Self-balancing scooters—commonly known in the US as “hoverboards”—have entered the pop culture zeitgeist this year, and retailers are rushing to restock the shelves in time for Christmas. Justin Bieber is riding one and they’re one of the most-wanted sports items on Amazon.

But hoverboards are getting attention for another reason—they keep exploding.

Over the past several months, local fire departments in the US and UK have reported incidents involving hoverboards catching fire. Families in Alabama, Louisiana, Florida, Hong Kong, and London have seen their houses burn after the boards burst into flames during charging. On Oct. 21, the London Fire Brigade warned that owners should keep an eye on boards while they are charging, after being called to two fires in two weeks started by “personal transporters.”

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

“The reporting on accidents does not put things into perspective, statistically,” says Benjamin Joffe of Hax, a hardware investment company in Shenzhen. “Considering the lack of standards, controls, and traceability, the question is not ‘Why have there been so many accidents?’ but rather, ‘Why have there been so few?”

Of 17,000 hoverboards inspected by the UK’s National Trading Standards since October, 15,000, or 88%, are “unsafe,” because of “issues with the plug, cabling, charger, battery, or the cut-off switch within the board, which often fails,” the standards agency said Dec. 3.

Nearly all of these two-wheeled, battery-powered toys are made in China, many in the cheap tech manufacturing hub of Shenzhen. Already millions of hoverboards have been shipped out of China this year—in October alone, 400,000 shipped from Shenzhen (link in Chinese).

How did this relatively new product manage to flood overseas markets so quickly, despite serious safety problems? The answer offers a case study in the pros and cons of China’s stunningly efficient manufacturing sector, in which a totally new product can go from blueprints to store shelves in weeks.

Untangling the reasons behind the safety problem leads to the hoverboard’s murky provenance, Chinese factories’ growing skill at tapping export markets quickly, and the “self-regulated” nature of the consumer electronics market, particularly in the US.

A fad hits during patent wars

The hoverboard’s spike in popularity happened just as the early manufacturers became entangled in a patent war.

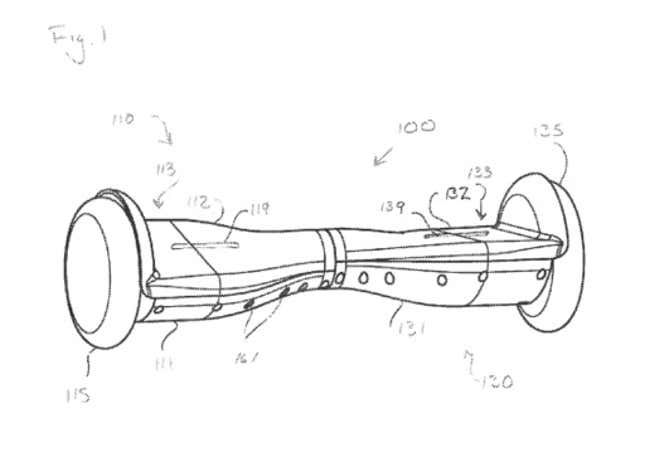

The man at the center of the legal kerfuffle is Shane Chen, a Seattle engineer who was issued a patent in 2014 for a two-wheeled, self-balancing vehicle controlled using foot-motions over a connecting board:

Chen introduced the device during the January 2015 Toy Fair, a major annual trade show in New York City. There he rolled over (on his hoverboard, of course) to a booth occupied by IO Hawk, an American distributor of identical devices made by China’s Hangzhou Chic Intelligent Technology, better known as CHIC. CHIC is a ”white-label” manufacturer (it makes products for companies to re-sell under their own names) that specializes in knockoffs of Segway vehicles. These essentially use the same underlying technology as the hoverboard, relying on gyroscopes to detect a user’s balance.

In June, Chen sued IO Hawk in the US and CHIC in China for allegedly infringing on his patents. Then, in September, Chen himself was sued by Ninebot (pdf)—the Chinese acquirer of the Segway, which believes it holds the underlying patent for all such self-balancing vehicles in the US, described (pdf, pg 3) as “a personal transporter with a balance monitor and a method for using such a transporter.”

The three-way dispute over the product’s intellectual property status has effectively turned the manufacture of the hoverboard into a free-for-all, as importers in the US and elsewhere rush to profit from the lack of legal clarity.

