Shenzhen, China

Yekutiel Sherman couldn’t believe his eyes.

The Israeli entrepreneur had spent one year designing the product that would make him rich—a smartphone case that unfolds into a selfie stick. He had drawn up prototypes, secured some minimal funds from his family, and launched a crowdfunding campaign. He even shot a professional promo video, showing a couple taking the perfect selfie in front of the Eiffel Tower.

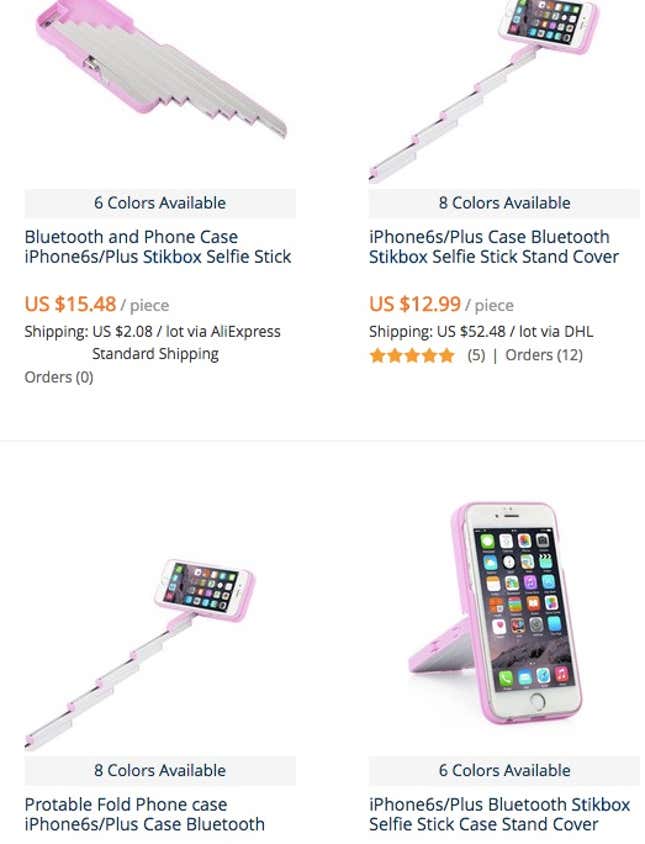

But one week after his product hit Kickstarter in December 2015, Sherman was shocked to see it for sale on AliExpress—Alibaba’s English-language wholesale site. Vendors across China were selling identical smartphone case selfie-sticks, using the same design Sherman came up with himself. Some of them were selling for as low as $10 a piece, well below Sherman’s expected retail price of £39 ($47.41). Amazingly, some of these vendors stole the name of Sherman’s product—Stikbox:

Sherman had become a victim of China’s lightning-fast copycats. Before he had even found a factory to make his new product, manufacturers in China had spied his idea online, and beaten him to the punch. When his Kickstarter backers caught on, they were furious. “You are charging double the price for what the copycats are charging, yet I seriously doubt the final product will be any better than the copycats,” one person commented.

Years ago, experts in the hardware industry would have had more sympathy for Sherman. Now, no one does—not even Sherman himself. While discussions of intellectual property in China’s manufacturing centers once focused on how brands and investors could protect their designs from China’s rapacious copycats, things have changed. Startups and foreign manufacturers are embracing a new reality—someone in China is going to make a knockoff of your unique invention, almost immediately. All any company or entrepreneur can do is prepare for it.

The origins of copycat culture

China’s knockoffs come in many different forms, and can affect businesses large and small.

In some cases, factories will make products that physically resemble ones made by prominent brands. Quality may vary—an Android phone with rounded edges and a stamped-on Apple logo will never come close to replicating the feel of an iPhone. But a counterfeit Gucci bag might easily pass for the real thing.

