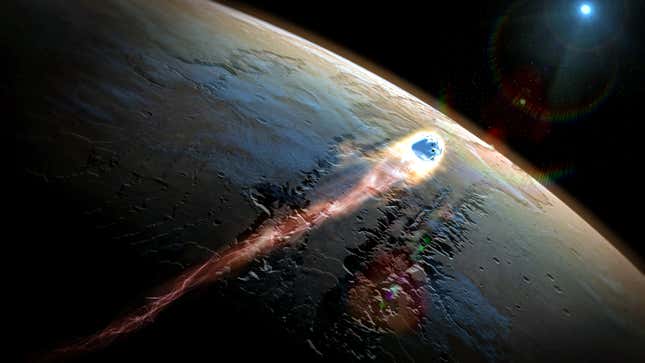

SpaceX is a company built to go to Mars, but are those ambitions getting in the way of its ability to achieve them?

In a few days, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk will unveil his plans to explore Mars at a global space conference in Mexico. The event has been widely anticipated by fans of the billionaire entrepreneur and SpaceX. But an enormous fire that consumed a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket during a pre-flight test on Sept. 1 has dampened the positive mood.

Now, critics are asking if SpaceX is taking on too much, too fast. The company has become known for injecting a Silicon Valley-style willingness to break conventions and learn from failure into the staid aerospace industry. SpaceX’s culture is the secret sauce that led it to become the first private company to design and fly its own orbital rocket, in the process disrupting the space launch business with the cheapest flights around.

But the brash company has attracted its share of detractors. Musk had not been shy in observing the bloated budgets and lack of innovation at his corporate rivals. When his company has hit stumbling blocks—like the recent fire or the explosion of a mission to re-supply the International Space Station (ISS) in 2015—they have not been shy about questioning whether SpaceX is reliable enough to be trusted when hundreds of millions of dollars hang in the balance.

Some, including anonymous officials at NASA, are suggesting that the company’s primary businesses—operating a commercial launch service, including critical missions to re-supply ISS, and developing a next-generation manned spacecraft for NASA—are suffering because the company’s workforce is distracted by projects like a new heavy rocket, satellite systems and of course plans to send unmanned probes to Mars sometime after 2018 and follow it with an “interplanetary transport system.”

In their view, discussing interplanetary space exploration while the more prosaic task of operating an orbital taxi service to the ISS falls behind schedule requires care typically reserved for rocket propellant.

United Launch Alliance, the joint venture of Boeing and Lockheed Martin that is SpaceX’s primary competitor in the rocket business, called out SpaceX during this week’s Air Force bidding contest to launch GPS satellites. They complained that a recently opened bidding process—a change forced by SpaceX—isn’t focusing enough on reliability, despite the Air Force’s position that its certification process forced SpaceX to meet a “high technical bar” for operational success.

“As recent launch failures have shown, rockets are not commodities,” ULA said in a statement. “They are high-risk systems and the consequences of failure are costly and far-reaching.”

Fail fast

“Twenty years ago, cell phones existed, [but since then] the tech has gotten better, and the price has gone way down,” says Brian Bjelde, SpaceX employee #14, and now the rare engineer turned head of human resources. “Why is launch technology not the same?”

This is the question that led Musk to found SpaceX in 2002, when even with hundreds of millions of dollars at his disposal, he couldn’t find a cheap way to send a greenhouse to Mars. In response, he founded a company designed to jettison what he saw as the bureaucracy and bad incentives of the aerospace industry, embrace modern manufacturing techniques, and perhaps most importantly, bet that investments in cheaper, reusable rockets would be rewarded with a growing private market.

“Elon comes from Silicon Valley, he is cut from that cloth, and he subscribes to the model where you want to fail early and fail often, get the gremlins out of the system, and get to the final product, the safest, most reliable product, as soon as possible,” Bjelde says.

Part of that cloth is the idea of a company that’s bigger than simply earning a buck. At the heart of SpaceX is the goal of making space travel so cheap that humanity could be a multi-planetary species. It’s a management strategy the venture capitalist Marc Andreessen identifies as vital to recruiting and motivating the best employees, one shared by Google, Facebook and (once) Apple. It’s not a surprise that Musk and fellow Silicon Valley space entrepreneur Jeff Bezos have framed their companies as more than mere rocket factories.

SpaceX leadership’s included aerospace veterans like president Gwynne Shotwell, launch executive Tim Buzza (now with Virgin Galactic), and top engineer Hans Koenigsmann. But the rank-and-file is heavily salted with talented young engineers, some fresh out of graduate school or college, eager to make their mark and not interested in ”integrating other people’s technologies,” as Scott Nolan, an early employee, puts it.