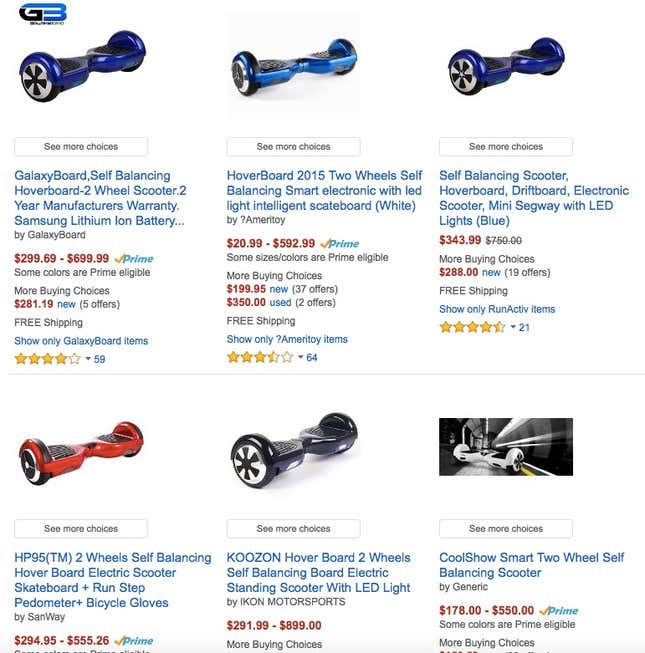

Hundreds of makeshift entrepreneurs, many of whom have no engineering or technology expertise, are doing deals with white-label Chinese manufacturers to make hoverboards. They then re-sell them using names like Phunkeeduck, Swagway, Fiturbo, Hover Booster, Galaxy Board, and Cyboard. Just six months after Justin Bieber was caught showing off his IO hawk in Hollywood (video), millions of hoverboards are now appearing on retail shelves.

Manufacturing in China is easier than ever

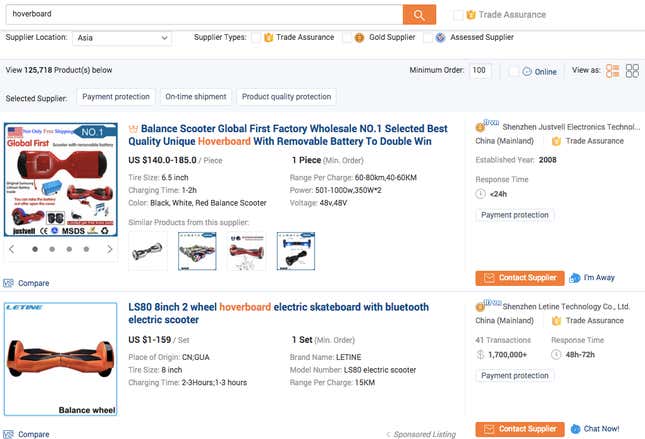

Thanks to Chinese e-commerce giants like Alibaba, placing a bulk order to get a product manufactured in China is easier than it has ever been in history. Through Alibaba.com, which lets wholesalers purchase bulk orders of almost anything, absolutely anyone can order ready-made hoverboards, priced as low as $130, from a manufacturer or trader in China. These wholesale boards can be branded with whatever name the buyer chooses, then shipped to destinations all over the world.

Alibaba will even loan US small businesses as much as $300,000 to place an order for made-in-China goods.

That explains the deluge of identical-looking hoverboards on Amazon and at other retailers. While many have unique brand names and tiny differences in detailing, the vehicles are nearly identical. In some cases they are just that—manufactured by CHIC or another Chinese company, and branded especially for an importer.

None of these hoverboards sold in the US are subject to any safety or quality requirements or official inspections. (The UK has much more strict mandatory safety standards, but apparently faulty products are still getting in.)

With few barriers to importing and selling them in the US, devil-may-care distributors are snapping them up.

“All the hoverboards in the US are sold by importers, who barely even know the factories they are buying it from,” Andrew “Bunnie” Huang, a hardware analyst based in Singapore, told Quartz. “In a hyper-competitive market that’s driven by a fad, taking six months to do a comprehensive testing program for safety means you’re missing out on a lot of business,” he adds.

The lithium battery question

Many of the hoverboard fires have happened while they were re-charging their batteries. The results of investigations have yet to be made public, but there are two possible culprits. The boards may have exploded due to lithium ion batteries overheating thanks to an electrical short, or a mismatch between the voltage of the charger and the voltage of the battery.

Fires have been caused by lithium ion batteries for years. In the early 2000’s, Dell and Apple issued recalls after their laptops burst aflame after overheating. Japan Airlines suffered a near-fatal accident when one of its Boeing carriers started smoking due to a faulty lithium ion battery.

Hoverboard lithium ion batteries are bigger than your average consumer electric product, and take voltages of about 36V. That’s more than three times larger than the battery inside a MacBook Pro, which tend to be about 7 to 10V. (A Tesla Model S, on the other hand, has a 375V battery.)

