Inside the race to create the next generation of satellite internet

Is the sky big enough for two multi-billion dollar satellite internet projects? In the next two years, we’ll find out if entrepreneurs driven by human betterment—one looking up at the heavens and humanity’s future, the other looking down to the earth’s neediest—can share a shot at creating the next big space product.

Is the sky big enough for two multi-billion dollar satellite internet projects? In the next two years, we’ll find out if entrepreneurs driven by human betterment—one looking up at the heavens and humanity’s future, the other looking down to the earth’s neediest—can share a shot at creating the next big space product.

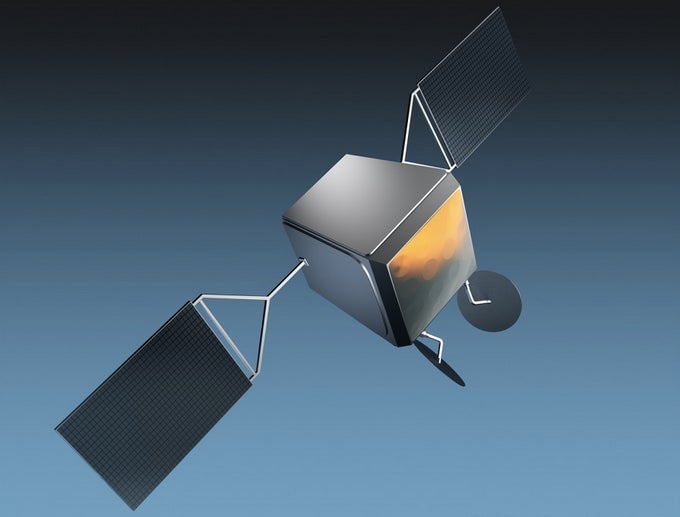

The two contenders, Greg Wyler’s OneWeb and Elon Musk’s SpaceX, both say that within the next three years they will build, launch and operate hundreds, if not thousands, of satellites flying in a low orbit around the earth to provide broadband internet. It’s an ambitious attempt to double the number of satellites orbiting earth—and succeed at a business that tends to break companies.

Industry insiders say this race has taken on the aspect of a feud: In 2014, Wyler and Musk discussed collaborating (paywall) on this effort before a shake-up left them on opposite sides. Wyler’s new company is backed by Musk’s rival in space, Virgin Galactic’s Richard Branson, and Qualcomm, while Musk raised $1 billion from Google, which had previously considered working with Wyler on satellite internet. Update, 6/25: OneWeb announced that it has secured $500 million in initial investment from additional partners Airbus, Bharti Enterprises, Hughes Network Systems, Intelsat, Coca-Cola and Totalplay.

Wyler won’t comment on SpaceX, but he told Quartz that his “hat is off to everyone in the communications industry working to bring broadband around the world.” Elon Musk and SpaceX officials declined to comment on the satellite project.

“Part of the issue is the original filings that Musk made were in late June last year, when he was still in discussion with Wyler about collaborating,” Tim Farrar, a satellite industry consultant who worked on Teledesic, a failed 1990s satellite internet play, told Quartz. “Wyler feels that Musk took his idea while they were still discussing collaboration, went to make a major filing behind his back, and stole his idea.”

The filing Farrar is discussing—with the International Telecommunications Union, which regulates the global use of the radio frequencies used by satellites—is part of the twist in this tale: The rules governing how satellites talk to their customers on earth may force the two companies to work together if they both raise enough money to put their satellites aloft.

Priority Package

Wyler’s ace in the hole is that he filed first, in 2012 and 2013, for an ITU license to transmit along a band of radio frequencies called the Ku band, which are uniquely-suited to satellite transmissions because they work best with the latest generation of satellite antennae, replacing bulkier satellite dishes. Combined with cheaper satellites flying closer to earth, engineers believe that it is possible to solve the high-lag problem that plagues current satellite internet.

Under the first-come, first-serve rules governing the ITU, if Wyler can get his satellites up and operating on those frequencies by the end 2019, he has the rights to use them, and there’s not much the ITU can do to force him to cooperate with anyone else who wants to operate on that frequency on a global level. That license, along with his expertise, had first Google, then SpaceX and ultimately Virgin Galactic, Qualcomm and Airbus ready to join Wyler’s operation.

Since Wyler’s filing, at least six other projects have registered satellite constellations in the hope he misses his deadline. The most interesting project, known as STEAM, for a 4,000 satellite internet constellation, was filed by Norway’s telecommunications regulator in June 2014.

