Listen, we understand the instinct. It’s not easy to collect clicks on blog posts about central bank interest-rate differentials. Seriously. We know

…Oh, how we know.

That’s why it was manna from heaven back in September 2010 when Brazilian finance minister Guido Mantega departed from the pallid technocratic language that dominates such discussions and complained loudly about an “international currency war.” Finally! Something to hang our hats on! War! The internet loves war!

At the time Mantega was voicing concern about the cheap-money policies being run by central banks in the largest economies, such as the US Federal Reserve. The Fed—and other central banks—were trying to make it cheaper to borrow, in part, by creating vast reserves of new money. (This is the famous quantitative easing, which got that name because the banks are “easing” monetary policy by boosting the “quantity” of money. If there’s a greater supply of money but the same demand, then the “price” of money, which is the interest rate, goes down.)

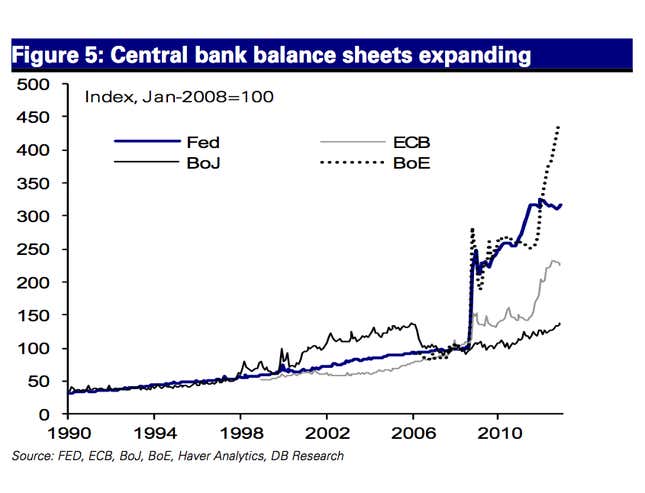

Here’s what all that money creation—wonks describe it as central bank “balance sheet expansion”—has looked like over the last few years, via a chart from Deutsche Bank.

This new money drove the value of those currencies down sharply against other currencies. In other words, currencies in which there was no quantitative easing, like the Brazilian real, strengthened against those in which there was, like the dollar.

A stronger real is, of course, bad for Brazil’s exports, because it makes them more expensive for foreign buyers, compared to US goods. Hence Mantega’s complaint—an entirely appropriate one for a finance minister.

Fast-forward to today. We’ve still got central banks creating money like crazy. The Federal Reserve is on its third round of quantitative easing (or fourth, depending how you count). The Bank of Japan looks like it’s going to join the party. And so, from some of our esteemed colleagues in the financial punditry profession, we’re starting to hear murmurings that a “currency war” is again in the offing.

Wrong!

Like tango and tennis, a war requires two (at least) to take part.

A few years ago there really was a currency war—or at least a few currency skirmishes. After a flood of freshly created American cash poured into markets like Brazil, driving its currency higher, Brazil started to push back, slapping a tax on foreign bond buyers to try to curb the speculative inflows. Japan—which at that time wasn’t creating a ton of money—launched what came to be known as the Yentervention to keep its currency from getting too strong. Even the normally neutral Swiss took a stand, creating francs and using them to buy up other currencies in order to help its export sector. That policy has left the Swiss central bank holding a ton of foreign currencies, as this Wall Street Journal chart shows.

Those were their belligerent responses to what they saw as acts of currency war.

The situation is now different. In Brazil, persistently high inflation has become an increasingly tricky problem lately. Likewise, in other big emerging markets such as China, Russia, and India. And a stronger currency is a natural counterweight to inflation. JP Morgan economists recently pointed out that strengthening currencies “help explain the recent declines in inflation in Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru.”

This means that the countries that were the first to openly declare a state of currency war back in 2010—Yes, you, Brazil—will likely be more willing to accept a stronger currency now, to keep inflation under control. So while they might accuse the US of declaring currency war again, they’re much less likely to take up arms themselves. That doesn’t mean currency war is going to disappear from the debate. But it suggests the threat is rather overblown.