Before he settled in the United States and pursued his love for cooking, Alfred Olango was a child refugee who fled war and persecution in his home country of Uganda. Born in the capital Kampala, Olango and his family survived living in a refugee camp, before arriving in New York in 1991 in search of a better future.

In America, Olango pursued his GED, took on manufacturing and cooking jobs, and loved to play soccer. The 38-year-old was the glue of his family of nine, doted on his daughter, and hoped to one day own a restaurant.

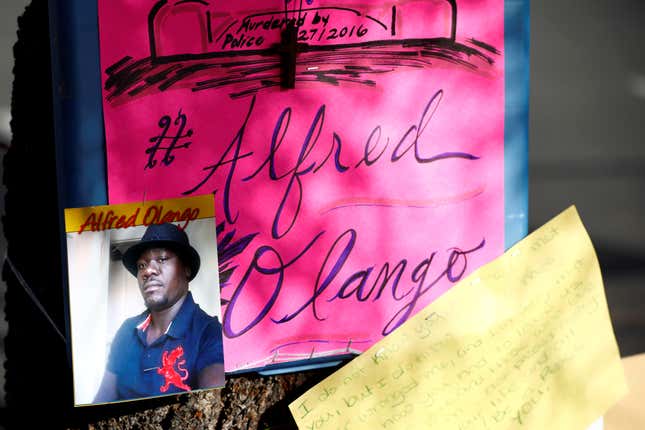

On Tuesday (Sept. 27), that dream came to an abrupt end when a police officer shot him multiple times in a parking lot in the San Diego suburb of El Cajon. His name joined the growing list—217 to be precise, according to the Mapping Police Violence project—of unarmed black men shot by police in the United States in 2016.

Police officers shot Olango a minute after arriving at the scene—even though it took them an hour to get there. Olango’s sister had originally placed the 911 call to the police, saying her brother was acting out. The police said that Olango refused to comply with their instructions, and paced back and forth as the two officers tried to talk to him. After he “rapidly drew an object” from his pocket and took a “shooting stance,” the two officers simultaneously tasered and shot him. The object was later identified as a vape smoking device.

At a tearful press conference on Thursday (Sept. 30), Olango’s mother, Pamela Benge, expressed the pain of her family’s escape from war, only for her son to face death in the country where they sought refuge. “Yes, we are refugees. But that doesn’t justify that we should be killed because of being refugees,” she said. “I pray that things should be different.”

Benge also expressed her fear and concern over recent police shootings of black men around the country. “I didn’t know that the next time it would be me,” she said, showing solidarity and connection with other families who have lost loved ones to shootings. “It has reached me. It has come.”

Olango’s mother dispelled earlier reports that her son suffered from mental illness, saying he had become distressed over losing a friend. Her son, she said, was a man whose mind at the time of the incident “was not communicating.”

“He had no gun—he was not mental,” she said. “He was just having a mental breakdown. There is a difference.”

Olango was ordered twice for deportation in the past after having several problems with the law. The prescribed run-ins allegedly included selling cocaine, driving drunk and illegally possessing handguns.

But after his native Uganda refused to take him in, Olango was allowed to stay in the country. This was based on a Supreme Court decision that barred detaining foreign nationals for more than six months if the deportation was unlikely. According to a statement from the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Olango, who was ordered to appear regularly before them, stopped reporting in Feb. 2015.

Olango’s killing has sparked demonstrations in San Diego, with protestors blocking off roads and confronting police. Olango’s mother has called for calm and peaceful protest, reminding people of the brutality of war. “I don’t want war. If you’ve seen war, you would never, ever want to step near where there’s war,” she said at the press briefing.

Olango’s killing has also drawn condolences and sharp condemnation from leaders and celebrities in the US and across the world. The US embassy in Kampala put out a Facebook post extending condolences to Olango’s family and friends. Uganda’s foreign ministry also directed its embassy in Washington DC to establish the circumstances surrounding the shooting, according to the Daily Monitor newspaper.

At the press conference on Thursday, Benge painted a loving picture of her son and called for the police killings to stop.

“My son was a good, loving young man,” she said. “I wanted his future to be longer than that.”