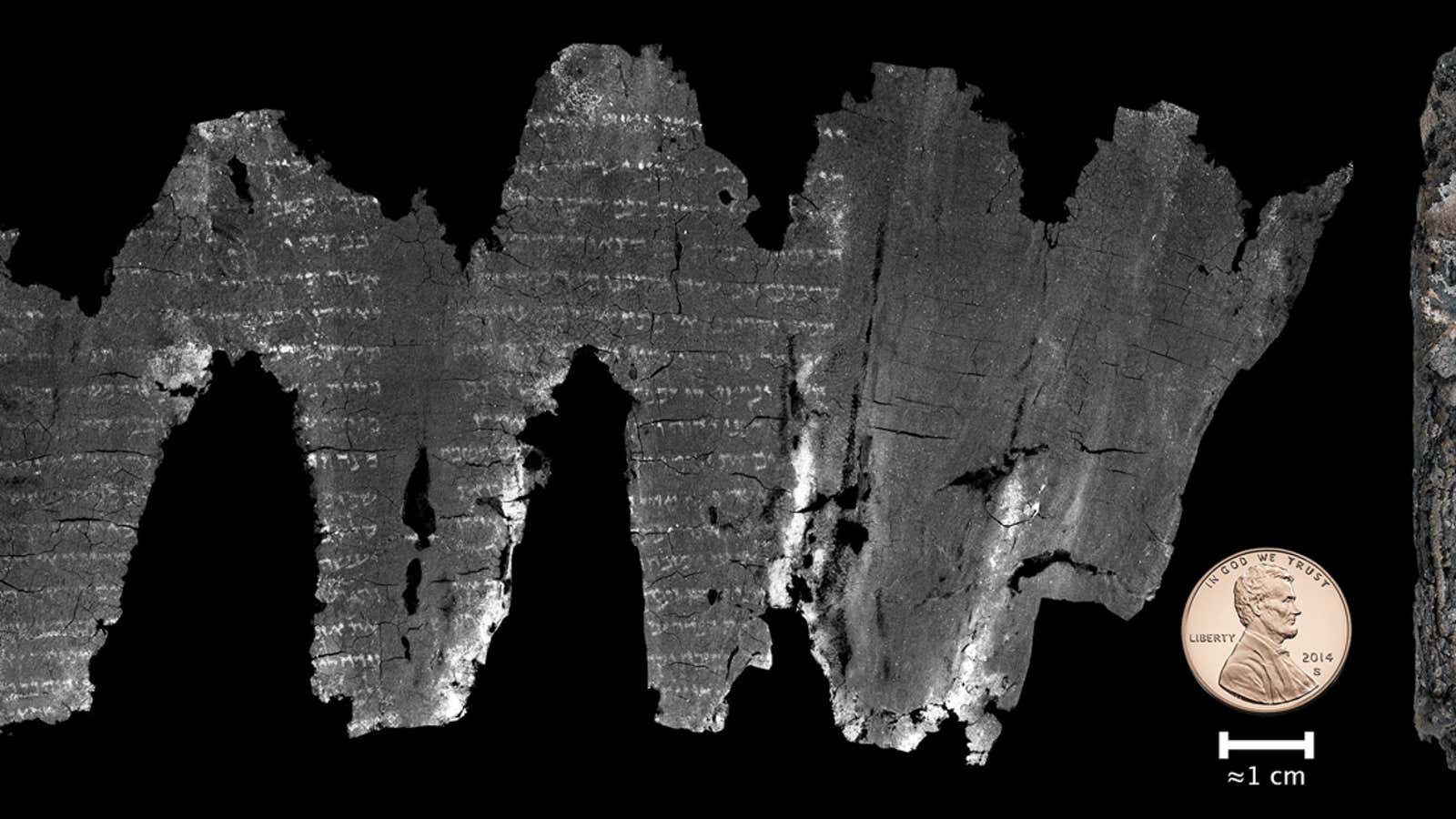

For nearly 50 years, a charred ancient parchment, discovered at the archaeological site En-Gedi in Israel, has remained unreadable. The damaged scroll, written on animal skin, was too fragile to unravel; efforts to read it led to pages disintegrating on contact.

Now researchers have virtually unrolled the scroll using imaging technology called X-ray microtomography, and it turns out that the En-Gedi document is the oldest known copy of the Hebrew Bible in the Masoretic text—the authoritative text used in Rabbinic Judaism and Protestant bibles. The famous Dead Sea Scrolls, while older than the En-Gedi bible, have many differences from the Masoretic text.

The exact age of the En-Gedi bible is still up for debate. Paleographical research indicates that it was likely written in the first or second century CE, while radiocarbon results date the scroll to the third or fourth century CE. Either way, “the En-Gedi scroll…offers a glimpse into the earliest stages of almost 800 years of near silence in the history of the biblical text,” the researchers wrote in a study published in Science Advances on Sept. 21,

Perhaps even more important than this specific discovery is that the findings prove a method that could be invaluable for the field of archeology: the En-Gedi bible is the “first severely damaged, ink-based scroll to be unrolled and identified noninvasively,” according to the study.

A team of computational scientists and archaeologist from the University of Kentucky in the US, Hebrew University in Israel, and the Israel Antiquities Authority first X-rayed the untouchable document to create digital slices of the scroll that could then be separated like pages, and viewed on computer. The process is complex, starting with imaging the scroll in its entirety and creating a three-dimensional volumetric scan, then segmenting, flattening, and texturing those images. The result is a set of two-dimensional images that reveal the writing on the original scroll.

The virtual discovery offers hope for the restoration of damaged historical texts currently preserved in archives all over the world that have yet to be studied. The En-Gedi scroll researchers believe their virtual reconstruction technique is a major development in the field of manuscript recovery, conservation, and analysis.

They’re not alone; University of Mississippi scholar Gregory Heyworth was so taken with the possibilities of reading ancient texts with futuristic tech that he shifted his professional focus from medieval scholarship to text science and the reconstruction of ancient works. Heyworth now directs the Lazarus Project, a nonprofit that restores damaged and illegible manuscripts and maps with spectral imaging technology.

He gave a TED talk in October 2015 explaining why we need text extraction that can be done without physically handling fragile artifacts: ”Imagine what unknown classics we would discover, which would rewrite the canons of literature, history, philosophy, music—or, more provocatively, that could rewrite our cultural identities, building new bridges between people and culture.”