Sophisticated satellites cost hundreds of millions of dollars and are assembled in clean rooms by technicians in full bodysuits. And then, to fly them into space, we strap them onto enormous rockets that explode spectacularly once in every 20 takeoff attempts.

Who’s on the hook when things go wrong? Welcome to the volatile world of space insurance.

When a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket burst into flames Sept. 1 during a pre-flight mishap, the satellite sitting on top was the more valuable casualty. AMOS-6, owned by the Israeli company Spacecom and manufactured at a cost of $175 million, lay at the center of a delicate web of global contracts between its operator, the operator’s potential acquirer, its transporter, its manufacturer, and their various clients, including Facebook and NASA.

The answer to who would pay for the loss came a few days later, when the company that built AMOS-6, state-owned Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI), said it believed the loss was covered under the “All Risks Pre Launch policy” for events “during transit and whilst at the launch site” it had purchased from, naturally, Lloyd’s of London.

The fact that it took days is a testament to the technicalities involved in such complicated insurance and the secrecy of the rocket business. But it’s also a sign that the market for such an unstable financial instrument might not be ready for a coming increase in commercial satellite launches. (Governments, which still launch the most satellites, by and large do not bother insuring them.)

But perhaps satellite insurance is exactly what return-hungry insurers need, in an economic environment where high risk and the yields that accompany it are hard to find.

Got risk?

Rocketry has plenty of risk. The job is simply moving a couple of tons a few hundred miles, but going straight up requires using forces so strong that they are typically used only by the military, and only when mass destruction is on the table. Last week’s Falcon 9 fire provides a good illustration: As you watch all this propellant ignite, keep in mind that the machine being destroyed is designed to control and channel that force during normal operation.

Usually, an insurance business is built on high volume, low value, and predictability. Life insurance, for example, relies on large numbers of people paying small sums over time and dying within a fairly standard age range.

“Space is the exact opposite. You have twenty commercially-insured launches a year, that’s it. Worldwide, it’s basically a catastrophe business,” Mark Quinn, now CEO of global insurance broker Willis’ space division, told Quartz last year. “You’re looking at one loss that can give you a hit of $400 million, and annual market premium is $750 million. One loss that burns more than 50% of the annual income for the entire market.”

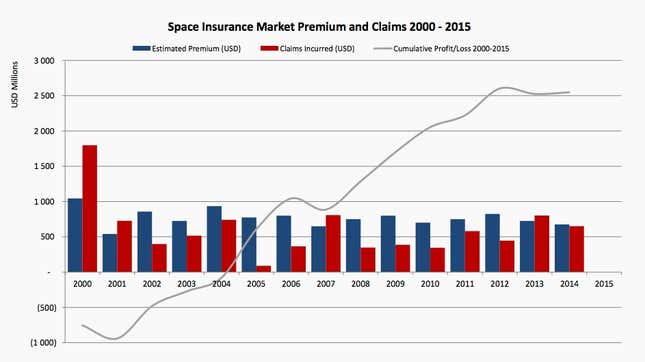

Indeed, in 2013, the market hit the red after $775 million in premiums were outstripped by more than $800 million in claims, according to industry data. That year, among other failures, a Russian Proton rocket carrying three navigation satellites exploded when its guidance sensors were installed upside down, and a youthful rocket company called Sea Launch put an Intelsat communications satellite right into the Pacific.

The industry saw another weak year in 2014, paying out about $650 million in claims on $700 million in premiums, according to Willis records. A disastrous 2000 wiped out profits for years.

But where there are risks, there are great rewards: From 2008 to 2012, space insurance premiums easily overtopped losses; in 2008, industry revenue hit a net of $600 million after payouts.

What are we insuring?

Rockets are designed as use-and-discard items (though SpaceX and Blue Origin are pushing to make them reusable). The satellite is what actually gets insured.

“We don’t insure our launches, nobody in the rocket business does, except for damage on the ground,” SpaceX CEO Elon Musk said last year after a Falcon 9 carrying cargo to the International Space Station exploded.

But satellites cost millions of dollars—think of them as a multi-ton flying server farms welded into a collection of powerful transmitters—and have millions of dollars more riding on them, in term of contracts obligations.

