Leaving aside monetary policy, the textbook Keynesian remedy for recession is to increase government spending or cut taxes. The obvious problem with that is that higher government spending and lower taxes tend to put the government deeper in debt. So the announcement on April 15, 2013 by University of Massachusetts at Amherst economists Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin that Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff had made a mistake in their analysis claiming that debt leads to lower economic growth has been big news. Remarkably for a story so wonkish, the tale of Reinhart and Rogoff’s errors even made it onto the Colbert Report. Six weeks later, discussions of Herndon, Ash and Pollin’s challenge to Reinhart and Rogoff continue in earnest in the economics blogosphere, in the Wall Street Journal, and in the New York Times.

In defending the main conclusions of their work, while conceding some errors, Reinhart and Rogoff point out that even after the errors are corrected, there is a substantial negative correlation between debt levels and economic growth. That is a fair description of what Herndon, Ash and Pollin find, as discussed in an earlier Quartz column, “An Economist’s Mea Culpa: I relied on Reinhardt and Rogoff.” But, as mentioned there, and as Reinhart and Rogoff point out in their response to Herndon, Ash and Pollin, there is a key remaining issue of what causes what. It is well known among economists that low growth leads to extra debt because tax revenues go down and spending goes up in a recession. But does debt also cause low growth in a vicious cycle? That is the question.

We wanted to see for ourselves what Reinhart and Rogoff’s data could say about whether high national debt seems to cause low growth. In particular, we wanted to separate the effect of low growth in causing higher debt from any effect of higher debt in causing low growth. There is no way to do this perfectly. But we wanted to make the attempt. We had one key difference in our approach from many of the other analyses of Reinhart and Rogoff’s data: we decided to focus only on long-run effects. This is a way to avoid getting confused by the effects of business cycles such as the Great Recession that we are still recovering from. But one limitation of focusing on long-run effects is that it might leave out one of the more obvious problems with debt: the bond markets might at any time refuse to continue lending except at punitively high interest rates, causing debt crises like that have been faced by Greece, Ireland, and Cyprus, and to a lesser degree Spain and Italy. So far, debt crises like this have been rare for countries that have borrowed in their own currency, but are a serious danger for countries that borrow in a foreign currency or share a currency with many other countries in the euro zone.

Here is what we did to focus on long-run effects: to avoid being confused by business-cycle effects, we looked at the relationship between national debt and growth in the period of time from five to 10 years later. In their paper “Debt Overhangs, Past and Present,” Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, along with Vincent Reinhart, emphasize that most episodes of high national debt last a long time. That means that if high debt really causes low growth in a slow, corrosive way, we should be able to see high debt now associated with low growth far into the future for the simple reason that high debt now tends to be associated with high debt for quite some time into the future.

Here is the bottom line. Based on economic theory, it would be surprising indeed if high levels of national debt didn’t have at least some slow, corrosive negative effect on economic growth. And we still worry about the effects of debt. But the two of us could not find even a shred of evidence in the Reinhart and Rogoff data for a negative effect of government debt on growth.

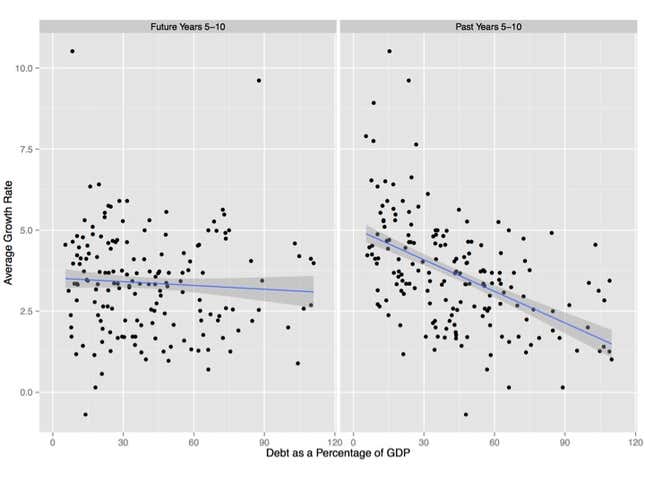

The graphs at the top show show our first take at analyzing the Reinhardt and Rogoff data. This first take seemed to indicate a large effect of low economic growth in the past in raising debt combined with a smaller, but still very important effect of high debt in lowering later economic growth. On the right panel of the graph above, you can see the strong downward slope that indicates a strong correlation between low growth rates in the period from ten years ago to five years ago with more debt, suggesting that low growth in the past causes high debt. On the left panel of the graph above, you can see the mild downward slope that indicates a weaker correlation between debt and lower growth in the period from five years later to ten years later, suggesting that debt might have some negative effect on growth in the long run. In order to avoid overstating the amount of data available, these graphs have only one dot for each five-year period in the data set. If our further analysis had confirmed these results, we were prepared to argue that the evidence suggested a serious worry about the effects of debt on growth. But the story the graphs above seem to tell dissolves on closer examination.