“I would say the culture of SpaceX is a kind of ‘do the impossible; if it isn’t possible, you’ll find out,'” says Stephanie Xenos, a former SpaceX engineer who managed missions including a crucial test of its Dragon 2 space capsule. “I don’t think there’s any way SpaceX could accomplish what SpaceX did without having that culture. You don’t want to slack off, spend your day on Facebook, you respect your peers and you want to contribute.”

Employees bought into the culture, according to Erin Beck Acain, who spent six years at SpaceX in a variety of technical roles. She notes that it may seem corny, but the company’s mission statement—”fast, cheap, and reliable”—actually mattered.

“Most people keep a copy of that at their desk,” she says.

That culture—and hundreds of millions in development funding from NASA—allowed the company to debut the Falcon 9 orbital rocket at a cost of at least $70 million less than its competitors, quickly taking business away from rivals. The confidence it gained won the company its largest contract yet in 2014, $2.6 billion from NASA as part of a race with Boeing to build a new manned spacecraft that would replace the Space Shuttle.

Stop Failing

Now the company moved from its singular early focus—designing a functioning orbital rocket and cargo capsule—to producing them at a much higher rate while developing new technology in other areas. In 2014, the company had six successful launches; the next year, by June, it had matched that number and planned to go for 12.

Then, during the company’s 19th Falcon 9 flight, a faulty strut restraining a helium bottle inside the rocket’s oxygen storage tanks snapped, sending the bottle shooting to the top of the tank and leading to the explosion that destroyed the rocket. The June 2015 explosion—or anomaly, as SpaceX refers to the issue—grounded SpaceX, costing it hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue.

“All of the projects I was working on, everything just kind of stopped,” Xenos said. ”Everyone was reviewing data.”

It took just six months for SpaceX to diagnose the problem with the strut, built by a subcontractor, and return to flight, which it did successfully in December 2015, launching a commercial satellite from Cape Canaveral. It flew nine more times before last month’s fire. That’s far faster than the nine to 12 months it usually takes to diagnose and eliminate a problem following an incident like that. Another rocket company, Orbital ATK, plans to fly its Antares rocket in October for the first time since a mission failure two years ago.

SpaceX says it hopes to return to flight after its most recent explosion by November.

Both failures have caused agita at NASA, SpaceX’s biggest client and earliest institutional backer. The US space agency has bet heavily on the company to deliver a cheap manned spaceflight solution that will end US reliance on Russia to access ISS and free up more money in its science budget. But both Boeing and SpaceX are slipping behind schedule, due to funding delays and technical challenges alike.

After the failed mission to ISS in 2015, NASA reprimanded the company, “expressing concerns about the company’s systems engineering and management practices” in a letter, after its investigation suggested that human error, even workers standing on the strut that broke, could be part of the problem.

SpaceX denied that this was a problem, with a spokesperson telling Quartz that “the FAA voted and approved the material flaw to be the most probable root cause. Not somebody standing on the strut.” But recognizing the importance of its largest client, the company bent over backwards to maintain its confidence, including a reorganization that created new teams led by top executives and focused on reliability.

“It’s a growth thing,” Bjelde says. “When you’re a small team and you’re in the garage shop, it’s easy to have that awareness. When you’re building lots of technical hardware at a good clip, it behooves you to have these added layers. It’s not necessarily an added hierarchical layer, it’s an investment in reliability. “

How hard is too hard?

Scott Pace, a former NASA official, said that any company attempting to do as much as SpaceX needed to carefully assess whether it was pushing its workers too hard.

“It would be ambitious for any company to do a schedule like that,” Pace says. “When you look at changes in launch schedule that are increasing over historical norms, you should be worried whether or not schedule pressure is putting unacceptable strains on the workforce.”

SpaceX rejects out of hand the idea that it is pushing its workers too hard. Bjelde shared an internal survey with Quartz that showed most workers reporting a 50- to 57-hour work week, and noted that getting to Mars is a long-term proposition which requires a sustainable workforce. Employees say the company’s hard-driving reputation is a legacy of the company’s start-up DNA and the enthusiasm of its employees, but Bjelde maintains the company is focused on work-life balance now.

“I remember burning the midnight oil with Elon,” Bjelde says. “Come 11 pm we’d all hop off and play Quake III Arena for a couple hours to burn off some steam, but those days are behind us.”

