The only baby book I’m reading while pregnant is this blissfully simple cartoon

My bedside table is typical of someone who’s seven months pregnant, with its ominous stack of at least a dozen books on birth, pregnancy, and motherhood. Some bought, some borrowed. Most unread.

My bedside table is typical of someone who’s seven months pregnant, with its ominous stack of at least a dozen books on birth, pregnancy, and motherhood. Some bought, some borrowed. Most unread.

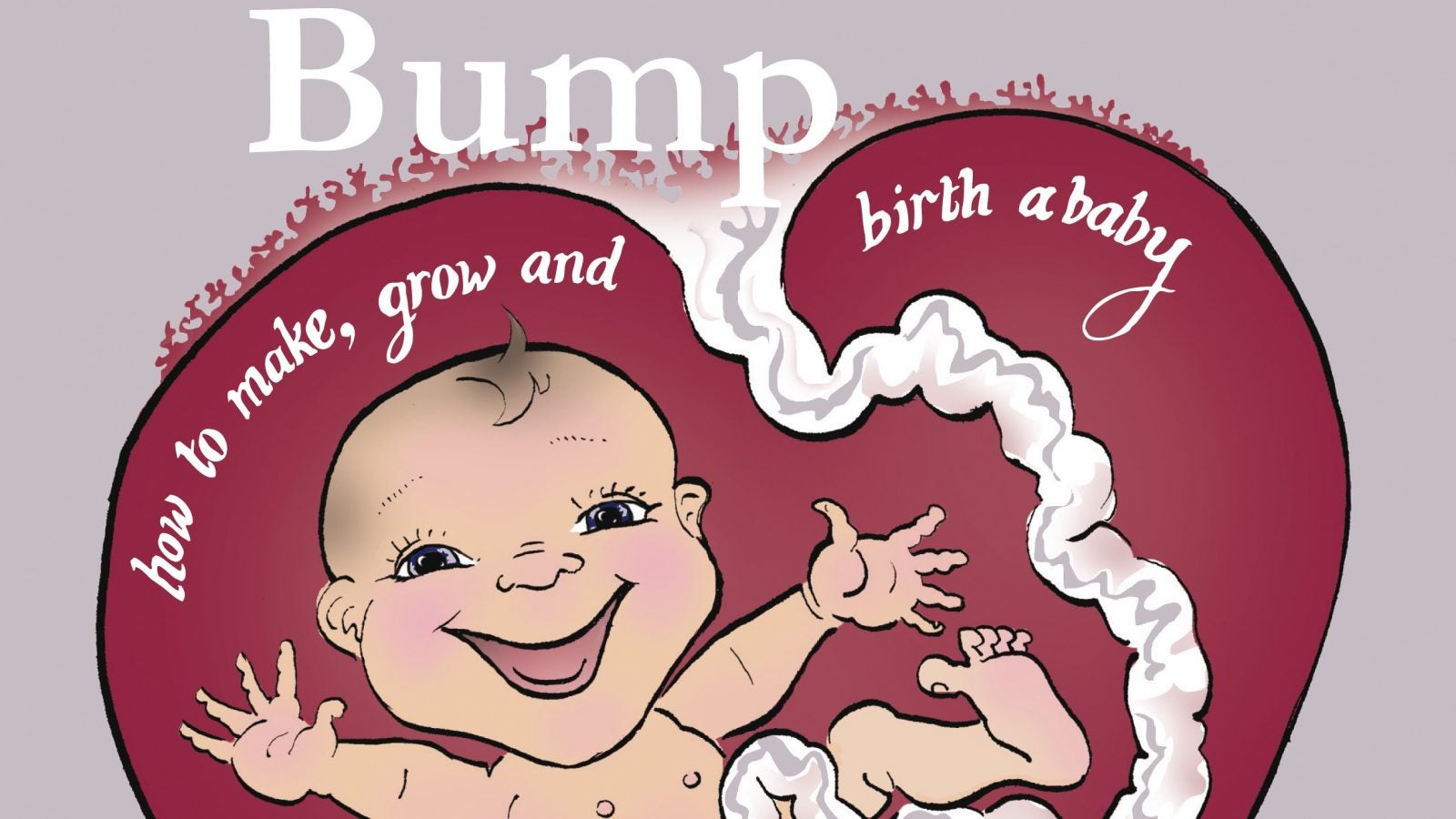

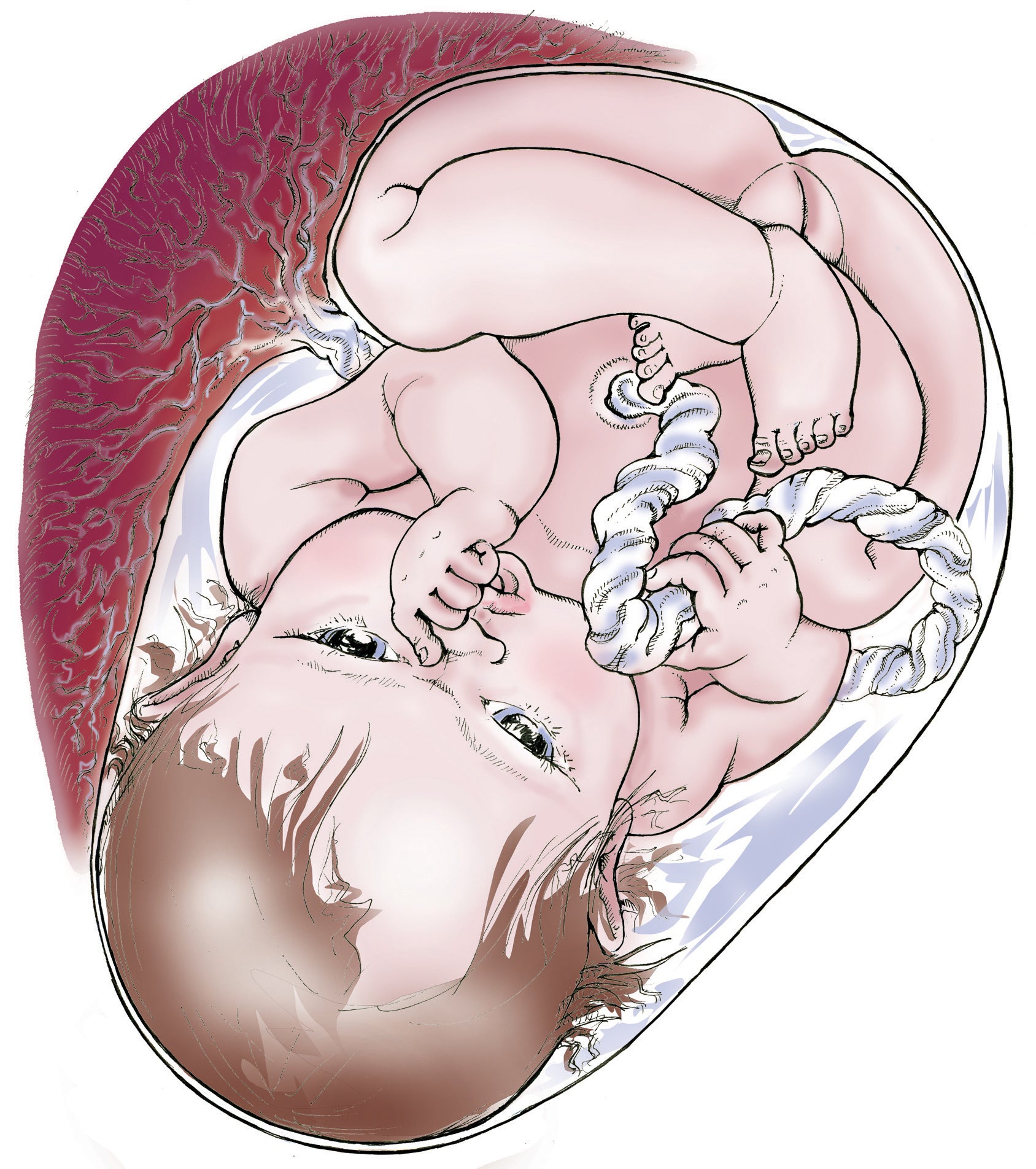

But there’s one book that’s been both pleasurable and quick to read all the way through, and which steers clear of that ubiquitous emotion associated with becoming (and being) a parent: guilt. Bump: How to make, grow, and birth a baby is a choose-your-own adventure cartoon through conception, pregnancy, and birth. The book offers very detailed, visual explanations of bodily processes, mainly through illustrations. What happens to a woman’s body during pregnancy and childbirth—the emergence of the head from the vagina, for example—is easier to stomach through delicate illustrations than gory photographs. That bit of distance that illustrations lend leaves room to contemplate what’s coming, without freaking out.

