Santiago Swallow may be one of the most famous people no one has heard of.

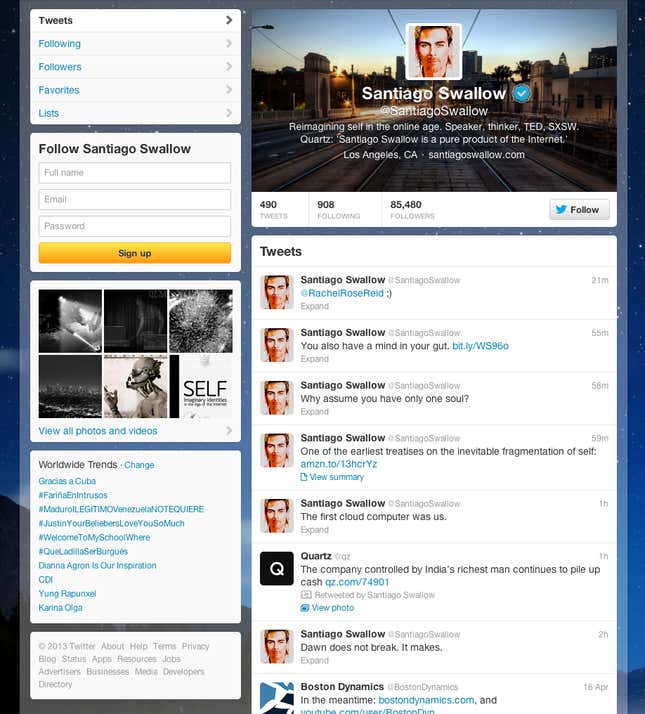

His eyes fume from his Twitter profile: he is Hollywood-handsome with high cheekbones and dirty blond, collar-length hair. Next to his name is one of social media’s most prized possessions, Twitter’s blue “verified account” checkmark. Beneath it are numbers to make many in the online world jealous: Santiago Swallow has tens of thousands of followers. The tweets Swallow sends them are cryptic nuggets of wisdom that unroll like scrolls from digital fortune cookies: “Before you lose weight, find hope,” says one. Another: “To write is to live endlessly.”

Swallow is a pure product of the Internet: a “speaker and thinker,” who specializes in “re-imagining self in the online age,” an apparent star of the prestigious TED (Technology, Entertainment and Design) conference, and a hit at Austin’s annual art, technology and music event, South By South West (SXSW). His Wikipedia biography explains why: Swallow is “a Mexican-born, American motivational speaker, consultant, educator, and author, whose speeches and publications focus on understanding modern culture in the age of social networking, globally interconnected media, user generated content and the Internet,” who has “dedicated himself to helping others know more about how media and personality can be manipulated in the 21st Century.” Famous for its “neutral point of view,” Wikipedia also reports that Swallow’s opinions are controversial in some quarters, especially his prediction that “the disassociation of self would lead to a revision of the standard definition of Multiple Personality Disorder to include selves that only manifest in the online world.” He can be expected to take up this argument in his book, Self: Imaginary Identities in the Age of The Internet, due out later this year, something that his Wikipedia biography, his official web site (santiagoswallow.com) and his Twitter feed all confirm.

There’s just one thing about Santiago Swallow that you won’t easily find online: I made him up. Everything above is true. He really does have a Twitter feed with tens of thousands of followers, he really does have a Wikipedia biography, and he really does have an official web site. But he has never been to TED or South By South West and is not writing a book. I—or rather he—flat out lied about that. (Editor’s note: Santiago Swallow’s Twitter account was suspended after the publication of this piece. After about 30 hours the account was reinstated. In the meantime, a fake Santiago Swallow Twitter account named @SwallowSantiago appeared.)

Creating Santiago and the online proof of his existence took two hours on the afternoon of April 14 and cost $68. He was conjured out of keystrokes in a matter of minutes. I generated his name on “Scrivener,” a word processor for writers and authors. I turned the “obscurity level” of its name generator up to high, checked the box for “attempt alliteration,” and asked for 500 male names. My choices included Alonzo Arbuckle, Leon Ling, Phil Portlock and Judson Jackman, but “Santiago Swallow” just leapt out as perfect. I gave Santiago a Gmail account, which was enough to get him a Twitter account.

Then I went to the web site fiverr.com, the online equivalent of a dollar store, and searched for people selling Twitter followers. I bought Santiago 90,000 followers for $50, all of whom would, he was assured, appear on his Twitter profile within 48 hours. Next I gave him a face by mashing up three portraits from Google images using a free trial copy of Adobe’s “Lightroom” image manipulation software. I gave Santiago his “Twitter verified account” check box by putting it onto his cover image right where his name would appear. It will not fool many people, but might give him a little extra credibility with some. By the time I uploaded these images to Twitter, Santiago had developed a large “following,” even though he did not have a profile and had never tweeted anything.

To get him tweeting, I used a trial copy of TweetAdder, which automatically tweets, follows and retweets on Santiago’s behalf. His breezy platitudes come from half a dozen “mad-lib”-like phrases of the “if this, then that” variety, coupled with a list of nouns from the new age TED/SXSW hipster vocabulary: dolphins, phablets, Steve Jobs, mobile, Tom’s shoes, stevia and so on. To get his Tweet count up as fast as possible, I set TweetAdder to spit out these jewels every minute or two and hooked him up to retweet select other Twitter users, mainly from the “religion and faith” category—plus, of course, Quartz.

Last, I wrote Santiago’s Wikipedia biography—trying for something that would not attract the immediate attention of Wikipedians on the lookout for scams and self-promotion. I borrowed the biography of management thinker Peter Drucker, deleted most of it and rewrote the rest, making Santiago an expert in the fake TED-ish field of “the imagined self.” His web site cost $18 from WordPress.