Current and former employees tell Quartz that the environment is not unlike that of any high-performance workplace where employees are passionate about what their work. ”Day to day, the Mars culture is not one that interferes with your work,” Xenos says.

It’s also an environment, they say, where workers with concerns could quickly get in touch with upper management. Shotwell, the company’s president, maintains a system to register anonymous complaints from employees.

“Elon would always send out e-mails before the launch, ‘Please take the time, take a break and re-review all of your paperwork, all of your data,’ and everybody took that really seriously,” Xenos said.

Growing pains

Still, beyond the tacit admission of a need for improved systems in the reorganization, there were other hiccups in SpaceX’s expansion to the 5,000 person company it is today.

The company is in the process of settling a class-action lawsuit with a group of employees who complained that the company pressured them to work through lunch breaks and rest periods. These cases are common under California labor law, and one former employee told Quartz that the company’s willingness to let even salaried workers operate at their own pace conflicted with California’s rigid time requirements.

“Our company has in place and enforces strong policies that ensure compliance with all California labor and employment laws, including those at issue in these actions,” a SpaceX spokesperson says of the case. “However, given the expense, burden and uncertainty of continuing litigation, we elected to settle this matter so that we can continue to focus on our business.”

Another suit might give more pause: A former employee who inspected parts from outside manufacturers says he was wrongly fired after complaining that his supervisors would not give him time to use a computer, rather than hand tools, to verify each part was up to specifications, a practice his attorneys say was “misleading to the customer and created a high risk of accidents.”

“SpaceX denies the claims and will vigorously defend itself in court,” the company tells Quartz. A person familiar with the litigation said that there was little difference between the two inspection methods, except the computerized system was only efficiently used when high-volumes of parts were arriving.

The tension of success

SpaceX has yet to diagnose the specific flaw that led to the recent fire. Its latest update pointed to a problem in the helium coolant system that chills the liquid oxygen stored in the second stage of the Falcon 9 rocket, but said it was unrelated to the problem that occurred in 2015.

“In a weird, bittersweet way, we need to embrace these anomalies,” Bjelde says. “[Every] time we have one, we end up a better company because of them, we root out some gremlin in our operations. The people that will fly our hardware next will have a better vehicle and a better, more reliable launch because of it.”

This spirit of iteration is behind SpaceX’s most impressive accomplishment to date: Landing the first stage of six different Falcon 9 rockets that carried satellites to orbit or cargo to ISSS. Most rockets are discarded, and no government or company had ever created the technology to return rockets to earth. Besides being quite a show, the reusable stages are expected to further cut the costs of launch. And they also develop the tools the company will need to land on Mars.

“Elon keeps a short list, usually it’s five bullet points, these are things that we are working on right now, as our big overall company goal,” says Acain. “You might have a project within that, and it might not seem related, but I bet you it is.”

This ability to package innovation and execution together is the promise of SpaceX, since traditionally the two values are in tension. It’s why many in the aerospace community are concerned since the fast-fire in August, and why many haven’t lost faith.

“I think there is evidence of something special in SpaceX, something we haven’t seen evidence of in other companies,” says Andrew Gray, the head of the Game Changing Technology Development office at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “It’s a company that is taking calculated risks for maximum gain. You and I don’t do that—billionaires do that. Elon has empowered his people at the company to act like him.”

The real question may not be whether Mars is a distraction for SpaceX, but if the company can find a way to recoup the cost of its investments in the Red Planet. Its various businesses, including a mooted satellite internet network, are designed to generate profits to be put toward Mars. But it’s the costs of such a mission would still exceed what SpaceX can fund from its own profits, analysts say, which means a full-fledged mission will require deeper cooperation with NASA even as officials worry about whether Musk shares their priorities.

Still, NASA administrator Charles Bolden gave SpaceX a vote of confidence today, praising their ambition.

“Entrepreneurs are able to look at questions that we think about but aren’t ready to go for yet,” he said, citing SpaceX’s agreement to share data with NASA about using rockets to bring spacecraft back to earth, technology that will be needed to bring humans to Mars.

“If I was a young engineer, I would definitely be attracted by the opportunities SpaceX has,” Pace, the former NASA official, says. “As a policy person, I would find that a distraction because I don’t see how a Mars program is really going to be sustainable. I don’t see a commercial rationale for it. I have a friend of who is also in the business who has a great phrase, ’Mars is in our hearts, but the moon is in our business plans.'”

We’ll see where Mars fits into Musk’s business plan soon enough.