Apichatpong Weerasethakul envies Hong Kong. Coming from a country that was taken over by a military coup two years ago, the acclaimed contemporary artist from Thailand says the ongoing political turmoil has not only turned his country backward, but also put his countrymen’s freedom under threat.

“It’s becoming a hybrid of Singapore and North Korea,” Weerasethakul said of his homeland.

Weerasethakul was in Hong Kong for the Sept. 17 opening of The Serenity of Madness, a traveling exhibition and his first solo show in the city. The exhibition, which runs until Nov. 27 at the nonprofit art space Para Site, shows a glimpse of the artist’s vast body of work, from video installations to photography and sculptures that reflect his grassroots-level take on Thailand’s current political system.

Weerasethakul has made award-winning films such as Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. At the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, that work earned him a Palme d’Or, one of the film world’s highest honors (never before bestowed on a Thai filmmaker). Here’s a trailer:

The exhibit opened to the public about two weeks after the dramatic election of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council. Weerasethakul noted that while Hong Kongers do not enjoy full democracy, they still have the right to vote and express themselves freely to a certain extent, which makes him feel sad about his home country.

I can’t help but [see] how backward things have become. I always had the dream of [the government] supporting cultural development, but then the government changed, and the plans were scrapped to boost military spending. There is also censorship. I envy how culture is integrated into the community in Hong Kong, and Hong Kongers are still enjoying freedom.

The growing censorship in Thailand aims at silencing critics, Weerasethakul said, and has made it harder not only to create art, but also to host exhibitions. The artist decided against showing his 2015 film Cemetery of Splendour—which revolves around a group of ill soldiers—in Thailand in order to steer clear of government censorship. Here’s a trailer for that film:

The fact that most Thais choose to keep their heads down under the military regime has made things worse, Weerasethakul believes. Meanwhile the deep-rooted Confucius culture has influenced generations to believe in the law of karma and to accept the military as an institution.

Generals come to take power in cycles. Political problems are not solved by the parliament but by force. People are used to this, and they have accepted the military. They prefer to have ‘parents’ looking after them, to keep society safe under tanks and guns.

The people of Thailand are not yet politically awakened, Weerasethakul believes. But he said some artists have decided to challenge the status quo with provocative artwork, despite facing possible “attitude adjustment.” This involves detention and being forced to sign a statement promising not to criticize the ruling regime. The authorities have summoned hundreds since 2014, he noted, among them artists.

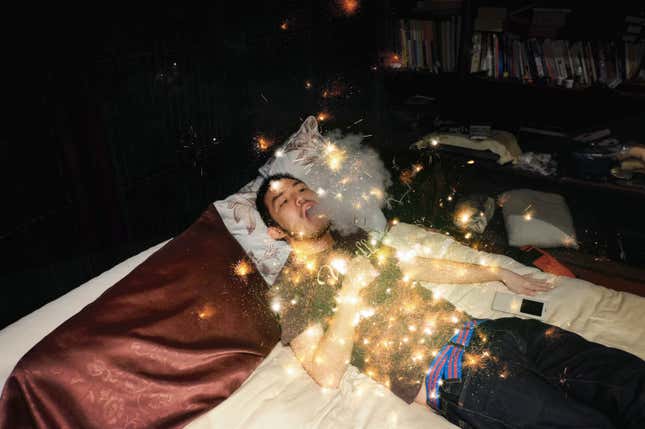

Weerasethakul said that his works are mostly a reflection of his personal memories and his take on Thai culture, but that politics inevitably creep in. His 2009 multi-screen video installation Primitive, now on show at the Tate Modern in London, is a dreamlike re-imagination of Nabua, a village in northeast Thailand. It evokes bloody but largely forgotten clashes between the Thai military and communists in the 1960s, and questions the nation’s ongoing political chaos.

“Creative people have to ask questions,” he said.