This is the filing Farrar was referring to; its particulars match what is known about SpaceX’s plans for a satellite constellation, and industry speculation is that the constellation was registered by SpaceX. Musk has said that the company filed at the ITU, though a spokesperson declined to comment when asked if the company was behind the STEAM registration. (It is common for companies to register satellite spectrum through national telecom regulators without revealing their identities.)

Though the ITU is designed to resolve transmission conflicts for international satellites, every country can make rules about the spectrum in its jurisdiction. And in the US, the Federal Communications Commission has a different approach than the ITU: If two licensees want to use the same spectrum to transmit to people in the US, the FCC will broker its own deal between the two if the companies can’t resolve the problem themselves—the ITU priority essentially evaporates.

So, while SpaceX isn’t first in line, it can force OneWeb to share its spectrum within the US—the most lucrative market for satellite internet—by demonstrating that SpaceX could also develop the spectrum commercially. That is why the company requested permission from the FCC to launch two test satellites next year to develop its constellation.

Execution matters

And so the race is on to get those satellites into orbit. A week after SpaceX’s filing proposed flying six to eight satellites by the end of 2016, OneWeb and Airbus Space and Defense announced they would create a joint venture to manufacture 648 150 kg satellites—at a pace of four a day. Wyler tells Quartz he expects to be “beta testing” a small version of his constellation by 2017.

“We’re beyond, ‘Can we build it?'” he says, claiming his company is prepared to mass-produce satellites and their components to be assembled “like legos” for specific jobs, to an extent that he expects the manufacturing venture to change the industry, which has never mass-produced satellites before. “It’s not our primary business, but the cost of satellites will come down dramatically.”

The initial run of 10 satellites will be built in France, and are expected to cost about $500,000 each by the time manufacturing ramps up, with a total system cost of $2 billion, Wyler estimates. OneWeb says it has plans to build a satellite factory somewhere in the US for full mass production.

SpaceX has plenty of space-manufacturing chops after designing and building its Falcon rockets and Dragon space capsules, often developing techniques to build components in-house rather than paying more for an outside supplier. The company opened an office in Seattle this year to develop its satellite division, but it is unclear how long the company will take to begin production.

Where SpaceX does have a clear advantage is getting the satellites into space, since that is the company’s primary business. It remains the lowest-cost launch provider to low-earth orbit, and one of the most flexible.

OneWeb, on the other hand, will need a more expensive contract with a launch provider. It has announced that Arianespace, the leading European rocketry company, will fulfill 65 launch orders, including 21 with Russian Soyuz rockets, though it’s not clear when they those launches will occur. The company has also committed to launch ten satellites with Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic. But rocketry experts are skeptical that the Virgin will be able to build and fly a satellite-launching rocket in the next few years.

Co-existance?

If Wyler is concerned about being forced into sharing American spectrum with SpaceX, he isn’t showing it. “We are fully focused on building our system and enabling broadband access for everyone,” he tells Quartz.

Wyler’s career—at his previous satellite company, O3b, and bringing fiber-optics to Rwanda—has focused on bringing internet connectivity to low-GDP, low-density areas, places starved of “oxygen,” that is, internet access that can enable economic growth. He plans to work with existing telecom companies, with OneWeb’s data terminals—which will provide emit wi-fi, LTE and 3G signals—acting as another tool to provide access for customers.

Musk’s ambitions could be described as humanitarian in another direction. He is outspoken about the goal behind SpaceX is developing the technology necessary for humans to be a multi-planetary species—to colonize Mars.

“The satellites constitute as much, or more, of the cost of space-based activity as the rockets do. Very often, actually, the satellites are more expensive than the rocket. So, in order for us to really revolutionize space, we have to address both satellites and rockets,” Musk said at the opening of the Seattle office. “[This satellite constellation] is intended to generate a significant amount of revenue and help fund a city on Mars.”

Musk’s vision, like Wyler’s, is of a global network that improves connectivity in rich and poor countries alike. If they are both able to launch on time—a big if in the space industry—then they may find themselves competing, within the byzantine rules of global communications, to light up countries around the world with internet access.

“I’m hopeful that we can structure agreements with various countries to allow communication with their citizens but it is on a country by country basis,” Musk said in Seattle. “Not all countries will agree at first. There will always be some countries that don’t agree. That’s fine.”