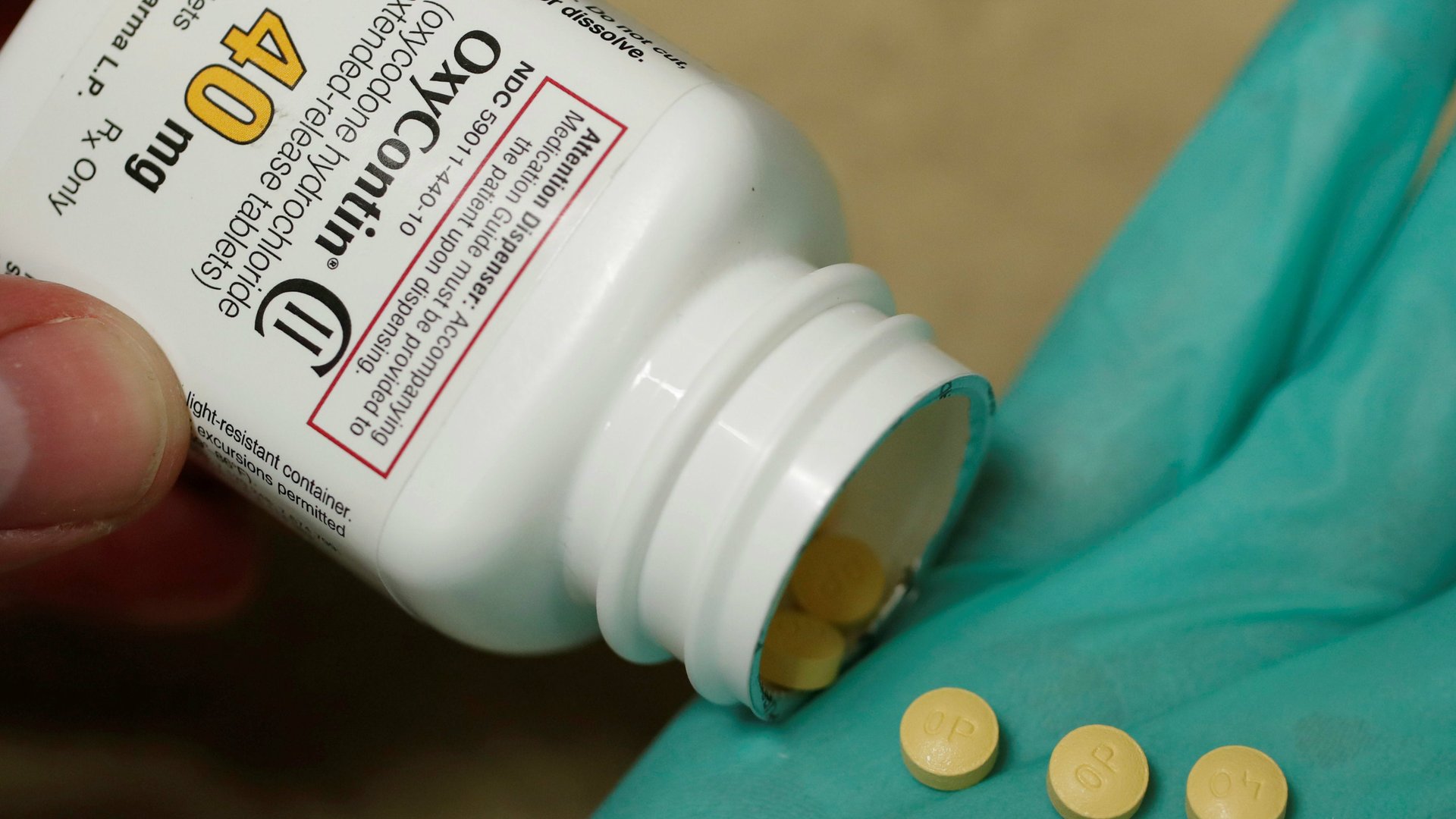

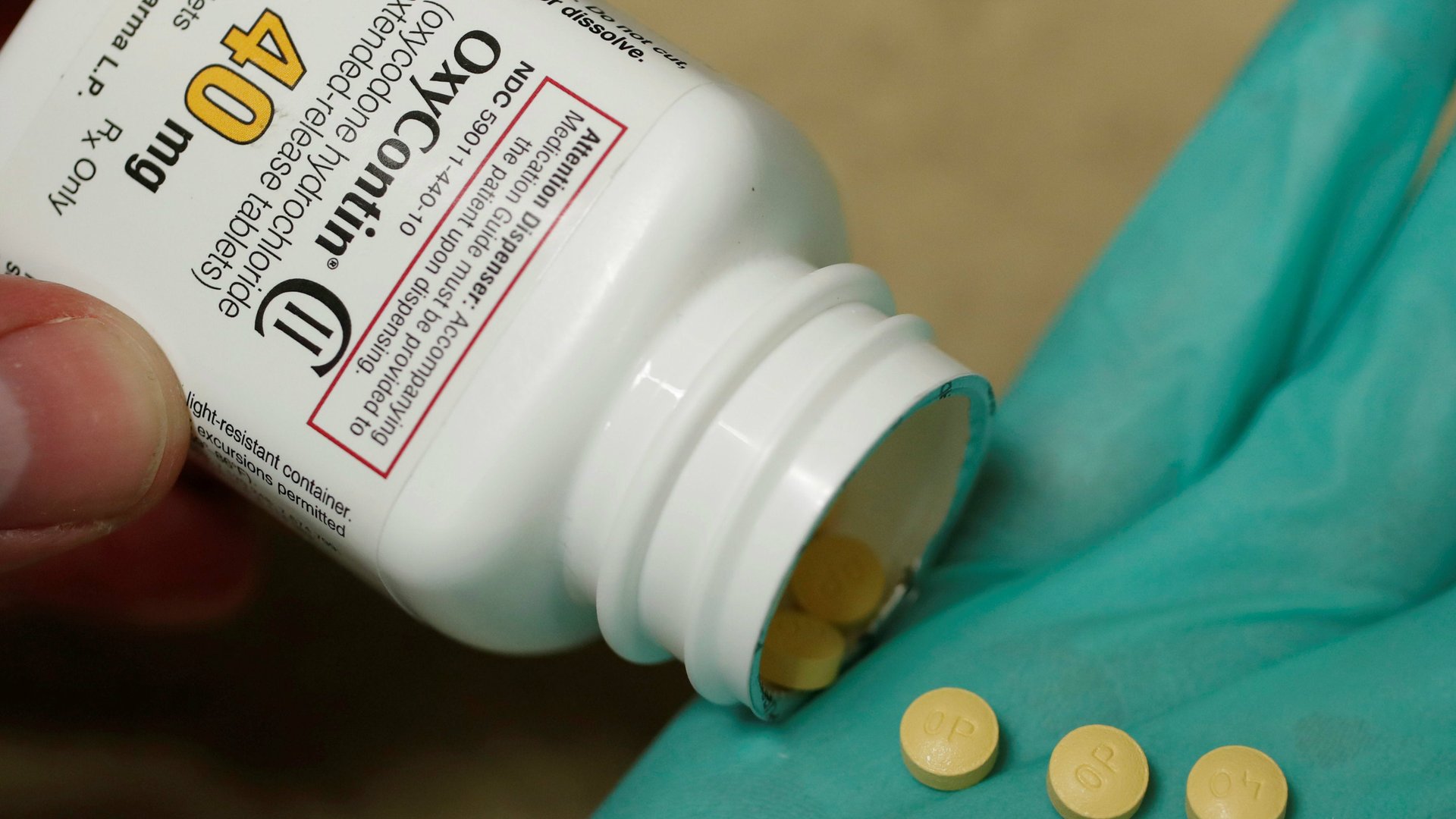

How doctors, the government, and big pharma teamed up to pump Americans full of opioids

In the first five years that OxyContin was on the market, Purdue Frederick, the pharmaceutical company that had launched the drug in 1996, conducted over forty national pain management and speaker training conferences. Physicians who were willing to spread the word could expect to make up to $3,000 for telling their colleagues, often at lavish dinner meetings or continuing education medical seminars, why Oxy worked so well for them. The strategy could not have been more successful; in record time, ordinary musculoskeletal pain, long understood to be a normal part of life, was recast as an enemy to be battled and subdued.

In the first five years that OxyContin was on the market, Purdue Frederick, the pharmaceutical company that had launched the drug in 1996, conducted over forty national pain management and speaker training conferences. Physicians who were willing to spread the word could expect to make up to $3,000 for telling their colleagues, often at lavish dinner meetings or continuing education medical seminars, why Oxy worked so well for them. The strategy could not have been more successful; in record time, ordinary musculoskeletal pain, long understood to be a normal part of life, was recast as an enemy to be battled and subdued.

For decades, physicians had recognized that opioids were highly addictive drugs, and that to prescribe them to any patients other than those who suffered from terminal cancer was illegal. But with Oxy, the tide had turned: suddenly, physicians who allowed patients to “suffer needlessly” from back pain were labeled as lacking in compassion. For general practitioners, who found themselves with “failed” back surgery patients entrusted to their care, OxyContin offered an answer to their prayers.

Purdue marketed the drug aggressively, producing videotapes narrated by a distinguished physician-spokesman that were distributed among 15,000 doctors across the US. Featured on the tape was Oxy patient Johnny Sullivan, who made his pitch from a construction site. Standing beside heavy machinery, which presumably he operated, Sullivan told viewers that he was thrilled to have found a drug that did not turn him into a zombie. Before OxyContin, “even a good day was hell,” he said, but now, his future “looked just great.” Other patients heartily agreed.