Just enough information

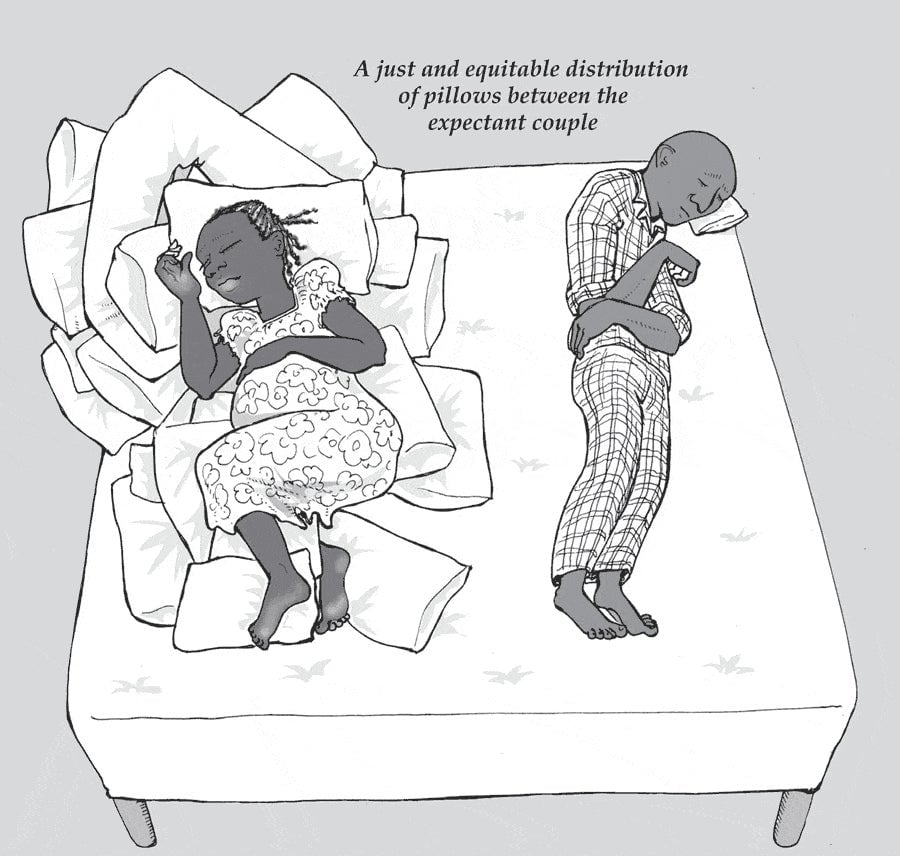

As a cartoonist, author Kate Evans has spent years paring away language to leave only the most essential information, a skill that is painfully lacking in the pregnancy-industrial complex. Bump’s economy means the experience is mercifully finish-able. It employs just enough information, and does so with wisdom and humor. She explains foods to eat and avoid in eight heavily visual pages, a refreshing alternative to the tomes devoted to diet during pregnancy. There are just four-and-a-half pages on “What not to do,” including a section called “Don’t feel guilty.”

The book includes a fair amount of text, too, providing enough detail to feel truly informative. For those who want to dive into more detail, there’s an extensive reference section that cites mainly scientific studies parents can find elsewhere and evaluate for themselves.

Evans is not a medical professional. Instead she draws on her own experience and that of women she’s talked to, backed up by a big body of research. (She also had three professors of midwifery and three trained midwives review Bump before publication).

The work is a complement to her first book about parenting, The Food of Love, a graphic exploration of breastfeeding. It arose from her struggles to breastfeed her first child, coupled with her determination to keep trying. (Her own mother gave birth to and breastfed another daughter when Evans was 13, which the cartoonist says gave her a strong example of its benefits and feasibility.)

Bump was inspired by Evans’s experience of giving birth to her two children. Creating her family wasn’t easy, and she includes a chapter on losing a baby in the book, as well as information on abortion. She had three miscarriages before her first son was born, and three more between his birth and her daughter’s.

Pregnancy politics

Evans acknowledges that women’s fertility is highly politicized. When and how to get pregnant, struggling to conceive, the decision to terminate a pregnancy, miscarriage, how to give birth, breastfeeding, and how to raise children are endlessly hashed out areas of women’s lives. Though she describes herself as an advocate of “natural” birth—meaning vaginal birth without medical intervention like forceps delivery or caesarian section—she didn’t want readers to feel that this path is “something they have to achieve.”

Motherhood is beset with guilt because it’s “not possible to do it right,” she says. “We’ve got conflicting theories on what the right way to have a baby is, and what the right way to raise that baby is,” she continues, and the clash is “quite a destabilizing thing about our society.”

Her illustrations explore the tension between parents’ craving for cultural continuity—the sense that we’re doing what’s been done right before—and their openness to change. In a nod to cultural continuity, Evans’s illustrations for one section on birthing show a baby born in a cottage by a fire, which she describes as the story of “a maiden, a mother, and a crone.” It’s “a primal creation myth,” she says.

