Why the US government once sued a Nevada casino over a 14-pound solid gold rooster

On a blazing hot afternoon in July 1960, three armed US marshals raided a casino lobby in Sparks, Nevada, and proceeded to seize a golden statue of a rooster. Invited onlookers jeered and hissed as the agents confiscated the statue, whose attorney decried a “colossal miscarriage of justice.”

On a blazing hot afternoon in July 1960, three armed US marshals raided a casino lobby in Sparks, Nevada, and proceeded to seize a golden statue of a rooster. Invited onlookers jeered and hissed as the agents confiscated the statue, whose attorney decried a “colossal miscarriage of justice.”

The renegade fowl in question was a nine-and-a-half-inch-tall, 14-pound bird made of solid 18-karat gold. Prior to his arrest, his preferred roost had been in a lighted glass display case at the Nugget Casino in Sparks, Nevada, where he had taken up residence in 1958, helping to promote The Golden Rooster Room, a newly opened restaurant at the fast-growing Nugget, which served fried chicken as its signature dish. The metal bird was now a defendant in a Federal complaint brought by Treasury Department, entitled United States of America v. One Solid Gold Object in Form of a Rooster.

Unbeknownst to the bird, he had become the latest–and most severe–action taken by a federal government that was terrified of running out of gold. Since 1933, it had been illegal for most Americans to hold gold in any form except jewelry and tooth fillings. And in the late 1950s, the US government discovered it had a gold problem. Although it held far more of the yellow metal than any other entity in the world, it didn’t, for contemporary purposes, have enough. The issue through the middle part of the decade hadn’t been that the United States was physically losing a great deal of gold; the country’s gold stock remained relatively stable through Eisenhower’s first term at between $20 billion and $22 billion. But as the United States imported more goods and services in the postwar boom, governments and companies outside the country rapidly increased their holdings in dollars and US securities, and those holdings represented potential gold redemptions, payable immediately. This category of claims rose from about $8 billion in 1949 to $12.7 billion at the end of 1953, and then to nearly $16.5 billion by the end of 1956. Because federal law required about half of the gold stock to be held in reserve to shore up the dollar, that meant that if all the foreign claims were redeemed at once for gold, the United States would not be able to make all the payments—a scenario that was universally considered a global economic doomsday.