By the year 2000, Purdue had doubled the size of its sales force, in an effort to accumulate a roster of 70,000 “committed” physicians who would prescribe OxyContin for the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain. Reps were encouraged, legal records show, to tell doctors that extended-release opioids should be substituted for other analgesics, including short-acting ones like Vicodin. For those reps, who were expected to make about 35 physician calls per week, it was a lucrative business: The average income for a Purdue rep, including bonus, exceeded $120,000 annually.

Purdue’s collateral patient advocate website, positioned as an impartial and valuable patient resource, listed 33,000 physicians who were ready and willing to prescribe opioids. These physicians would provide suitable patients with a starter supply coupon that they could take to the pharmacy for a free 30-day supply of Oxy.

Under pressure not only from the pharmaceutical business, but also from physicians who wanted to be sure they had the federal stamp of approval for this rampant prescribing, the Joint Commission declared pain to be “the fifth vital sign,” adding it to measurements of pulse, blood pressure, core temperature, and respiration. This would turn out to be a grave error. The standard vital signs were readily quantified—either they were normal, or they were not—but only the patient could identify his pain level. Nevertheless, the Joint Commission directed all accredited US hospitals and health care facilities to instruct personnel to monitor pain and to provide compassionate care. In the Joint Commission’s monograph, published in 2001, the organization noted that “in general, patients in pain do not become addicted to opioids.”

Even the DEA climbed on board, signing an agreement with 21 medical professional societies that allowed doctors to prescribe the drugs without fear of prosecution. If physicians had lingering doubts, and some did, these were dispelled in president Bill Clinton’s last weeks in office, when he signed legislation declaring the upcoming decade, 2000 to 2010, to be the Decade of Pain Control and Research.

For a long while, it was understood that opioid addiction was the outcome of misuse or abuse, and was unrelated to doctors’ prescribing habits. “The reality is that the vast majority of people who are given these medications by doctors will not become addicted,” pain physician and Purdue spokesman Russell Portenoy told those who assembled for a media gathering at a DC press conference. Repeatedly, Purdue described a “bright line” between the state of addiction and that of physical dependence in the treatment of chronic pain. For patients who needed pain control, Purdue said, access to chronic opioid therapy was really no different from providing insulin to a diabetic.

Some regarded that comparison as outrageous. Andrew Kolodny, at the time an addiction psychiatrist at Maimonides Medical Center in New York City, had founded a group called Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, known as PROP. In 2011, Kolodny presciently explained that the year before, enough painkiller prescriptions had been written and filled to medicate every American adult around the clock for a month. Physicians who overprescribed to patients with non-cancer chronic pain, he insisted, were largely responsible for having created the epidemic of addiction, not only to prescribed opioids, but also to heroin. Government policy makers at the FDA puzzled over this notion of physician-prescribed addiction, but did little to slow it. Within the next several years, the cost of prescription painkillers would reach $18 billion annually in the US. There would be 92,000 opioid poisoning visits to hospital emergency rooms at a national cost of about $1.4 billion, and nearly 19,000 overdose deaths. Several other nations, including Canada and the UK, would also find themselves in the grip of a prescription-driven public health crisis.

In the wake of this carnage, research groups like the Cochrane Collaboration stated that they could find no clinically significant benefit for opioids over NSAIDs like naproxen—the over-the-counter medicine commonly sold as Aleve. An investigation in the United Kingdom would reveal that patients who were prescribed daily opioids for chronic pain were more disabled at the study’s six-month follow-up than they were before they began taking the drugs. A Scandinavian study complemented those findings, showing that the odds for recovery from chronic pain were almost four times higher for patients who did not take painkillers, compared with those who used opioids. Medical professional societies got on board: The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) told its members that the risks of opioids in the treatment of non-cancer chronic pain patients far outweighed the benefits. If physicians stopped using the drugs to treat such conditions as fibromyalgia, back pain, and headache, the AAN observed, long-term exposure to opioids could decline by as much as 50%.

Johnny Sullivan, Purdue’s poster-boy for Oxy success, would be dead, having fallen asleep at the wheel in 2008 and flipped his truck. His widow explained that she’d known for a long time that her husband was addicted to OxyContin. He fell asleep everywhere, she said, and he’d overdosed several times before he died. “I knew eventually it was going to kill him,” she told psychiatrist Andrew Kolodny. “He might have said he got his life back, but it took his life in the end.”

Adapted from CROOKED. Copyright © 2017 by Cathryn Jakobson Ramin. Reprinted by permission of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Learn how to write for Quartz Ideas. We welcome your comments at [email protected].

Read an interview with CROOKED author Cathryn Jakobson Ramin: The $100 billion per year back pain industry is mostly a hoax