Sometimes, as was the case with Stikbox and the hoverboard, a factory or design team will spot a fledgling new product on the internet, figure out how it’s made, and start churning out near-identical products. Other times, a Chinese partner factory will produce extra units of a product they agreed to make for another company, and sell the surplus items themselves online or to other vendors.

Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, drew criticism when he told investors in June (paywall) that fake goods “are of better quality and of better price than the real names” and come from “exactly the same factories” as authentic goods. But there’s some truth to his comments.

Many analysts and historians have attributed Chinese counterfeiting to perceived aspects of Chinese culture like its emphasis on memorization in education, or an authoritarian government that stifles innovation. But rather than these reductions of culture, it has more to do with the evolution of China’s gadget and electronics manufacturing hub of Shenzhen, explains Silvia Lindtner, who researches Chinese entrepreneurship culture at the University of Michigan.

The city’s rise throughout the ’90s and early ’00s coincided with a boom in outsourcing among global multinational corporations. Instead of overseeing all the manufacturing of all the parts inside a product, large global hardware companies signed contracts with local manufacturers in Shenzhen to make and design products piecemeal. These contractors would then turn to smaller sub-contractors to help fill orders.

Many of the factories involved in these fragmented supply chains were small, family-owned entities operating without government approval. As they worked together, they realized they could do more than just supply parts that ended up in name-brand hardware. They could create rival products on their own, and reach customers who were too poor to buy a Nokia phone or Apple iPod, said Lindtner.

They banded together, at times sharing the recipes for specific electronic devices on online message boards. Thus began the shanzhai phenomenon, a word that literally means “mountain fortress,” but came to stand for products that skirt existing intellectual property laws. Phones and consumer electronics with names like “aPod” and “Nokla” flooded the market in the late ’00s.

Open-source manufacturing

The shanzhai era in consumer electronics gradually faded as incomes rose and brand-name smartphones became more affordable. But it enforced a culture of knowledge-sharing among manufacturers, wherein no single product design is sacred. Lindtner compares the culture of Shenzhen’s manufacturing ecosystem to the open-source movement among software developers. Much like how programmers will freely share code for others to improve upon, Shenzhen manufacturers now see hardware and product design as something that can be borrowed freely and altered. Success in business comes down to speed and execution, not necessarily originality.

“It’s understood that re-iterating or copying is part of the culture, and whoever is better and faster is going to make the deal,” said Lindtner.

Nowadays, China’s copycat phenomenon extends well beyond multinational corporations like Gucci or Nokia—startups are affected too. Thanks to the internet, factories and designers looking for the next hit product can easily turn to Kickstarter, Amazon, or Taobao to see what gadgets are hot. They message each other instantly using WeChat, China’s dominant chat app, or Alibaba’s chat software, which makes sourcing and assembly line planning even easier than in the pre-smartphone days.

“The whole Chinese system has developed around the idea that you have instantaneous communication and basically infinite information,” said Bunnie Huang, author of The Essential Guide to Electronics in Shenzhen. “Back in the ’80s people were talking about ‘just-in time’ manufacturing” as something to aspire to, he said. ”But now, the Chinese don’t even know any other way.”

Enforcement is impossible

Businesses can take certain legal precautions to reduce the risk of getting copied. A first, crucial step, according to Song Zhu, who litigates IP disputes between US and Chinese firms at California-based law firm Ruyak Cherian LLP, is to apply for utility and design patents for a product that’s valid in the US, China, and anywhere else one hopes to sell.

Entrepreneurs should also sign “NNN agreements” with potential Chinese partners before revealing any intellectual property. This contract prevents partner factories from using the intellectual property themselves after first view (“non-use”), sharing it with others (“non-disclosure”), or inking a partnership and then selling extra units on their own (“non-circumvention”).

But even with these protections, there’s no guarantee that you can stop someone from copycatting your product. Zhu said that the problem lies not in China’s courts, but enforcing rulings. Winning a case against one factory is relatively easy. But suing every factory and winning is expensive and time consuming.

