The Chinese government may finally be reining in the use of wealth management products (WMPs), the risky investment vehicles that held some $1.2 trillion in assets (largely households) at the end of 2012. China Real Time reports that banks issued 8.8% fewer WMPs in April compared with March, after the government cracked down on bank issuances.

This should help protect households from risky debt. But whether it gives the government more control over shadow banking is another story.

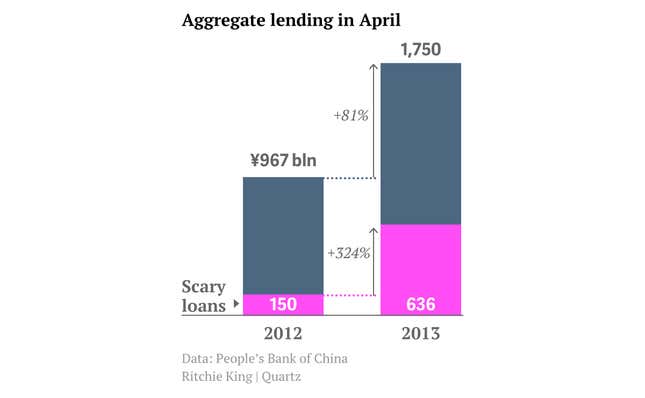

Overall loan growth continued to boom in April. That includes conventional lending and the types of debt that flow into what’s called “shadow banking.” Here’s a look at that:

If the banking regulator is successfully stamping out WMPs—which provide vehicles for financing these shadow loans—why the steep growth in shadow banking?

One possibility is that recipients of conventional loans—typically state-owned enterprises (SOEs)—are investing in real estate instead of their own businesses because of overcapacity. Anne Stevenson-Yang, founder of Beijing-based J Capital Research, explained this trend to Quartz recently.

In many areas 50% of plants sit idle, which “means when you take on debt you can’t pay through what you earn,” said Stevenson-Yang. “So as that started to happen, companies would take their cash…and put it into property. The property bubble was providing 30-40% returns for long time, and that masked bad things in the larger economy.”

The shadow banking in real estate rages on, according to the 21st Century Business Herald, which reported today that demand for trust company loans is “quietly picking up” (link in Chinese). The securities funding construction via trusts aren’t backed by collateral, according to the report.

Junheng Li, head of research at China-focused research firm JL Warren Capital agrees that SOEs are behind the rush into the real estate market. ”The estimate for corporate leverage ranges from 150% to more than 200%. Even the low end of the range suggests that China now has the highest corporate debt to GDP in the world, not to mention much of the debt is non-performing loans, predominantly borrowed to invest in real estate projects,” she tells Quartz, noting that if you add “accounts receivable,” payments that a business hasn’t yet collected, the number is more like 220%. “That [has] to be rolled over with new issuance of debt—a classic example of ‘extend and pretend’ or ‘delay and pray.'”

If so, the bad debt that many worry is plaguing Chinese banks is plaguing corporate balance sheets, too.