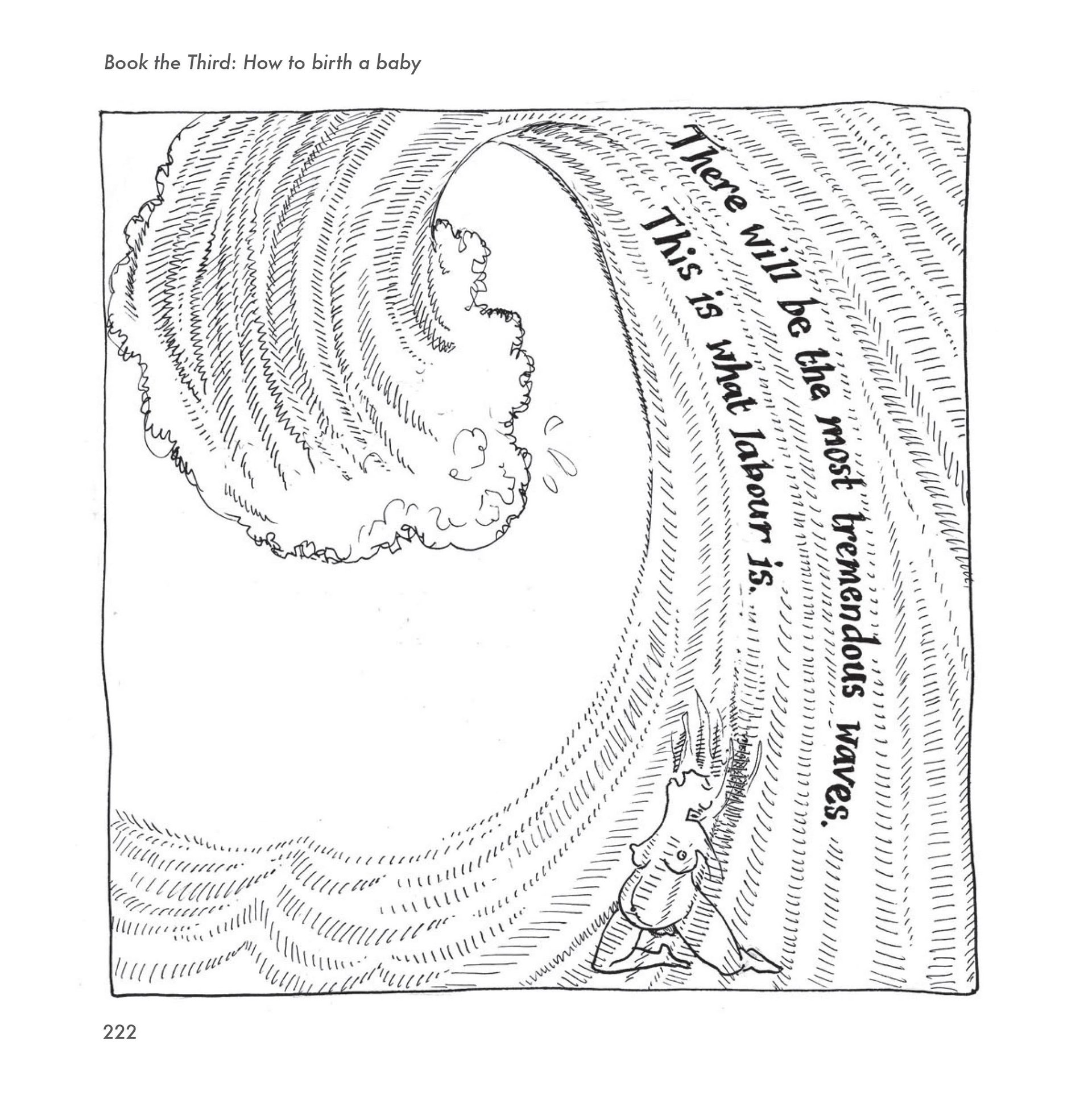

Another birth-related section, Crossing the Sea, is more of a meditation on the awesome power of women in labor, with drawings of a woman swimming and diving through huge ocean waves.

Overcoming fear

Above all, Bump is deeply positive about women’s capacity and strength.

“It’s absolutely awesome, what women can do,” Evans says. “You hear people saying that women’s bodies have a design flaw…That is not the case.” In this way Evans is a clear proponent of the natural birth movement, which centers on the idea that women’s bodies are perfectly designed for the process of birth-giving, and that a lot of the “work” of preparing for birth is in clearing the clutter of fear and medicalization that gets in the way.