“There are probably hundreds of small factories who might see a product on the internet and think ‘Hey I can do this,” said Zhu. “How are you going to shut down all of them? How can you even find out where they are? And the money you spend suing them is more than you can get out of the lawsuit.”

This is now the position Sherman finds himself in with Stikbox. While he hasn’t pursued legal action yet, he said he spends 20% of his time tracking down copycat factories through China’s giant e-commerce sites. It sometimes takes him up to five days to figure out one factory’s location.

“The copycat factory doesn’t show its address on Alibaba, only a trading company who represents them. Sometimes you have to track down two or three trading companies before you get to the actual factory,” he told Quartz.

Your great idea doesn’t matter

The spread of copycat manufacturing isn’t just creating headaches for hardware companies and startups. It’s challenging traditional notions of intellectual property—specifically, what type of ideas are valuable, and what type of ideas are not.

Decades ago, a company or entrepreneur might come up with an idea and then spend years securing the patents, completing the design, devising a manufacturing plan, and bringing it to market. Enforceable contracts with partners helped ensure these ideas wouldn’t leak to competitors—but so did the high cost of starting a factory, sourcing components, and managing assembly lines.

Moving the world’s manufacturing center to China makes the latter hurdles nearly disappear. Factories are set up in makeshift buildings. Cheap labor is abundant. Sourcing components is easy because of online marketplaces like Alibaba. As a result, smart ideas that are easy to turn into physical products become commoditized quickly.

Businesses are now forced to come to terms with this new reality. It’s not enough to create a product with a groundbreaking design or features, like a smartphone case that turns into a selfie stick. Companies dealing in the creation of physical goods now must make products that are impossible to copy exactly from the get go, by focusing on a special feature they can protect, or creating a coveted brand name consumers will pay more for.

“If you have a simple product that has some market demand, you will get copied,” said Benjamin Joffe, who works with hardware startups that are manufacturing in China at HAX, a venture capital fund. “The question is more, what do you actually have that’s defensible?”

Companies can defend themselves from copying by investing in software that complements physical hardware, and then guarding it. Apple, for example, does this with the iPhone, which carries the proprietary iOS operating system that’s unavailable on other phones. Or they can invest in well-crafted branding and marketing. GoPro, for example, has made a name for itself among its target user base of sports and photography enthusiasts. This can help insulate it from competition from Korea’s LG, Xiaomi, and small Chinese knockoff factories. (Sure, there are plenty of fake GoPros out there, but some consumers will pay more for the real thing.)

Alternatively, a company can make a product that requires sophisticated manufacturing know-how, so that the average factory wouldn’t bother trying to copy it.

Hong Kong-based startup Native Union, for example, created an earpiece for smartphones that looks like an old-fashioned, crescent-shaped landline phone receiver. It was clever, but got copied immediately. Founder Igor Duc later changed the company’s direction and began making a totally different product—smartphone cases made out of Italian marble that sell for $80 each. They’re more difficult to make than the average consumer electronic device, which prevents copycats from surfacing.

“When you use complicated raw materials like marble you need to have a lot of expertise about what is good quality, and you need to shave it with a very specific machine,” said Duc. “Whereas a plastic injection is easy to copy, what we do now is more complex.”

The bright side of copycats

Joffe, the venture capital investor, argues that some companies might even benefit from copycatting, as it can bring more awareness to the product itself. “If you have more customers buying the fake product then it creates more awareness for the real product, and it becomes an aspirational thing. At some point they might be able to afford the real thing.”

This is what Sherman reminds himself of, as he scrambles to fulfil orders while his empty-handed Kickstarter backers ponder buying a fake from Taobao instead.

“There are other selfie stick cases but we are the only ones that have been copied. So it shows that our product is worth being copied,” he said. “The quote that comes to mind is, ‘Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.’”

Yet Sherman estimates that he has lost “hundreds of thousands” of dollars in potential revenue due to copycats. Imitation isn’t just a sincere form of flattery, it’s an expensive one as well.