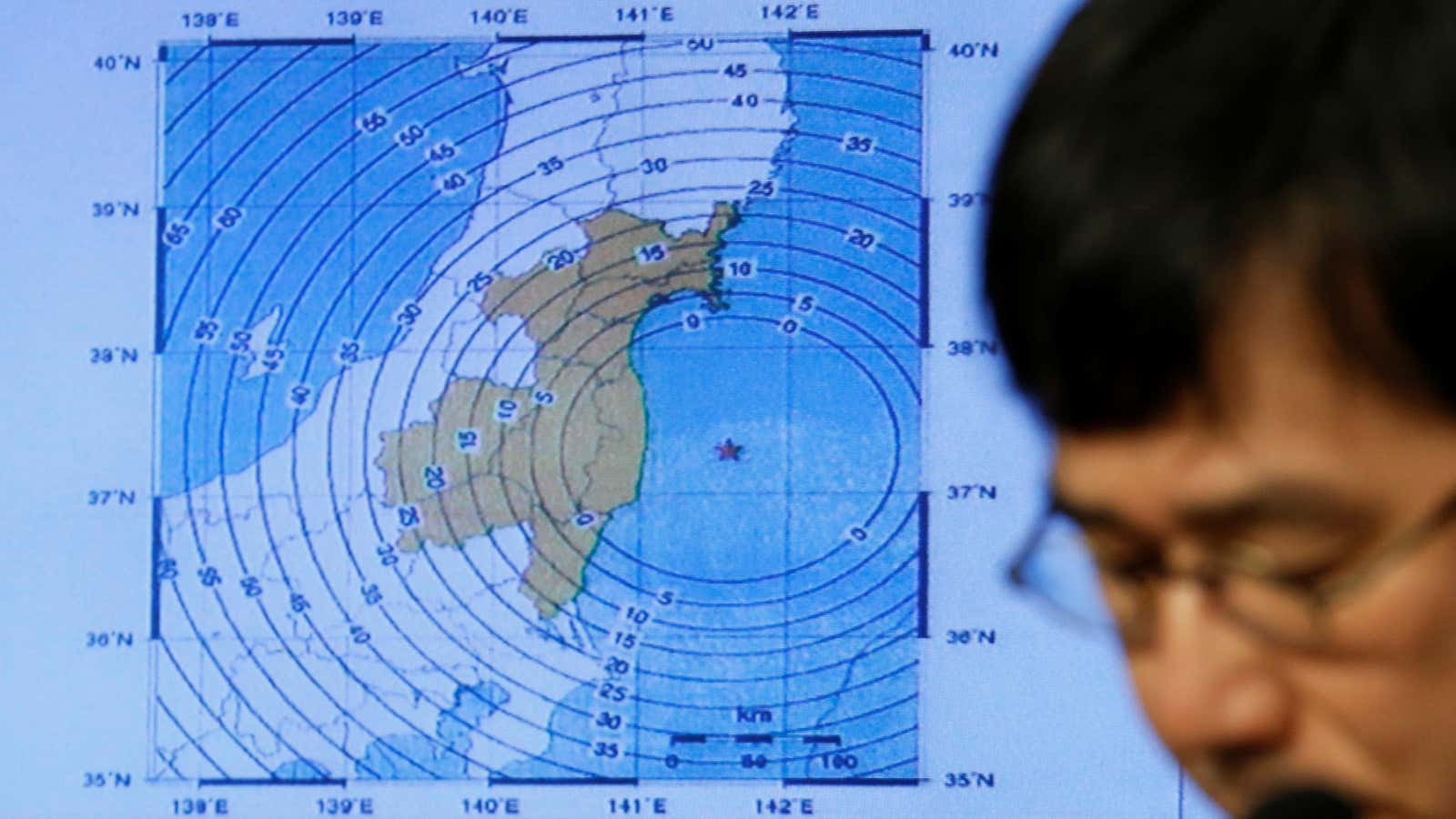

Early on Nov. 22, the residents of Fukushima, Japan were woken by loud sirens. At 6am local time, a magnitude 6.9 earthquake had struck off the coast. Authorities issued a warning that a tsunami, estimated to be about 3 meters (10 feet) high, could hit the coast within hours, and resident were asked to evacuate immediately and move to higher ground.

Though Japan has seen similar magnitude earthquakes in recent years, the proximity of this one to the devastating 2011 quake raised anxieties. The magnitude 9.0 earthquake in 2011 triggered tsunami waves as high as 4 meters crashing onto the coast, killing more than 15,000 people. The tsunami also destroyed emergency cooling generators at the Fukushima nuclear reactor, which led to overheating and leakage of radioactive fuel into surrounding water.

The waves that hit the Japanese coast on Tuesday topped out at about 1.4 meters high, and there haven’t been any reported deaths. The Fukushima plant had a minor problem with its spent-fuel pump, but has since been declared intact and safe. While there are people who suffered minor injuries, no serious injuries or damage to infrastructure has been reported.

Tuesday’s quake has a direct connection to the 2011 disaster: scientists believe that it was actually an aftershock of that earthquake—the largest since those that occurred in the immediate aftermath of the initial magnitude 9.0 quake.

“For an earthquake to be classified as an aftershock, it has to satisfy two conditions,” says Stephen Hicks, a seismologist formerly at Liverpool University. First, it must be in the same area as the initial quake. Second, it must occur in a period when the seismic activity in the area hasn’t gone back to average that existed before the large quake.

Ever since the 2011 earthquake, seismic activities off the northern coast of Japan haven’t gone back to the pre-quake levels. Researchers at Japan’s meteorology agency expect more aftershocks, some as large as the one on Tuesday.

“Before March 11, 2011 we didn’t see much of this type of earthquake in the area. But since the major calamity, we’ve started to see it in the region,” Masanobu Shishikura of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, told the Japan Times.

A magnitude 9.0 earthquake only occurs once or twice in a century, which is good considering that size quake releases energy equivalent to 30,000 times the amount discharged by the atom bomb dropped on Nagasaki. Some earthquake occur when the different tectonic plates that make up the Earth’s crust collide abnormally. The energy released in the process at magnitude 9.0 is enough to push down on the the thick but fluid mantle right beneath the Earth’s crust, which then eventually rebounds—just like a rubber duck pushed into water would rebound. This rebound, however, occurs over many years, and it’s one reason why aftershocks are being felt even though it has been more than five years since the big earthquake.