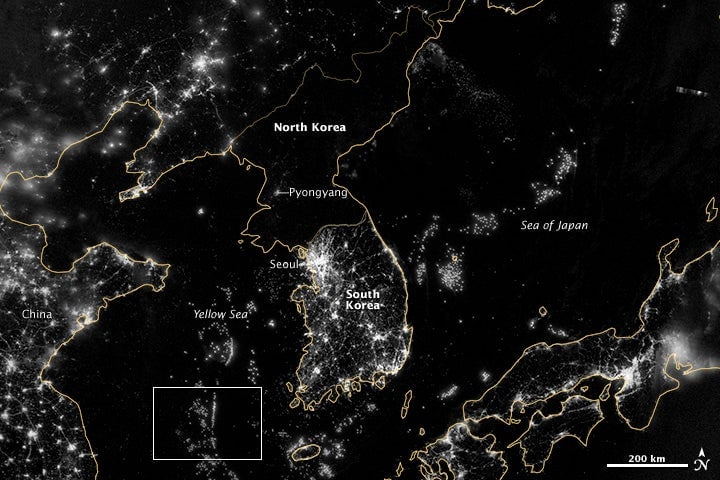

North Korea is sitting on trillions of dollars of untapped wealth, and its neighbors want in

Few think of North Korea as being a prosperous nation. But it is rich in one regard: mineral resources.

Few think of North Korea as being a prosperous nation. But it is rich in one regard: mineral resources.

Currently North Korea is alarming neighbors with its frequent missile tests, and the US with its attempts to field long-range nuclear missiles that can hit American cities. A sixth nuclear test could be imminent. An attack on the US or its allies would be suicidal, so Pyongyang probably aims to extract “aid” from the international community in exchange for dismantling some of its weaponry—rewind about 10 years to see the last time it pulled off the old “nuclear blackmail” trick.

But however much North Korea could extract from other nations that way, the result would pale in comparison to the value of its largely untapped underground resources.

Below the nation’s mostly mountainous surface are vast mineral reserves, including iron, gold, magnesite, zinc, copper, limestone, molybdenum, graphite, and more—all told about 200 kinds of minerals. Also present are large amounts of rare earth metals, which factories in nearby countries need to make smartphones and other high-tech products.

Estimates as to the value of the nation’s mineral resources have varied greatly over the years, made difficult by secrecy and lack of access. North Korea itself has made what are likely exaggerated claims about them. According to one estimate from a South Korean state-owned mining company, they’re worth over $6 trillion. Another from a South Korean research institute puts the amount closer to $10 trillion.

State of neglect

North Korea has prioritized its mining sector since the 1970s (pdf, p. 31). But while mining production increased until about 1990—iron ore production peaked in 1985—after that it started to decline. A count in 2012 put the number of mines in the country at about 700 (pdf, p. 2). Many, though, have been poorly run and are in a state of neglect. The nation lacks the equipment, expertise, and even basic infrastructure to properly tap into the jackpot that waits in the ground.

In April, Lloyd R. Vasey, a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, noted that:

North Korean mining production has decreased significantly since the early 1990s. It is likely that the average operational rate of existing mine facilities is below 30 per cent of capacity. There is a shortage of mining equipment and North Korea is unable to purchase new equipment due to its dire economic situation, the energy shortage and the age and generally poor condition of the power grid.

It doesn’t help that private mining is illegal in communist North Korea, as are private enterprises in general (at least technically). Or that the ruling regime, now led by third-generation dictator Kim Jong-un, has been known to, seemingly on a whim, kick out foreign mining companies it’s allowed in, or suddenly change the terms of agreements.

Despite all this, the nation is so blessed with underground resources that mining makes up roughly 14% of the economy.