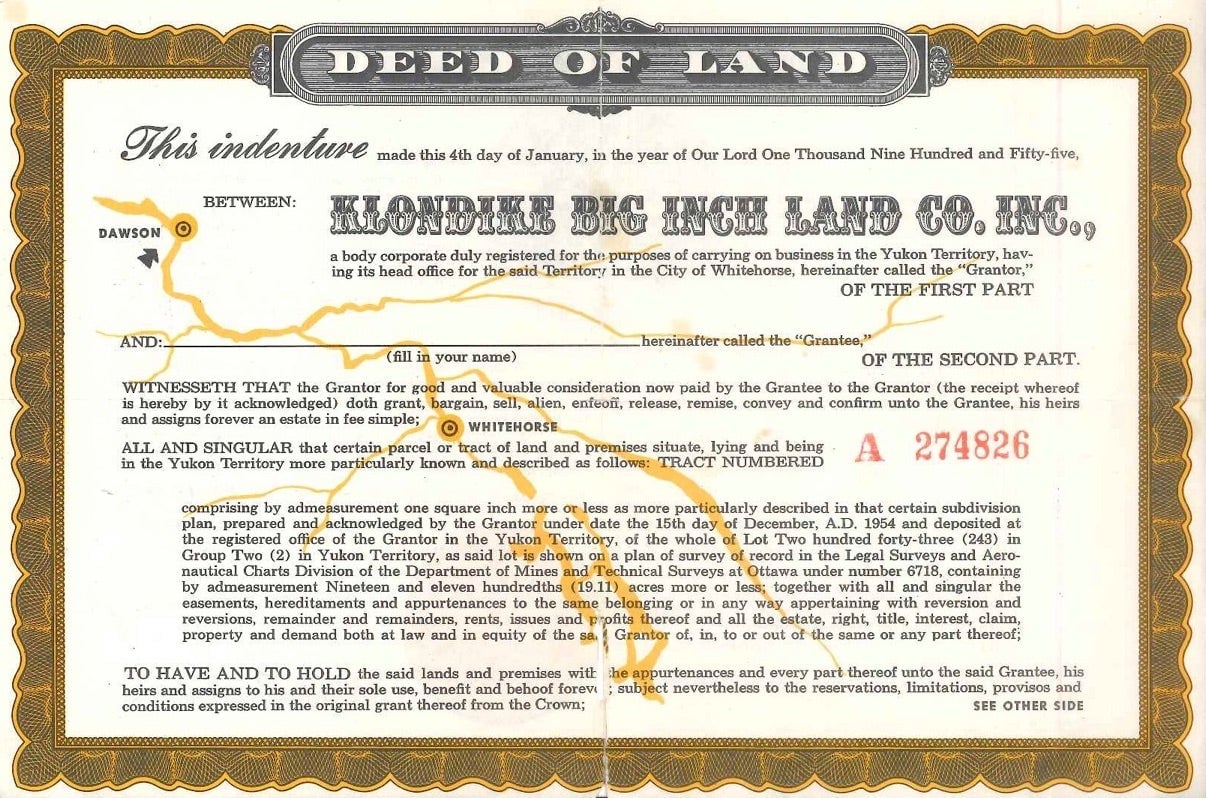

Curiously, the more the US government fretted publicly about the gold supply, the more fascinated the public became. In 1954, an advertising agency working for Quaker Oats hit on an unusual method to promote puffed rice and wheat cereals. To help sponsor the transfer of a popular radio show about Yukon adventures to television, the company purchased 19 acres of land in the Yukon territory for $1,000, near where the turn-of-the-century Klondike Stampede had attracted tens of thousands of would-be miners. With every box of puffed rice or wheat cereal, a customer would receive a “deed of land” to one square inch of land, and presumably to any gold wealth that lay beneath it. Quaker Oats did not anticipate the wild demand or the expense of actually registering 21 million deeds; the “Klondike Big Inch” company went bankrupt and the land was reclaimed by Canada.

Even before the Rooster was sculpted, his legal status was shaky. The idea had been hatched by Richard L. Graves, a street-smart Nevada entrepreneur who loved publicity stunts. Graves began his career in Idaho with restaurants that also featured slot machines, but when Idaho banned slots in the early 1950s, Graves moved his operations south to Nevada. In 1955, when he’d opened the Sparks Nugget, he offered a prize of up to $10,000 for anyone who could sit on top of a flagpole across from his casino for up to a year.

Such gimmicks were designed to lure travelers off Nevada’s Highway 40 to come spend some time and money at the Nugget. To build the rooster, initially, Graves had reached out to Newman’s Silver Shop, a jeweler in Reno, Nevada. They produced a wooden model of the rooster and decided to contact the director of the US Mint in Washington, DC, who quashed the idea of sculpting the rooster. The Mint’s reasoning was straightforward and consistent with many previous rulings: it was illegal for the vast majority of Americans to own that much gold. The exceptions to the law—primarily for a product in which the craftsmanship provided some significant value beyond the value of the metal it contained, and for “customary industrial, professional or artistic uses” of gold—did not seem to apply.

Graves tried to find someone else to craft his shiny bird. With an eye toward the law’s exception for artistic use, he commissioned Frank Polk, a thick-eyebrowed cowboy-turned-artist, to model the rooster. Polk was best known among casino crowds for kitschy slot machines that rendered literal the nickname “one-armed bandits”: life-sized statues of a black-hatted desperado with a pistol-holding arm, which gamblers pulled down to make the wheels on the bandit’s chest spin. Not terribly enthusiastic about the rooster project—Polk quipped, “all I ever did with chickens was eat ’em”—Polk charged only $50 for the design, a few days’ work. Graves had neglected to tell him that the final statue would be solid gold.

To cast the statue, Graves now turned to a downtown San Francisco jeweler called Shreve & Company, a firm with a past rooted in California’s Gold Rush with a license to cast up to 300 ounces of gold. A Shreve official sought and received permission from the superintendent of the San Francisco Mint to cast the casino’s prized rooster.

Thus did the rooster move to the Nugget in May 1958, to much public acclaim. But before the year was over, the Secret Service contacted Graves and informed him that his rooster violated the 1934 Gold Reserve Act. They demanded a same-day meeting in the US Attorney’s office and suggested that Graves bring an attorney. Graves chose Paul Laxalt, an up-and-coming lawyer who’d married the daughter of a prominent Carson City lawyer and Republican activist. Laxalt’s own political career had already begun to take shape; four years earlier, he’d been elected district attorney of the county surrounding Carson City, and by the time the rooster saga was complete, was well on his way to being elected Nevada’s lieutenant governor. From early days, Laxalt’s political identity reflected the western states’ infatuation with gold. One of his campaign television spots featured a miner panning for gold at the side of a river; he turned to the camera to show the phrase “Laxalt for Lt. Governor” shimmering at the bottom of his pan.

Laxalt and Graves explained to the Treasury officials that Shreve & Co. had obtained permission to make the rooster and considered the matter closed. But eighteen months later, in July 1960, the US government, which at the time was tussling with Nevada’s gaming industry as well as watching the outflow of gold, let its disapproval be known. They issued a warrant for the rooster’s arrest, and that was when the US marshals arrived at the Nugget.

