If there was ever a global currency war—and we’ve long been skeptical—Brazil’s Finance Minister Guido Mantega just effectively announced his country’s surrender by slashing its tax on foreign investment (IOF) from 6% to zero. Mantega says the move is needed to boost Brazilian growth by reviving slowing foreign investment. But the move isn’t likely to jolt foreign investors, who are more worried about the overall trajectory of Brazil’s faltering economy.

When it was announced in 2010, the tariff was supposed to dissuade yield-seeking investors from pouring hot money into Brazilian markets. The onslaught of foreign investment drove up the value of Brazil’s currency, the real, making Brazilian exports more expensive for foreign buyers.

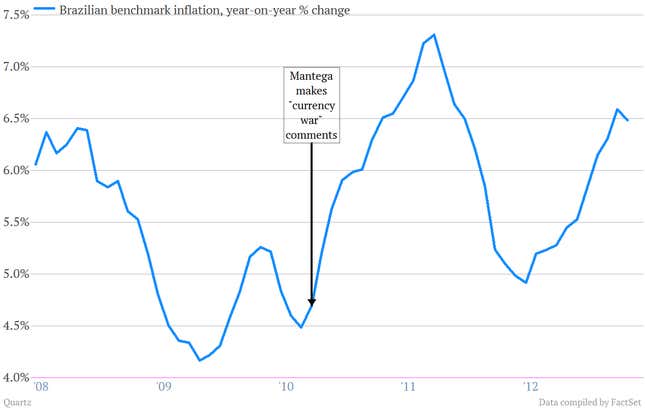

Now Brazil is suffering from persistently high inflation. The foreign investment tax should help address that by strengthening the real, which increases the purchasing power of Brazilian consumers and keeps prices in check. In April, year-on-year inflation was 6.49%, which approaches the high end of the central bank’s comfort zone of 6.5%. In 2010, the inflation rate was below 5%.)

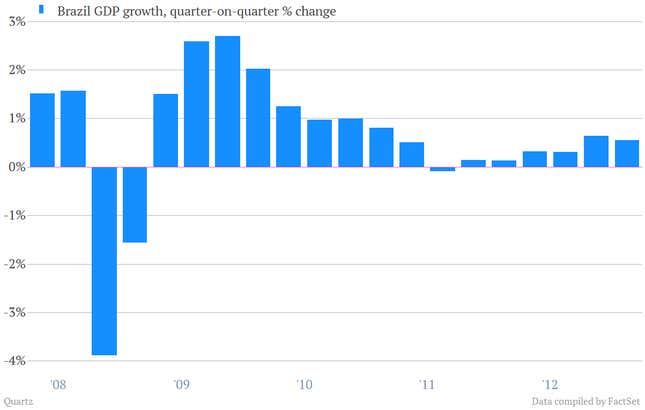

To tame the rise in prices, Brazil’s central bank has increased its benchmark interest rate to 8%. But raising interest rates too much would slow economic growth at a time when Brazil’s economy is weak. In the first three months of 2013, Brazil’s economy grew only 0.6%.

There’s a word for this predicament: stagflation. Mantega is “dealing with the inflation part, but it’s not going to solve the ‘stag’ part,” said William Cline, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

To really jolt growth, Mantega will need to pander more to global investors who see cracks in Brazil’s growth model. One big red flag: the government is relying too heavily on cheap borrowing to drive domestic consumption.