Assets like that demand financial protection, and satellite operators typically buy two products: Launch insurance, which covers the satellite from when the rocket ignites for launch until it is safely in orbit, and orbital insurance, to cover the failure of the satellite when it is doing its job in space—and more satellites are lost during their first year in space than during launch mishaps. If your satellite TV network goes down during the World Cup, someone has to pay.

But even so, most satellite operators don’t buy insurance. As of 2013, only 212 orbiting satellites were insured, out of 1,300 currently active satellites.

Notice that neither launch or orbital insurance applies to bad things that happen to a satellite before lift-off, which is why in the initial aftermath of the Sept, 1 explosion, many worried that AMOS-6 would be a total loss. Often, the satellite is not mounted on the rocket during pre-flight engine testing, but in the last year SpaceX has begun doing it more often to save time as it attempts to launch a rocket once every two weeks. (Carefully raising and lowering the 70-meter-tall rocket is a time-consuming process.)

IAI is convinced that its insurance will cover the loss of the satellite and allow it to reimburse Spacecom. The latter firm had reportedly lined up a $285 million policy to cover the satellite during and after launch. Industry sources say that SpaceX will return either $50 million or a free launch to SpaceCom. “We don’t disclose contract or insurance terms,” a SpaceX spokesperson told Quartz.

The heat is on

Last week’s explosion has caused great consternation in the space industry. It’s rare for something to go dramatically wrong before the rocket’s engines are ignited; the last time, according to space historians, was in 1959. Until SpaceX can convincingly isolate and cure the problem, there will be uncertainty for commercial satellite operators, many of whom are relying on SpaceX to fly their birds and will face year-long waits for service from one of its competitors.

And that may mean premiums are headed back up after hitting recent lows, potentially putting a crimp in SpaceX’s business if its clients see increases in insurance costs down the line.

“Insurance goes in cycles—highly profitable, rates down; lots of losses, rates up—and we’re in a long, soft market trough right now,” Quinn said last year; insurers eager to gain business had written policies with low premiums for reliable technology. But more losses could lead to pressure from management to recoup costs through higher premiums.

The space industry hit something of a turning point after SpaceX introduced cost competition into the business with its Falcon 9 rocket in 2010. It forced competitors to lower prices, creating opportunities for new businesses in orbit that leverage some of SpaceX’s advantages—new technology and a Silicon Valley-style willingness to experiment.

The potential growth in the satellite business has brought new insurers to the table. Today, more than forty companies provide different kinds of space coverage, often in consortiums. This has led to record-low premium rates for the reliable-if-pricy European Ariane rocket and proven satellite platforms. In recent years, Russia’s somewhat failure-prone Proton rockets have been a major source of revenue, providing a third of industry premiums in 2014.

If you count the engine test as a mission failure—and it is debatable, since it didn’t happen during a mission—SpaceX’s Falcon 9 now has a comparable success rate to the Proton.

The next cycle

SpaceX, despite its relatively new rocket, had managed to obtain reasonable rates thanks to positive publicity and by being transparent about its technology. The company’s long-term partnership with NASA helps convince clients and their insurers that SpaceX can be trusted with their technology and money.

But after last year’s mission failure and this pre-launch accident, underwriters for SpaceX’s clients may demand a higher price to cover their satellites during launch. Any hikes probably won’t hurt SpaceX’s ability to deliver the cheapest launches on the market, but it will be an extra hassle, especially as it looks to fly commercial clients on its forthcoming Falcon Heavy rocket.

And the test fire certainly won’t help with the company’s most ambitious project, developing reusable rockets to replace the one-use versions currently in use, that are typically discarded after they deposit their cargo in space. The company thinks it can cut a further 30% in costs if it can reuse the first stage of the Falcon 9 rocket, and it has recovered six so far from successful missions.

Just last week, SES, the European satellite giant, announced that it would launch a new communications satellite on the debut flight of a reused Falcon 9 rocket. But the recent accident could complicate efforts to insure cargo flying for the first time on a used rocket, even more so than on new Falcon 9s.

“What you are underwriting is the performance of hardware; you’ve got a rocket flown 50 times successfully, that’s got a great rate,” Quinn told Quartz. “The hardest things to insure are first flight items, things that have never flown before.”

Even harder, SpaceX and its clients may find, will be insuring something that has flown before.