Given the strong effect past low growth seemed to have on debt, we felt that we needed to take into account the effect of past economic growth rates on debt more carefully when trying to tease out the effects in the other direction, of debt on later growth. Economists often use a technique called multiple regression analysis (or “ordinary least squares”) to take into account the effect of one thing when looking at the effect of something else. Here we are doing something that is quite close both in spirit and the numbers it generates for our analysis, but allows us to use graphs to show what is going on a little better.

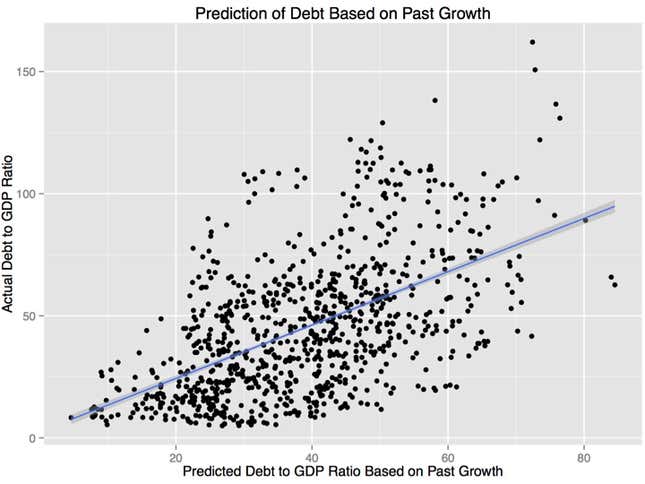

The effects of low economic growth in the past may not all come from business cycle effects. It is possible that there are political effects as well, in which a slowly growing pie to be divided makes it harder for different political factions to agree, resulting in deficits. Low growth in the past may also be a sign that a government is incompetent or dysfunctional in some other way that also causes high debt. So the way we took into account the effects of economic growth in the past on debt—and the effects on debt of the level of government competence that past growth may signify—was to look at what level of debt could be predicted by knowing the rates of economic growth from the past year, and in the three-year periods from 10 to 7 years ago, 7 to 4 years ago and 4 to 1 years ago. The graph below, labeled “Prediction of Debt Based on Past Growth” shows that knowing these various economic growth rates over the past 10 years helps a lot in predicting how high the ratio of national debt to GDP will be on a year by year basis. (Doing things on a year by year basis gives the best prediction, but means the graph has five times as many dots as the other scatter plots.) The “Prediction of Debt Based on Past Growth” graph shows that some countries, at some times, have debt above what one would expect based on past growth and some countries have debt below what one would expect based on past growth. If higher debt causes lower growth, then national debt beyond what could be predicted by past economic growth should be bad for future growth.

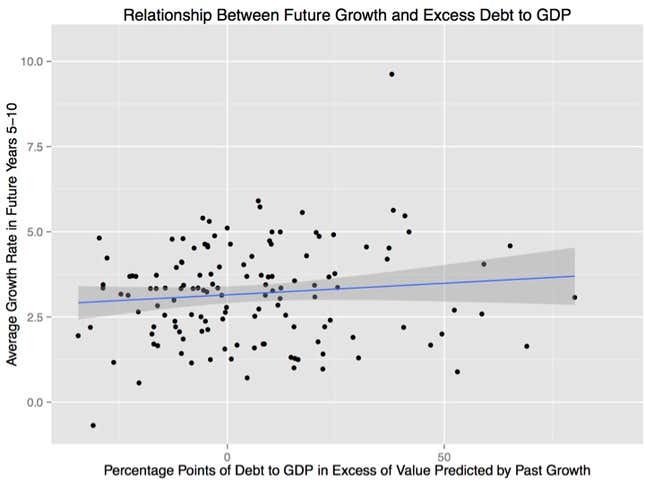

Our next graph below, labeled “Relationship Between Future Growth and Excess Debt to GDP” shows the relationship between a debt to GDP ratio beyond what would be predicted by past growth and economic growth 5 to 10 years later. Here there is no downward slope at all. In fact there is a small upward slope. This was surprising enough that we asked others we knew to see what they found when trying our basic approach. They bear no responsibility for our interpretation of the analysis here, but Owen Zidar, an economics graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, and Daniel Weagley, graduate student in finance at the University of Michigan were generous enough to analyze the data from our angle to help alert us if they found we were dramatically off course and to suggest various ways to handle details. (In addition, Yu She, a student in the master’s of applied economics program at the University of Michigan proofread our computer code.) We have no doubt that someone could use a slightly different data set or tweak the analysis enough to make the small upward slope into a small downward slope. But the fact that we got a small upward slope so easily (on our first try with this approach of controlling for past growth more carefully) means that there is no robust evidence in the Reinhart and Rogoff data set for a negative long-run effect of debt on future growth once the effects of past growth on debt are taken into account. (We still get an upward slope when we do things on a year-by-year basis instead of looking at non-overlapping five-year growth periods.)

