Wishful thinking is a powerful force indeed.

Yesterday (Oct. 26), Newt Gingrich, the disgraced former Speaker of the House, tried to buck up supporters of Donald Trump worried about public opinion surveys showing he lags behind Hillary Clinton less than two weeks away from the presidential election.

“I watched Brexit,” he told NBC news. “I have a pretty good idea what’s going to happen.”

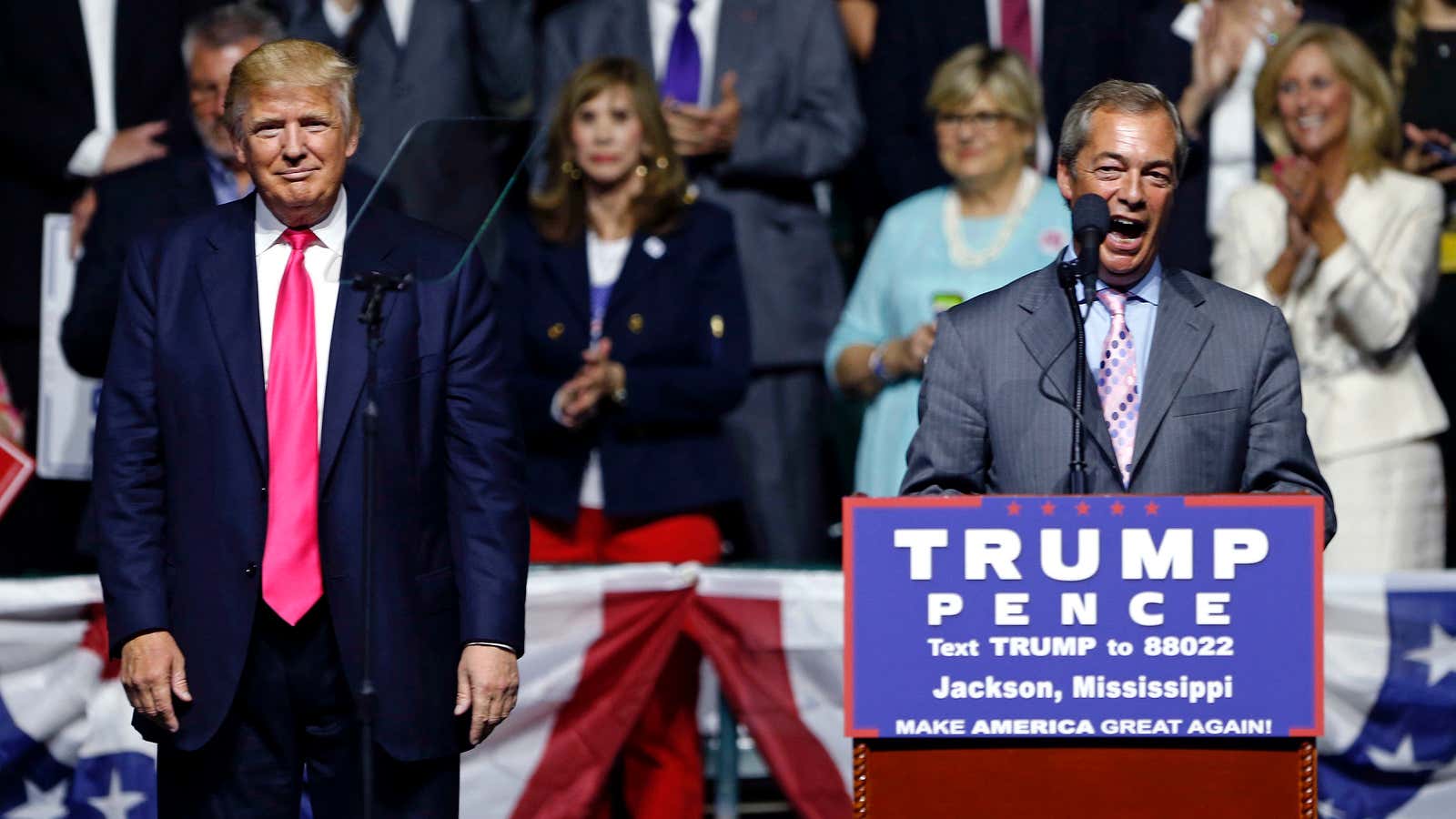

Because Gingrich and even Mr. Brexit himself have been harping on about this for a while, we know what he expects: The polls will prove to be wrong, and Trump will win a surprise victory on Nov. 8.