Manufacturers can take precautions to ensure that battery-charged products don’t overheat and catch fire. UL is a private, for-profit company that certifies electronics as safe in the US, and has standards that cover all types of batteries and chargers intended for household charging. Many big retailers in the US, like Walmart, will only sell electronics that have received a UL certification.

Nonetheless, UL engineer John Dregenberger told Quartz no hoverboard company has ever passed any of UL’s tests. He would not specify whether any hoverboard maker or importer had actually applied to receive UL certification, citing company policy on not commenting on specific brands.

Many hoverboards say on their websites that they contain Samsung lithium ion batteries, which have been independently certified as safe by UL, but there’s no guarantee all their parts are checked by UL. And it is remarkably easy for manufacturers to fool distributors about the validity of the product’s parts, one prominent manufacturer said.

“There are some factories right now that will say they use Samsung batteries but don’t,” an international sales manager from CHIC told Quartz. “They wrap a piece of paper around the battery that says ‘Samsung’ when it’s not Samsung.”

Greedy importers

It would be easy to blame hoverboard’s safety problems on Chinese manufacturers—but industry experts say importers share at least as much of the blame.

In Shenzhen, China’s consumer electronics hub, hundreds of factories crank out components that become iPhones, televisions, laptops, smart watches, and any type of gadget imaginable. An estimated 90% of the world’s electronics originate there.

The city’s ecosystem makes manufacturing extremely efficient, but large factories with reliable reputations sometimes order from several component suppliers, who then might outsource that order to other suppliers. Shenzhen specializes in “building what people want, at a price that people want to pay,” says Joffe of Hax, the hardware venture capital firm in Shenzen. “Under pressure of retailers and competition, some factories certainly cut corners in testing.”

But importers should be responsible for enforcing quality safety standards, Joffe and others say. That’s because when an importer places an order with a Chinese manufacturer, they dictate the standards a product is required to meet—not the other way around.

“Chinese manufacturers operate according to a ‘make to order approach,'” Fredrik Gronkvist, a consultant who helps foreign vendors source products from China, told Quartz. “If you fail to communicate the regulations to which a product must be compliant, it will not be.”

Some importers have apparently taken a hands-off approach to ensuring safety standards are met. Quartz reached out to Beyond Limits Corporation, a New Jersey-based pillow importer that began selling “Galaxy Board” hoverboards in October. When asked about UL certification, Dino Bougdanos, who has an “executive leadership” role at Beyond Limits, said he wasn’t familiar with it. “That’s typically taken care of by our partners,” he told Quartz. The Galaxy Board is currently listed on Amazon.

Accidents have happened even when hoverboard importers claim they are following local safety standards. Swagway, one of the better known importers, claims that it uses UL-certified Samsung lithium ion batteries on its FAQ page, as well as several other certifications. But just two days ago, a Swagway reportedly caught fire in a Westchester home. Swagway did not respond to an emailed request for comment from Quartz regarding the incident.

US regulation is lax

The US regulator, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), has “mandatory compliance standards” for many products that consumers buy. But the agency relies on importers and manufacturers to test products themselves, and show in writing they are certified.

CPSC standards cover toys, clothes, and flammables, and the CPSC will inspect products in these categories when they hit ports. But shipments of products outside these categories, like hoverboards, are often not inspected as they make their way towards shelves, the agency told Quartz. And their sale remains perfectly legal.

“We are a small agency. We have a couple dozen employees that are co-located at the port, so we have to be very targeted, very smart with the products that we are looking to detain,” Scott Wolfson, adviser to the chairman at CPSC, said.

Instead, items like hoverboards depend almost entirely on “voluntary,” self-regulated safety standards by third-parties (like UL, which is a for-profit company). While big box retail companies are not required to sell only “UL-certified” electronics, they often will only stock items that do.

The UK is relatively strict by comparison. Certain products, like toys with mechanical or electrical components, or household electronics, must be certified CE—a certification similar to UL. While it’s not uncommon for non-CE certified products to pass through customs, it is illegal to import and resell such goods.

Will the industry step up?

Sean Kane of Safety Research and Strategies, an organization that studies safety policy, believes that the industry itself must organize to form a standard that covers all aspects of a self-propelling, electric vehicle, and incorporates advice from UL, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, and other groups.

“If you had a general category for standard for personal mobility devices that incorporated these existing standards, you would have the ability to point to a hoverboard and know if it were completely safe or not,” he said.

Given how new and fragmented the industry is, it is hard to see that happening right now. Recently, another player has stepped in—scooter-maker Razor recently paid Shane Chen, the patent-holder, for the rights to his patent. Can Razor fend off other patent-holders, stamp out copycats, and come up with specifications or a hoverboard that doesn’t catch on fire? That remains to be seen.

For now, consumers are left shouldering the dangers of buying a hoverboard.

Echo Huang contributed reporting.