A “cash cow”

China is the sector’s main customer. Last September, South Korea’s state-run Korea Development Institute said that the mineral trade between North Korea and China remains a “cash cow” for Pyongyang despite UN sanctions, and that it accounted for 54% (paywall) of the North’s total trade volume to China in the first half of 2016. In 2015 China imported $73 million in iron ore from North Korea, and $680,000 worth of zinc in the first quarter of this year.

North Korea has been particularly active in coal mining in recent years. In 2015 China imported about $1 billion worth of coal from North Korea. Coal is especially appealing because it can be mined with relatively simple equipment. Large deposits of the stuff are located near major ports and the border with China, making the nation’s bad transportation infrastructure less of an issue.

For years Chinese buyers have purchased coal from North Korea at far below the market rate. As of last summer, coal shipments to China accounted for about 40% (paywall) of all North Korean exports. But global demand for coal is declining as alternatives like natural gas and renewables gain momentum, and earlier this year Beijing, in line with UN sanctions, began restricting coal imports from its neighbor.

The sanctions game

After North Korea conducted its first nuclear test in 2006, the UN began imposing ever stronger sanctions against it. Last year the nation’s underground resources became a focus. In November 2016, the UN passed a resolution capping North Korea’s coal exports and banning shipments of nickel, copper, zinc, and silver. That followed a resolution in March 2016 banning the export (pdf) of gold, vanadium, titanium, and rare earth metals.

The resolutions targeting the mining sector could hurt the Kim regime. Before they were issued, a 2014 report on the country’s mining sector by the United States Geological Survey noted that (pdf, p. 3), “The mining sector in North Korea is not directly subject to international economic sanctions and is, therefore, the only legal, lucrative source of investment trade available to the country.”

That is no longer the case.

Of course, Pyongyang has grown adept at evading such sanctions, especially through shipping. Glimpses of its covert activities come from occasional interceptions of vessels. Last August Egyptian authorities boarded a ship laden with 2,300 tons (2,087 metric tons) of iron ore heading from North Korea to the Suez Canal (they also found 30,000 rocket-propelled grenades below the ore).

Earlier this year a group of UN experts concluded that North Korea, despite sanctions, continues to export banned minerals. They determined, as well, that North Korea uses another mineral—gold—along with cash to “entirely circumvent the formal financial sector.”

Interested neighbors

Meanwhile China’s overall trade with North Korea actually increased 37.4% (paywall) in the first quarter compared to the same period last year. Its imports of iron ore from North Korea shot up 270% in January and February from a year ago. Coal dropped 51.6%.

North Korea’s neighbors have long had their eyes on its bonanza of mineral wealth. About five years ago China spent some $10 billion on an infrastructure project near the border with North Korea, primarily to give it easier access to the mineral resources. Conveniently North Korea’s largest iron ore deposits, in Musan County, are right by the border. An analysis of satellite images published last October by 38 North, a website affiliated with Johns Hopkins University, showed mining activity was alive and well in the area.

China particularly covets North Korea’s rare earth minerals. Pyongyang knows this. It punished Beijing in March by suspending exports of the metals to China in retaliation for the coal trade restrictions.

Meanwhile Russia, which also shares a (smaller) border with North Korea, in 2014 developed plans to overhaul North Korea’s rail network in exchange for access to the country’s mineral resources. That particular plan lost steam (pdf, p. 8), but the general sentiment is still alive.

But South Korea has its own plans for the mineral resources. It sees them as a way to help pay for reunification (should it finally come to pass), which is expected to take decades and cost hundreds of billions or even trillions of dollars. (Germany knows a few things about that.) Overhauling the North’s decrepit infrastructure, including the aging railway line, will be part of the enormous bill.

In May, South Korea’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport invited companies to submit bids on possible infrastructure projects in North Korea, especially ones regarding the mining sector. It argued that (paywall) the underground resources could “cover the expense of repairing the North’s poor infrastructure.”

It was, of course, jumping the gun a bit. For now South Korea—and the world—is stuck with a bully in the mineral-blessed North.