So please note well: The polls were not wrong about Brexit. Anyone who read incorrect results into them did so for the exact same reason that Gingrich is wrong now: Wishful thinking.

The final vote for Brexit, the UK’s June 23, 2016 referendum on whether it should leave the European Union, turned out to be 52% in favor of leaving and 48% to remain. What did the polls say before the vote? Thanks to the internet, we can look back and see. Many media outlets in the UK adopted the policy of collecting public polls and averaging them, a best practice for dealing with volatile public opinion.

The Financial Times‘ tracker offered an average of 48% Remain, 46% Leave and 6% undecided ahead of the vote. The Economist’s final tracker found Remain and Leave tied at 44% each, with 9% saying “don’t know.” I can’t quite figure out where the BBC’s polling average wound up, but their last commentary is “a final set of polls continues to give an unclear picture of the referendum outcome.” In other words, a unified message came from poll analysts: This is too close to call. That’s especially true given the the margin of error of 3% in most surveys of 1,000 or more people, which characterizes most of these national polls.

Indeed, an average of the results of 25 surveys—see them all down here—taken in the final two weeks of the campaign show Leave in the lead with support from 45.5% of voters, Remain with 45%, and 8.9% undecided.

For a longer look back, this chart shows the polls tightening between May 1 and the referendum:

What about on the final day? Six pollsters came out with surveys on June 22; two showed a Leave victory, three showed a small Remain victory, and one—an online-only overnight poll that looked like an outlier even at the time—showed a massive Remain victory.

The surveys showing a small Remain victory were circumspect. YouGov wrote that “our current polling suggests the race is too close to call,” while the chairman of polling firm ComRes said that “support for Remain is broad and shallow … [i]n contrast, support for Leave is deeper but narrower.”

It is safe to say that pollsters didn’t fail to forecast what would happen during the Brexit referendum, but rather that they accurately discovered the public was closely divided on an issue of controversy. Anyone looking at those numbers and confidently predicting any outcome was either willfully spinning the facts or desperately hoping undecided voters would resolve a tie in their favor. It seems that many pundits and investors expecting a Remain victory simply assumed undecided voters would move toward to the status quo as the critical day neared. That’s right into the category of wishful thinking.

Pollsters, of course, aren’t infallible. During Brexit, a record-high voter turnout for the referendum threw everything off. It was the highest in more than two decades, including 3 million more people than voted in the previous general election. The pollsters didn’t come to a consensus on who would actually participate, leading to their inconsistent predictions.

How does that compare to today’s surveys of US public opinion ahead of the Nov. 8 election? Averages of national polls consistently show a lead for Clinton that exceeds the margin of error—a six point lead at Huffington Post, and a 4.9 point lead at Real Clear Politics. That’s been the case essentially since August. State-level polling tends to confirm, rather than question, the national polling averages. And the latest polls show that Clinton supporters are becoming increasingly excited about her candidacy.

Trump’s chances of victory depend far more on people who haven’t voted before defying historical expectations and showing up than they do on the voters who are too shy to admit voting for him in polls. A surge of white voters turning out for Trump, or large numbers of young people and minorities unexpectedly staying home instead of voting for Clinton, could tip the scales on Nov. 8. Today, the Trump’s campaign described “voter suppression” operations targeting just those Clinton voters.

Since Clinton’s margin is far bigger than Remain’s was, it would be a far bigger surprise if she lost, and we have more than one reason to think that’s unlikely: it’s easier to predict turnout for a presidential election than a referendum, Trump is polling worse than the 2012 Republican candidate did among white voters, and a new survey suggests that Clinton is doing as well as the 2012 Democrat among young voters.

Polls are just one more tool we can use to learn about elections. Leading up to the Brexit vote in the UK, the polls told the public about a close, volatile referendum. In the US today, they are telling the public about a stable race with an obvious outcome. Those polls may yet be confounded, but don’t let your aspirations convince you they’re saying something else.

* * *

Here, for reference, are the major polls released during the last thirteen days of the Brexit referendum, as collected by the Financial Times: