Many consider the H-1B visa to be the pipeline that helped America build the world’s biggest tech hub in Silicon Valley. Others believe the visa’s success has come at the expense of American jobs.

How did the visa become such a painful touchpoint in the debate over US immigration reform?

The goal of the H-1B visa program, created by president George H.W. Bush in 1990, was to transform how American companies hired top talent. The temporary, non-immigrant visa category allows highly skilled foreign workers to live and work in the US for up to six years, after which they can apply for a green card. It has become an extremely sought-after program, attracting talented workers in fast-growing specialized fields such as research, engineering, and computer programming.

Over the last 30 years, beneficiaries of the visa, now numbering in the millions, have filled a massive skills gap in critical STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). Professionals who moved to the US on the H-1B visa and settled permanently have gone on to lead some of the country’s largest companies, including Google, Microsoft, and PepsiCo.

But the visa category has also attracted immense criticism. Decades after its creation by one Republican president, another Republican president has targeted it as part of an anti-immigration clampdown. The Trump administration has capitalized on existing resentments around the program—that it allows companies to hire cheap labor from abroad—to make it harder for people to get the visa.

In June, Trump temporarily banned the issuing of nonimmigrant work visas like the H-1B outright, calling them detrimental to the US interests in the midst of an economy-wrecking pandemic. (The Brookings Institution estimated the ban cost the US economy $100 billion the day it was issued, based on the dip in the market value of Fortune 500 companies that followed the executive order.)

The H-1B visa is not perfect. But experts say reforming it—instead of just restricting it—could actually boost productivity, innovation, and even create jobs for American workers.

“Immigrants have and do make America great. There is no denying this,” said New York-based immigration attorney Neil A. Weinrib. “Immigrants have fueled some of America’s most prominent companies and startups. America runs on immigrants.”

The H-1B visa has had an indelible impact not just on the US, but also on countries like India, a primary beneficiary of the program. Tracing its evolution sheds light on some of the major issues of immigration reform facing the next US government, as a divided country debates the role of immigrants in shaping its future.

Table of contents

The history of the H-1B | The case against the H-1B | The Trump administration crackdown | The case for the H-1B | The need for reform | A referendum on foreign workers

The history of the H-1B

The H-1B visa category was established as part of a broad package of US immigration reforms. The Immigration Act of 1990 credited the “special role of immigrants to America,” and, in Bush’s words, was intended to “promote a more competitive economy,” and infuse the ranks of America’s scientists and engineers and educators “with new blood and new ideas.” The goal was to help American firms hire the crème de la crème of talent from around the world, especially in advanced tech fields.

Successfully applying for the visa is not easy. Applicants and employers face a lengthy procedure that includes a lot of paperwork and a steep fee. It also requires a big dose of luck.

Employers pay between $1,710 and $6,460 to sponsor an individual for a visa depending on the employer’s size and timelines. Over the last two decades, companies have paid over $5 billion in H-1B visa fees. A portion of this fee (pdf) funds the National Science Foundation and the retraining of American workers through the Department of Labor.

Applicants require a bachelor’s degree at the minimum. Employers are required to attest that bringing the person on will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of the American workers at the same level by showing how the workers stack up against surveys of the labor market they are being hired in. The employer must also give existing workers notice of their intention to hire a foreign professional.

After all the paperwork, getting an H-1B visa is still a matter of chance.

If the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) receives more applications than the annual cap, a computerized lottery decides the fate of the applicants. Currently, the annual cap is at 65,000 visas, with an additional 20,000 for foreign professionals who graduate with a master’s degree or doctorate from a US institution. At its peak in 2003, the H-1B program granted 195,000 visas.

Thousands more people apply than there are visas available—over 275,000 H-1B applications were filed for the 2021 financial year—the highest in 15 years. As a result, applicants only have about a 40% chance of their application being successful. (Fees are refunded for those not selected in the lottery.)

Eight times between 2008 to 2020, the annual H-1B cap was reached within the first five business days of the lottery opening. Each year, thousands of skilled applicants were left out despite meeting all criteria. This has led to a cottage industry of organizations claiming to be able to help improve the chances of a successful application—from immigration firms to a 500-year old “H-1B temple” that attracts scores of devotees.

The case against the H-1B

IT companies have been accused of misusing H-1B visas since the program began. Critics say loopholes in the visa’s criteria allow companies to bring foreign workers on paltry salaries and have resulted in so-called “body shops“—third party firms that recruit and then subcontract out skilled H-1B recipients for profit.

There’s no denying that the program has been misused and exploited. While H-1B rules require companies to pay a prevailing wage, companies that are paying $60,000 and above per employee, or hire people with a master’s degree, are exempt from this rule. In some cases, employees are brought to the US with the promise of a lucrative American job, only to be paid less than they might have back home.

The fact that the employee’s work status is tied to their sponsoring company can make them vulnerable to abuse, says Rajiv Dabhadkar, founder and CEO of Mumbai-based National Organisation for Software and Technology Professionals. Misuse of this provision has meant that “foreign guest workers serving involuntary servitude grew in large numbers over the years.”

Firms that sponsor large numbers of H-1B workers have been accused of doing so at the expense of American workers. In 2015, workers at southern California’s largest utility company, which hires hundreds of IT employees and contract workers, alleged that Indian IT giants Infosys and Tata Consultancy Services had supplanted them with Indian workers. In the aftermath, several big-name firms like Disney, Hertz, and Toys R Us leveled similar allegations. In some cases, they argued that US workers with superior skills were having to train their foreign counterparts.

In 2017, Oracle was sued for “hiring discrimination against qualified White, Hispanic, and African-American applicants in favor of Asian applicants, particularly Asian Indians.”

Indians have been at the pole end of much of this criticism as they seek and receive three-quarters of H-1B visas each year. Indian IT giant Infosys has been accused of misusing the temporary visitor visa B-1 in lieu of H-1B on more than one occasion.

The Trump administration crackdown

A rise in nationalism has led many Americans to push back on the country’s identity as a “land of immigrants.” The Trump administration has capitalized on that backlash to make the US a pretty hostile place for foreign talent.

One way the administration has enacted its anti-immigration, America-first policies has been through a systematic crackdown on the H-1B program. Here is an overview of some of the changes the administration has made since Trump’s election in 2016:

The application process for the H-1B has become even more stringent. This is evidenced by an uptick of “requests for evidence” (RFEs) since 2015—additional proof requested by USCIS of an employee’s eligibility for the visa. H-1B denial rates have leapt for outsourcing and consulting firms in particular.

The Trump administration’s targeting of foreign workers ramped up during the coronavirus pandemic and ahead of November’s presidential elections. Citing the need to protect American jobs, on June 22, the White House issued an executive order temporarily banning the issuance of several visa categories, including the H-1B.

Then, on Oct. 6, the administration announced substantial changes to the program when it reopens, including raising the minimum required wage levels, and shortening the length of visas for some contract workers. The new rules would have disqualified a third of the visa applicants in recent years, by some estimates.

“Certainly, this was a political maneuver by the Trump administration consistent with its rallying cry of saving jobs for Americans,” said Weinrib.

H-1B visa holders have reacted in ways that are almost American, forming community groups and lobbying their senators—or at least the people who would be their senators if they could vote, despite spending years living and working in the country.

Trump’s moves have also rattled US tech firms, which have benefited greatly from the program. (A 2016 report found that more than 15% of Facebook’s employees were on the H-1B). Companies like Google, Amazon, and Microsoft have been vocal opponents of Trump’s moves.

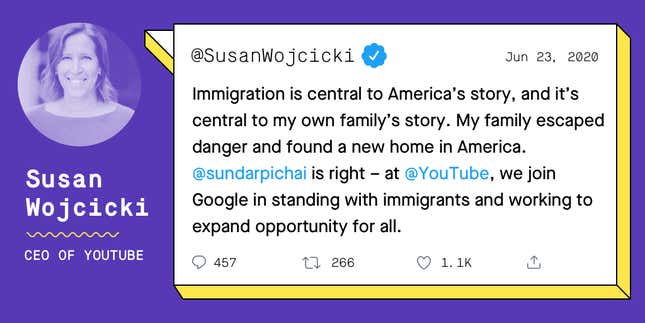

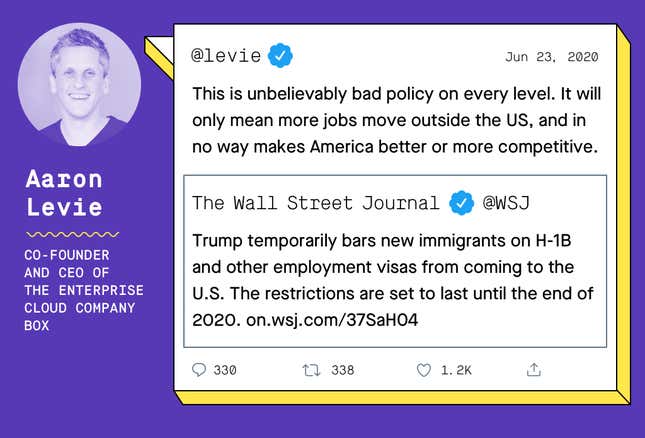

The day after Trump signed his visa ban in June, the response from Silicon Valley was telling:

Shortly after Trump’s latest H-1B pronouncement on Oct. 6, ITServe, an alliance of over 1,400 US tech firms, brought a lawsuit challenging the new rules. It argues that companies would neither be able to absorb the wage hikes nor renegotiate long-term contracts to meet the new guidelines. Several other employers, US universities, and healthcare associations also have also sued the government over its new directive, claiming the rule-making was arbitrary.

The rules “undermine high-skilled immigration in the US and a company’s ability to retain and recruit the very best talent,” said US Chamber CEO Thomas J Donohue.

Critics argue that moves are being done in an attempt to appease voters ahead of a highly contested election. “Why this, why now, and why is it an interim final rule?” said Theresa Cardinal Brown, the director of immigration and cross-border policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center. “There’s no estimate of the amount of jobs this would actually free up for US workers. It’s a bank shot at best.”

The last four years have left many highly skilled professionals fearful of increased scrutiny and sudden major policy changes that could force them to uproot their lives overnight. Some international students say they are discouraged from studying in the US because they have very little hope of getting the opportunity to work in the country after the completion of their courses—one of the main reasons they seek an American education.

“US firms hire directly from US universities, and students make connections and meet recruiters, and get letters of references from US professors,” said Gaurav Khanna, assistant professor at the University of California San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy. “Making it difficult to get a US job lowers these incentives.”

Many of those who once aspired to live the “American dream” are starting to seek opportunities elsewhere. India has benefited a great deal from the program, but there may be upsides to it being restricted as well. A more hostile US immigration policy may encourage talented Indian workers to stay home, or even convince big tech firms to bring some of their operations to India directly.

“If US immigration policy continues on this restrictive path, employers will likely look to relocate jobs in alternative markets where access to high-skilled talent has fewer barriers,” Richard Burke, CEO of immigration and workforce management service firm Envoy Global, told Quartz.

The case for the H-1B

Perhaps one of the biggest arguments in favor of a visa category that brings in high skilled labor is its positive impact on the economy. In the case of the H-1B, the visa has been around long enough for researchers to interrogate the criticism of whether bringing in foreign workers takes away American jobs, or actually contributes to job creation.

Several studies support the latter point. Research conducted by Harvard University in 2013 found that between 1995 and 2008, each high-skilled immigrant worker hired by a firm created 3.1 jobs for US-born workers at that same company. “Having the workers to fill such jobs allows American employers to continue basing individual operations or offices in the US, a move that creates jobs at all levels—from the engineers and computer programmers based in American offices to the secretaries, HR staff, and mailroom employees that support them,” the research noted.

Foreign-born innovators and the companies and technologies they create can also result in job opportunities for American workers. Between 1995 and 2005, immigrants founded 52% of Silicon Valley startups, according to the Immigration Policy Center, the research and policy arm of the American Immigration Council (AIC), a pro-immigration group.

A recent estimate by AIC says that an increase in the H-1B visa cap could create an estimated 1.3 million new jobs and add around $158 billion to America’s gross domestic product by 2045.

New American Economy, a bipartisan immigration advocacy group, posited that rejecting 178,000 H-1B applications in computer-related fields in the lotteries in 2007 and 2008 slowed down the growth of the tech industry in US metropolitan areas. Approving the applications could have created as many as 231,224 tech jobs for local workers in the two years that followed, the group estimates.

An analysis by the National Bureau of Economic Research of 219 American cities between 1990 and 2010 found that the introduction of H-1B STEM workers was associated with a significant increase in wages for college-educated and non-college-educated native workers.

Moreover, unemployment rates in occupations with a large number of H-1B workers tend to be low, suggesting they are filling a skills gap and not just supplanting American workers.

Proponents of the program also say that Americans benefit from the fact that foreign worekrs contribute billions of dollars in tax, as well as Social Security and Medicare, to the benefit of all.

