There’s an easy marketing trick to get people to eat more vegetables

You can’t just call a beet a beet if you want people to actually eat it. You’ve got to say it’s “dynamite” or “twisted.”

You can’t just call a beet a beet if you want people to actually eat it. You’ve got to say it’s “dynamite” or “twisted.”

In a study published June 12 in JAMA Internal Medicine, psychologists from Stanford University found that the way vegetables are labeled affect how much people want them. Diners at self-serve food stations took vegetable dishes more often when they were labeled with decorative language—like “zesty” or “sweet sizzlin”—than when they were marked with a bland name or advertised as simply being healthy.

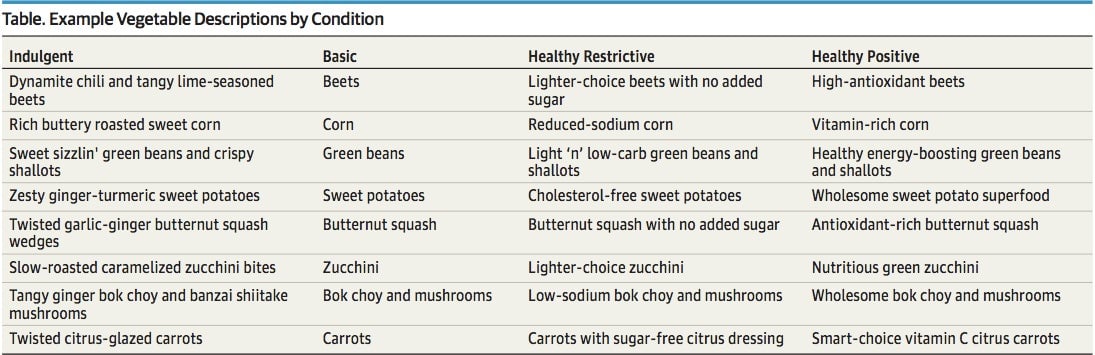

For their work, researchers monitored vegetable dishes served in a Stanford University dining hall during weekdays of the fall 2016 semester. Each day, they changed the language used on labels next to the one of the vegetables being served, moving between four different styles: plain, healthy with a positive spin (e.g., “high in antioxidants”), healthy with a restrictive spin (e.g., “sugar-free”), and decadent.

Researchers tracked how many diners—the majority of which were undergraduates, followed by graduate students, faculty, and other staff—came through and how many of them stopped at the vegetable station each day. They also weighed veggie dishes before and after mealtime to track how much people took.

Of the almost 30,000 diners who visited the cafeteria over the course of 46 days, roughly 8,300 added veggies to their plates. In each case, those vegetable dishes with the “decadent” descriptions outperformed all other labels. People served themselves indulgently labeled foods 25% more often than they did foods with a basic description, 31% more often than foods with a healthy, but positive description, and 41% more often than foods with a healthy, yet restrictive spin. When comparing the weight of vegetables taken from the serving stations, the researchers found that people also took larger portions of the decadently labeled vegetables. Compared to plain-labeled, healthy and positive, and healthy and restrictive labels, people took 16%, 23% and 33% more vegetables (respectively) when they had colorful-language labels.

Although the study couldn’t track how much of these vegetables actually weren’t eaten, previous work has shown that people tend to eat over 90% (paywall) of what they doll out for themselves at self-serve food stations.

“The majority of people prioritize taste over health when deciding what to eat,” says Brad Turnwald, a psychologist at Stanford and lead author of the study. Additionally, most people tend to rate foods that are labeled as nutritious in some way as less tasty or less filling, he says. This is why he thinks more people flocked to “twisted citrus-glazed carrots” or “sweet sizzlin’ green beans and crispy shallots” than “carrots with sugar-free citrus dressing” or “light ‘n’ low-carb green beans and shallots”—or even just “carrots” or “green beans.”

“We suspect that the effects were not just because the words were fancier, but that they evoked specific themes of taste and indulgence that motivated diners to choose them more than the health-labeled vegetables,” says Turnwald.

Because labeling impacts how we expect something to taste, it can be used to trick us into liking things we otherwise wouldn’t. Just last week, researchers from the University of Adelaide in Australia found (paywall) that adding fancy-sounding buzzwords to white wine made drinkers prefer it. This is good if you’re trying to mark up a cheap wine as better than it is, Gizmodo reports, but annoying if you’re selling a high-quality product that’s getting overlooked because of the label.

Turnwald and his team think this work can be used to motivate more people to eat more vegetables while dining out or picking food at the grocery store. “We would encourage restaurants and food service establishments to advertise their healthiest products with more of a focus on the inherent tasty and indulgent properties of the food, rather than focusing on the health properties,” he says.