Making up—or at least “enhancing”—an identity like this is something real people do to increase their reputation, look popular, and sell themselves. There are equally real people who profit from this by selling fake followers created by software at the push of a button. Twitter is awash with fakers with fake friends, many with self-created Wikipedia biographies and most of whom position themselves as “professional speakers,” “experts,” or something similar. The people in the middle—the rest of us—get duped into thinking someone is more popular than they are.

On social media, it is easy to mistake popularity for credibility, and that is exactly what the fakers are hoping for. To most people, a Twitter account with tens of thousands of followers is an easy-to-read indication of personal success and good reputation, a little like hundreds of good reviews on Yelp or a long line outside a restaurant. Looking online to learn more about somebody has become a reflex—blind daters do it, potential employers do it, potential customers do it.

Specialist social media analytics companies do it too. These businesses claim they can analyze somebody’s social media behavior and accurately evaluate their level of influence. One of the best known is “Kred,” a service provided by San Francisco company PeopleBrowsr. PeopleBrowsr says its customers include consumer goods giants Procter & Gamble and Budweiser and major advertising agencies Ogilvy & Mather and Wieden + Kennedy. Less than a day after he was invented, Santiago Swallow had a Kred influence score of 754 out of 1000. According to a free white paper Kred sent him, Santiago is living in a “new era of consumer influence: when nobodies become somebodies.”

If companies like PeopleBrowsr are so easily fooled, it is easy to see how other people might be taken in too. How can thousands of Twitter followers be wrong?

Consider Sandra Navidi. According to Wikipedia, Navidi is a “frequent media contributor,” who has “a global network with access to key decision-makers,” “frequently appears as a keynote speaker and panelist all over the world,” and “provides financial markets analysis that has resonated in the financial community.” On Twitter, Navidi has an impressive 5,000 or so followers. Which key decision-makers in the financial community follow Sandra Navidi’s resonant analysis? Mitch Tan, a “girl with simple dreams,” who only ever retweets and from three accounts; Kathleen Culver, who has 13 tweets to her name; and Vanessa from “Midwest, USA” who has tweeted 17 times, but only says things like “2eme jour sur twiiter =D.” According to Status People, a web site that analyzes Twitter users, 96% of Ms. Navidi’s followers are fake, and another 3% are inactive. Only 1%, or 50, of her followers are really following her.

Scott Steinberg, rather like Santiago Swallow, is a “keynote speaker and bestselling futurist,” and also a “business management, technology and digital lifestyle expert.” He has more than 27,000 Twitter followers, including “Buy TW Followers,” “the world’s No. 1 Twitter followers seller,” and Meg McEachin, a young woman with two followers and no tweets whatsoever. As a digital expert, Steinberg may be surprised to learn that, according to Status People, 75% of his followers are fake and another 4% are inactive. Or maybe not: we can assume he knows his “bestselling” books, are not actually bestsellers — his “Modern Parent’s Guide To Kids And Video Games” ranks two millionth on Amazon’s sales list and his “Business Expert’s Guidebook” is three millionth. They are both published by “Tech Savvy Global”—whose CEO is Scott Steinberg.

Twitter faking is not only for would-be experts and speakers. Last year, the technology blog Kernel caught a CEO named Azeem Azhar purchasing 20,000 fake followers for his Twitter account. This was potentially awkward for Azhar, as his company, Peer Index, is —like his competitor Kred—in the business of measuring online influence and reputation. (Azhar told Kernel he did it to show how easily it could be done, and that such tactics didn’t affect Peer Index rankings.) A few months later, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney received national attention for gaining 117,000 new Twitter followers in a single day. More recently, Cuban dissident blogger Yoani Sanchez, who Foreign Policy dubs one the “10 Most Influential Latin American Intellectuals” and Time says is “One of the 100 Most Influential People in the World,” has also fallen under fake follower suspicion. Sanchez’s Twitter account has 475,000 followers, but according to Status People, 19% are fake and 41% are inactive. Although this still leaves her with 230,000 real followers, it also makes her vulnerable to doubters: in February, Mexican independent newspaper La Jornada used a detailed analysis of Sanchez’s Twitter account to raise the question “¿Quién está detrás de Yoani Sánchez?”—Who is behind Yoani Sanchez?

This is another way Twitter fakers do real harm. Just because you have fake Twitter followers, it does not mean you paid for them. Lady Gaga, Justin Bieber and Barack Obama have all made headlines for having fake Twitter followers—many millions of them. On average, only 28% of people following the 20 most popular Twitter accounts are real. The remaining users are either fake or dormant. According to Status People’s estimates, Justin Bieber has 15 million true followers, not the 38 million his Twitter profile shows, and Rihanna, not Lady Gaga, has the second highest number of users at 9.6 million, followed by Instagram—No. 12 in the official Twitter statistics—with 9.5 million.

People with large real Twitter followings, from celebrities to activists like Yoani Sanchez, are made to look guilty when they are in fact innocent. Fake followers created for sale to impostors like Santiago Swallow follow real users in an attempt to outwit Twitter’s generally very effective spam management systems. The more followers you have, the more likely it is that a fake follower will follow you. By trying to inflate themselves with the electronic equivalent of silicon implants, fakers make the system noisy for everyone.

But it seems to work: a few hours after Santiago was invented, Scott Steinberg proudly tweeted that he was “Thrilled to be giving keynote speech at Arizona Board of Nursing’s 2014 CNA Educators Retreat.” I know because Santiago Swallow retweeted it.

Follow Kevin @Kevin_Ashton. We welcome your comments at ideas@qz.com.