Making the H-1B process so demanding, and keeping the number of visas permitted annually so low is short-sighted, argues Eric Welsh, a partner at Reeves Immigration Law Group. “(It) may satisfy the short-term desire of incentivizing employers to stick to the domestic applicant pool, but long term, those businesses are not getting the best and the brightest,” Welsh said. “If US businesses can’t recruit those highly qualified foreign workers, they are handicapped in the global market, and they will be providing inferior goods and services in the local market.”

Welsh adds that the visa doesn’t only benefit big tech, but firms of all sizes and in all industries.

The US’s battle with the coronavirus pandemic is one example of the positive impact of H-1B workers. Eight companies that are currently trying to develop a coronavirus vaccine in the US together received approvals for 3,310 biochemists, biophysicists, chemists, and other scientists through the H-1B program between 2010 and 2019, according to the American Immigration Council.

“As with many facets of American government and policymaking, it can sometimes be hard to see the forest and not the trees,” the policy reform non-profit Ideal Immigration has argued. “For every situation where the lines get blurred between reality and perception about why a worker was laid off, there are thousands more stories of immigrants filling in employment gaps that make a beneficial contribution to the US economy.”

The need for reform

Several experts believe that there is a need to reform the H-1B program in a more constructive way than Trump’s extreme measures.

The program “has resulted in abuses—and in many cases the displacement—of US workers,” writes Sarah Pierce, a policy analyst for the Policy Migration Institute. “Yet there are smart, implementable fixes that can be made to prevent such abuses and repoint the H-1B program in ways that would go much further toward advancing US economic and competitiveness interests—to the benefit of US workers—than the broad and blunt reforms advanced by the administration.”

Another approach could be to transition H-1B workers to another status before permanent residency, which would give them more security and assurance. “Building a more fair, sustainable path for talented people to evolve to another better, more secure visa even before getting a green card is very necessary,” said Ran Harnevo, the CEO of Homeis, a one-stop-shop for ex-pats in the US.

One of the biggest criticisms is that the computer-run lottery-based system unfairly prizes luck over merit, and the Trump administration has proposed scrapping it in favor of a wage-based system.

Experts at the Atlantic Council, a US-based think tank, believe the lottery should be replaced with a system that allocates visas to the highest-salaried workers or by ranking skill levels. Educational backgrounds could also be incorporated into the decision-making process.

“Virtually any white-collar occupation is eligible for the H-1B program, and the workers need not possess any special skills to qualify to fill an H-1B slot,” the think tank writes. “Visas should be allocated to the best and brightest first.” It also calls for stricter rules around monitoring H-1B abuse.

In the meantime, immigrants may start looking to other US visa categories, which grant citizenship based on business ownership or investment. However, these visas are not viable options for all deserving skilled professionals given that they require shelling out anywhere between $100,000 to $900,000, and may also be subject to future review by a future administration.

Bipartisan legislation to reform the H-1B has been introduced and stalled. While Biden’s win is a signal that more progressive legislation can be expected, much will depend on what his administration is able to get through the Congress.

A referendum on foreign workers

Joe Biden’s win was the more optimistic outcome for H-1B holders and aspirants.

When Biden was vice president under Barack Obama, the White House offered some relief to H-1B aspirants and visa-holders. It extended a short-term work visa for STEM graduates, giving them some extra time in the US before having to apply for the H-1B. Obama also introduced work permits for spouses of H-1B visa holders who were in line for the green card. This was a big relief for thousands of well-educated and skilled dependents, who had been previously unable to work and were trapped in so-called “golden cages” for years.

Biden has made a number of promises on immigration, including reforming rules for foreign workers. He has pledged to do away with country caps on the green card and increase the number of employment-based visas issued each year, except during times of high US employment.

He has also pledged to make it easier for graduates of STEM programs, and doctoral students, to stay and work in the country. “Losing these highly trained workers to foreign economies is a disservice to our own economic competitiveness,” his policy paper states.

But Biden can’t fully dictate the terms. “Much would depend on the makeup of Congress after the election,” said Mark Davies, global chairman at global immigration-focused law firm Davies & Associates, “as well as public opinion in the aftermath of Covid.”

The H-1B may be old and flawed, but it still remains the main vehicle for foreign-born talent to enter the US. In many ways, the upcoming election was a referendum on whether US citizens felt that they benefit from that foreign talent, or not. Now it’s up to the US government to find a path forward.

This story has been updated with the results of the 2020 US election.