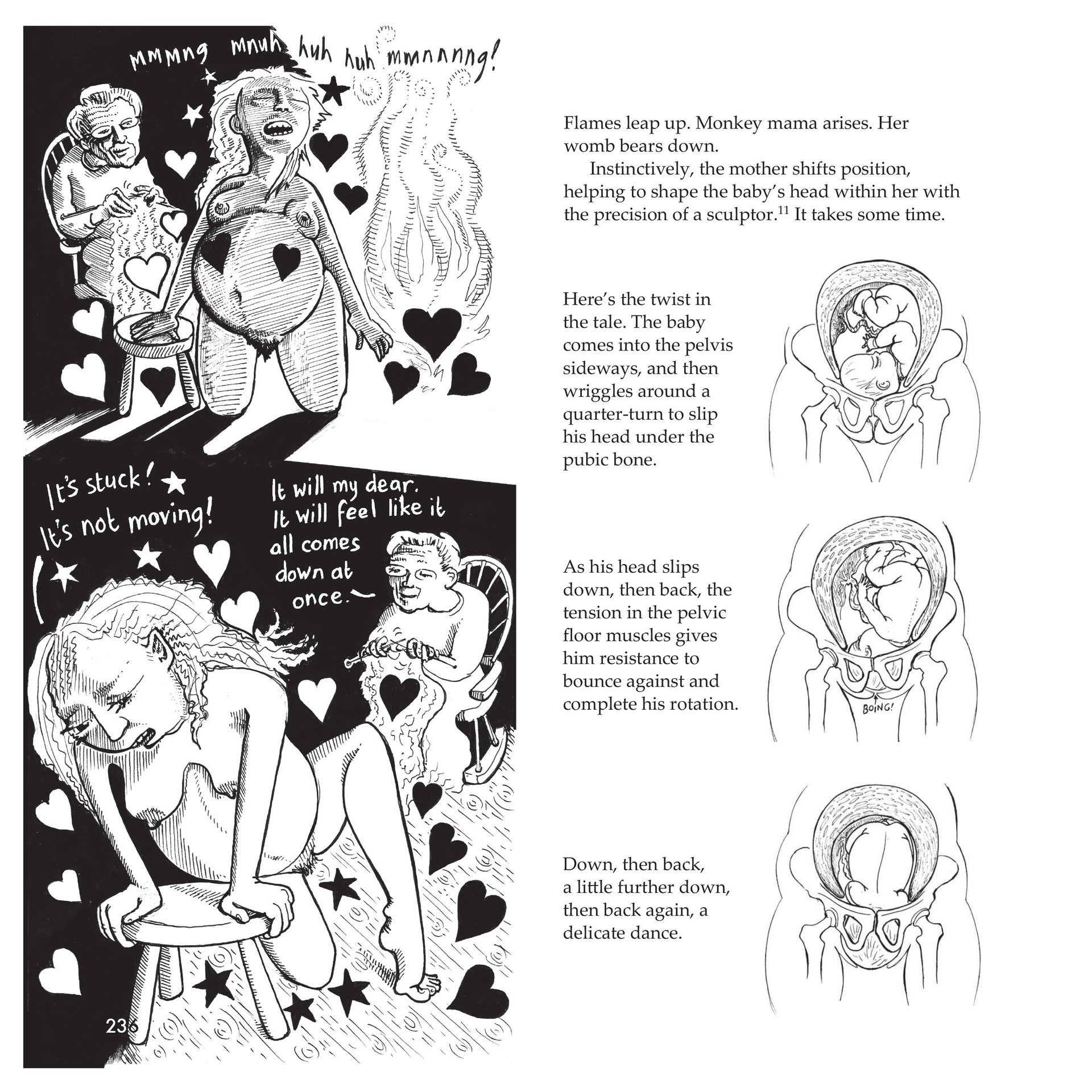

For example, in the book she illustrates a quarter-turn, which most babies make during labour in order to get more easily past the pelvic bone.

The drawing is of a woman’s upright body, a common position in natural birth that aligns the body with gravity. In researching the drawing, the only diagrams Evans could find were of the turn taking place in the body of a woman lying on her back with her legs in the air—a position common to films and TV, but also now widely considered more convenient for medical professionals than for laboring women.

I haven’t given birth yet. But Evans’s perspective gives me more hope that the experience doesn’t have to be focused on pain and fear. Perhaps it can be transcendent.

“Every birth is different, and every woman is different, and every baby is different. But to refuse to acknowledge that birth can be a magnificent and incredible thing is also doing women a massive disservice,” Evans says. “It’s very rarely easy. But then most amazing and awesome and magnificent things in life are not.”