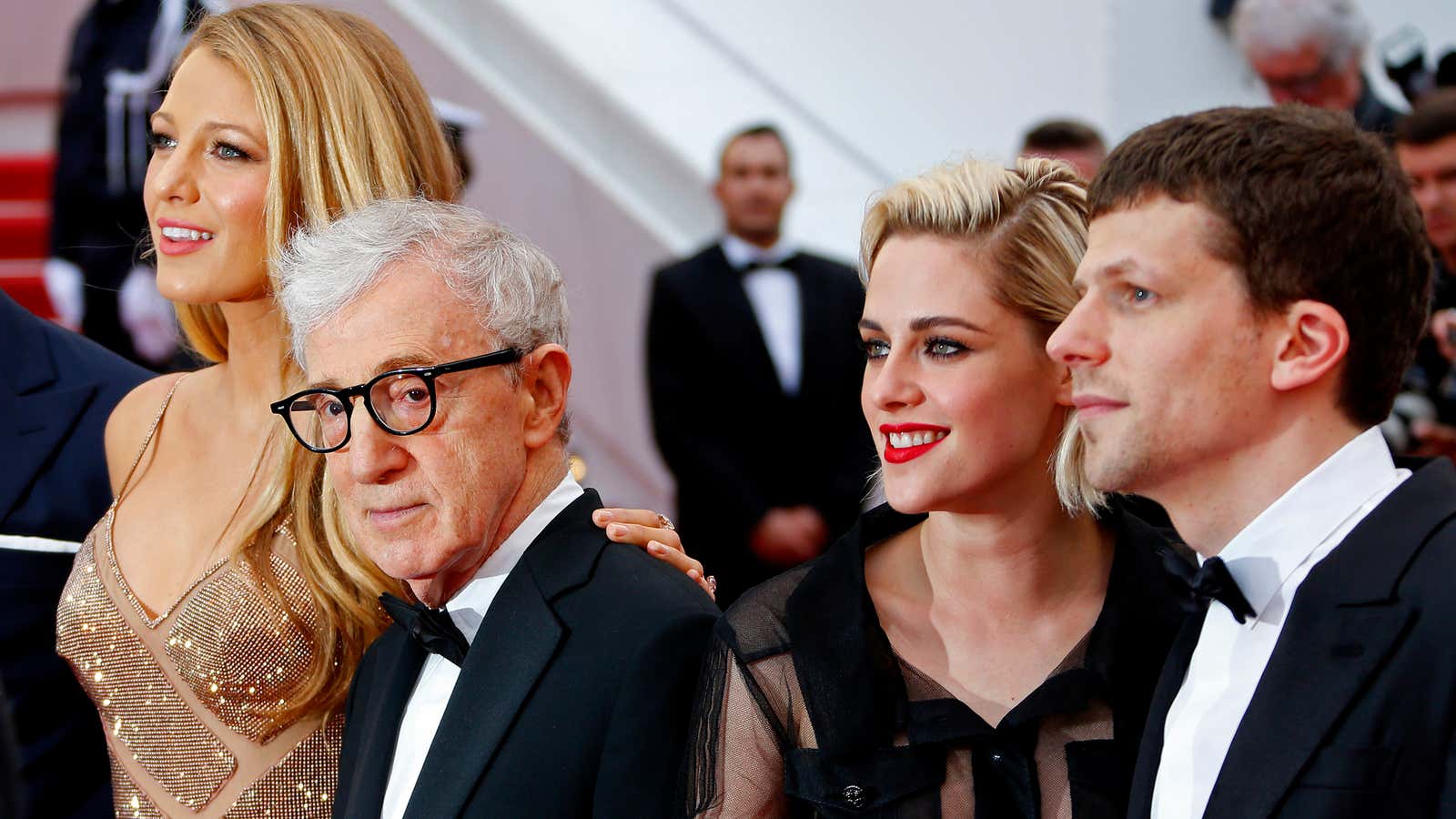

Allen’s newest movie, which opened on Friday (July 29), tells the story of Bronx boy Bobby Dorfman (played by Jesse Eisenberg) who heads west to seek his fortune in Hollywood. While there he hits up his powerful uncle Phil (Steve Carell), and falls for his uncle’s assistant Vonnie (Kristen Stewart). A love triangle ensues, and Blake Lively shows up—as do themes we’ve seen in Allen’s films before, including a May-December romance.

This last theme is a particularly thorny one for Allen audiences. Allen consistently links young female leads with much older male ones, with Manhattan being the best-known example. Given his well-trodden domestic history, such plot wrinkles hit a little too close to home for many, almost feeling like the breadcrumb droppings of a guilty plea. Rather than shying away from the whispers, he charges straight into them, making the line between art and life especially murky.

Dylan’s accusations have done little to halt her prolific director father’s production schedule. Faced with what is becoming a bi-annual debate over the ethics of viewing Allen films, artists like Lena Dunham have made clear how they divide their loyalties between the man and his movies. “In the latest Woody Allen debate I’m decidedly pro-Dylan Farrow and decidedly disgusted with Woody Allen’s behavior,” Dunham said. “But for me, when people go through his work and comb through it for references to child molestation, that’s not the fucking point… I’m not comfortable living in a world where art is part of how we convict people of crimes.”

Others, like Allen’s son Ronan Farrow, have taken harsher stances. Around the time of Café Society’s Cannes premiere, Farrow wrote an article in the Hollywood Reporter criticizing the media for its often tight-lipped acceptance of his father’s films. “That kind of silence isn’t just wrong. It’s dangerous,” Farrow wrote. “It sends a message to victims that it’s not worth the anguish of coming forward. It sends a message about who we are as a society, what we’ll overlook, who we’ll ignore, who matters and who doesn’t…it’s time to ask some hard questions.”

The fact that Allen has suffered relatively few consequences stands in contrast to the treatment of other artists, such as Bill Cosby. Allen’s legacy may never be quite the same after his allegations, but Cosby’s career was legitimately destroyed; networks pulled re-runs of the Cosby Show, whereas Allen was given his own Amazon series. The simplest answer may be that Allen has only one accuser while Cosby has dozens, and as the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates put it (back when only 15 women had spoken out against Cosby), “Believing Bill Cosby does not require you to take one person’s word over another—it requires you take one person’s word over 15 others.” For whatever reason, Allen’s accusations exist in gray while Cosby’s seem to occupy a space of black and white.

So what are we, as moviegoers, meant to do? Boycott Allen’s films? Watch the films but refuse to pay at the box office? Decide if the value of Allen’s creative genius outweighs his alleged misdemeanors?

The reality is that very few people are able to watch a movie without injecting some of our own contextual biases into it. As one of the lessons explored in Café Society dictates, the past can’t be outrun. There’s a filter we see Allen’s work through now, and it’s not one chosen by the artist. And yet, perhaps there is still space for us to appreciate the work, even if we condemn the mind behind it. As Ronan Farrow wrote, we must keep asking questions, but we also must be satisfied with the idea that we may never get the answers.

Follow Elena on Twitter @eleshepp. We welcome your comments at ideas@qz.com.

Correction: An earlier version of this article referred to Mia Farrow as Woody Allen’s ex-wife. The two were in a 12-year relationship but were never married.