Daniel Weagley raised a very interesting issue that the very slight upward slope shown for the “Relationship Between Future Growth and Excess Debt to GDP” is composed of two different kinds of evidence. Times when countries in the data set, on average, have higher debt than would be predicted tend to be associated with higher growth in the period from five to 10 years later. But at any time, countries that have debt that is unexpectedly high not only compared to their own past growth, but also compared to the unexpected debt of other countries at that time, do indeed tend to have lower growth five to 10 years later. It is only speculating, but this is what one might expect if the main mechanism for long-run effects of debt on growth is more of the short-run effect we mentioned above: the danger that the “bond market vigilantes” will start demanding high interest rates. It is hard for the bond market vigilantes to take their money out of all government bonds everywhere in the world, so having debt that looks high compared to other countries at any given time might be what matters most.

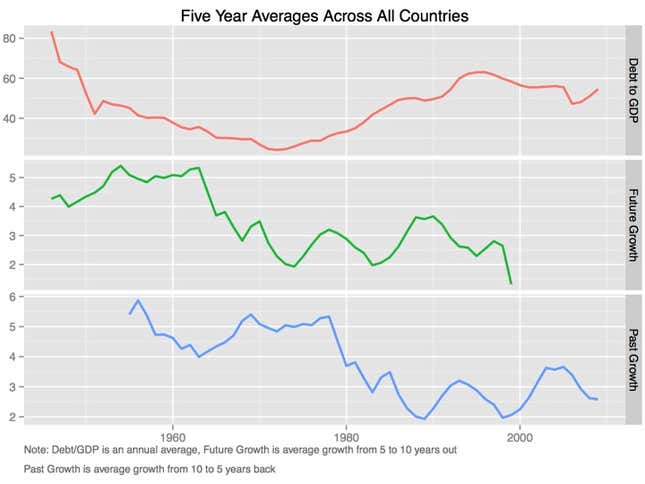

Our view is that evidence from trends in the average level of debt around the world over time are just as instructive as evidence from the cross-national evidence from debt in one country being higher than in other countries at a given time. Our last graph (just above) shows what the evidence from trends in average levels over time looks like. High debt levels in the late 1940s and the 1950s were followed five to 10 years later with relatively high growth. Low debt levels in the 1960s and 1970s were followed five to 10 years later by relatively low growth. High debt levels in the 1980s and 1990s were followed five to 10 years later by relatively high growth. If anyone can come up with a good argument for why this evidence from trends in the average levels over time should be dismissed, then only the cross-national evidence about debt in one country compared to another would remain, which by itself makes debt look bad for growth. But we argue that there is not enough justification to say that special occurrences each year make the evidence from trends in the average levels over time worthless. (Technically, we don’t think it is appropriate to use “year fixed effects” to soak up and throw away evidence from those trends over time in the average level of debt around the world.)

We don’t want anyone to take away the message that high levels of national debt are a matter of no concern. As discussed in “Why Austerity Budgets Won’t Save Your Economy,” the big problem with debt is that the only ways to avoid paying it back or paying interest on it forever are national bankruptcy or hyper-inflation. And unless the borrowed money is spent in ways that foster economic growth in a big way, paying it back or paying interest on it forever will mean future pain in the form of higher taxes or lower spending.

There is very little evidence that spending borrowed money on conventional Keynesian stimulus—spent in the ways dictated by what has become normal politics in the US, Europe and Japan—(or the kinds of tax cuts typically proposed) can stimulate the economy enough to avoid having to raise taxes or cut spending in the future to pay the debt back. There are three main ways to use debt to increase growth enough to avoid having to raise taxes or cut spending later:

1. Spending on national investments that have a very high return, such as in scientific research, fixing roads or bridges that have been sorely neglected.

2. Using government support to catalyze private borrowing by firms and households, such as government support for student loans, and temporary investment tax credits or Federal Lines of Credit to households used as a stimulus measure.

3. Issuing debt to create a sovereign wealth fund—that is, putting the money into the corporate stock and bond markets instead of spending it, as discussed in “Why the US needs its own sovereign wealth fund.” For anyone who thinks government debt is important as a form of collateral for private firms (see “How a US Sovereign Wealth Fund Can Alleviate a Scarcity of Safe Assets”), this is the way to get those benefits of debt, while earning more interest and dividends for tax payers than the extra debt costs. And a sovereign wealth fund (like breaking through the zero lower bound with electronic money) makes the tilt of governments toward short-term financing caused by current quantitative easing policies unnecessary.

But even if debt is used in ways that do require higher taxes or lower spending in the future, it may sometimes be worth it. If a country has its own currency, and borrows using appropriate long-term debt (so it only has to refinance a small fraction of the debt each year) the danger from bond market vigilantes can be kept to a minimum. And other than the danger from bond market vigilantes, we find no persuasive evidence from Reinhart and Rogoff’s data set to worry about anything but the higher future taxes or lower future spending needed to pay for that long-term debt. We look forward to further evidence and further thinking on the effects of debt. But our bottom line from this analysis, and the thinking we have been able to articulate above, is this: Done carefully, debt is not damning. Debt is just debt.