Increasingly such heavy-handed actions were at odds with a growing public desire to buy gold for jewelry and investment purposes alike. Some were speculators betting that sooner or later the dollar-gold exchange rate–fixed by the Bretton Woods agreement in 1944 at $35 an ounce–would change in their favor; some wanted an ultraconservative investment, perhaps balancing out a portfolio with more aggressive holdings; some may have seen gold as insurance against a semi-apocalyptic crash of governments and finance predicted by right-wing newsletters since the Roosevelt days. Regardless of motivation, the gold buyers of the late 1950s represented the adventurous edge of a population that was beginning to romanticize gold ownership, and indeed advocate it.

Even Treasury and law enforcement officials seemed to question whether every instance of private gold ownership would genuinely cause the world’s financial sky to fall. For decades, the government fought with an order of nuns in Indianapolis known as the Carmelite sisters. These nuns had proposed in the late 1920s to collect scrap gold—rings, bracelets, old coins—from the faithful and melt it down to create a sacred vessel called a monstrance. Treasury officials blocked their efforts, but the sisters, ever hopeful that the government would one day change its mind, continued to plead their case through the 1960s, all the while amassing gold in small amounts. When they finally relented—in 1970—Treasury authorized a firm to buy the 6 pounds of gold they had collected. An exasperated department veteran explained to his newly appointed boss: “After years of fruitless (and ridiculous) attempts to persuade the nuns to give up their project, the Treasury’s General Counsel made an informal decision to drop the whole matter. All of those originally involved are long since dead. In view of the Treasury’s past dilatory actions, I do not think it either just or politically wise to assess a $1200 penalty on these people at this late stage. They have already lost more than that in foregone interest.”

But few cases were as dramatic and as public as the Golden Rooster. After his arrest, the rooster was confiscated and transferred to a federal bank vault in California. Laxalt swiftly applied for bail for the statue, but was denied; the rooster had to stay incarcerated until trial. Graves, never one to miss a publicity opportunity, placed a bronze replica of the rooster in the case outside the restaurant—dressed in prison stripes.

The golden bird stayed locked up for nearly two years, until his trial by jury began in March 1962. If the government prevailed, the rooster would pay the ultimate price: he would be melted down and stored with the rest of the federal government’s gold reserves. Much of the trial testimony focused on the question of whether or not the Golden Rooster qualified as a work of art, not usually considered an area of Treasury’s expertise. Technically the government conceded that it was art, but maintained that because it was being used for advertising purposes, the rooster was primarily an instrument of commerce. Art critics from Denver and New York were flown into Carson City to meditate on the nature of statuary, and whether emphasizing the gold content of a statue enhanced or detracted from its customary, artistic value. During the trial one critic deemed the bird “exquisite,” while the government’s attorney, Thomas Wilson, got into an argument with the judge about whether it was more common for statues to be solid or hollow.

Wilson also contended that the metal bird was a threat to the American economy, and even to law and order. He told the jury that Graves’s end run around the federal government’s explicit rejection of his initial sculpture plan “makes a mockery of both the law and the country’s attempt to control the gold problem and preserve our monetary basis.” Lest the jury doubt the severity of the Golden Rooster precedent, Wilson spelled it out in his closing argument, using some foreboding (and, at this stage in the trial, hard-to-verify) mathematics. “Our gold reserves have to be 25% of the amount of money outstanding if our money is going to have any stability at all,” he warned. “If one out of 180 people is entitled to make a gold object like that, it brings the gold down below the 25% requirement—and the result of that is economic chaos.”

Ignoring the unlikely scenario of a million golden roosters glimmering across America, Laxalt framed the tale of the Golden Rooster as a retelling of David and Goliath, with the role of Goliath played by a large and bumbling federal government. Yes, the rooster was a work of art created at considerable expense, but he maintained there was a “symbolic value,” which he spelled out: “It is rewarding to feel, people, that any one of us, whether we are big, small, important, unimportant, still have the right under our Constitution, under our laws, to disagree with a Government official.” He made it sound as if it was a Nevadan’s birthright to own and work with gold, and flattered the local jurors’ wisdom and ability to send a message back east. “It is refreshing to me,” Laxalt said, “to see people like Dick Graves who will say to themselves, ‘I still have rights under the Constitution, under the law a Government official can still be wrong, and I can have this problem resolved by a jury, not by some group in Washington who don’t know me or anything about me or the manner in which I live or the manner in which Nevadans live, not by them, but twelve people such as yourselves who live in our area, know the customs of the people and the people involved, and who will come up with a good decision.’” As if to demonstrate the unfeeling nature of the federal government, Laxalt encouraged the jury to consider the fate of the innocent statue should the jury find for his opponent: “It would be a terrible shame to see this rooster confiscated, melted down and put into the gold stocks at Fort Knox.”

Laxalt’s persuasive powers with Nevadans won the day. The jury deliberated for an afternoon and evening, came back the next day and delivered a unanimous verdict in favor of the rooster—and seven months later, Laxalt was elected Nevada’s lieutenant governor—and not long thereafter, governor, and then US senator. Laxalt’s rise represented a new era of American politicians—more conservative, more western-oriented, and with a free gold market at the top of their agenda.