On June 31, 1997, Hong Kong had a taste of independence for just one day

It was June 31, 1997.

It was June 31, 1997.

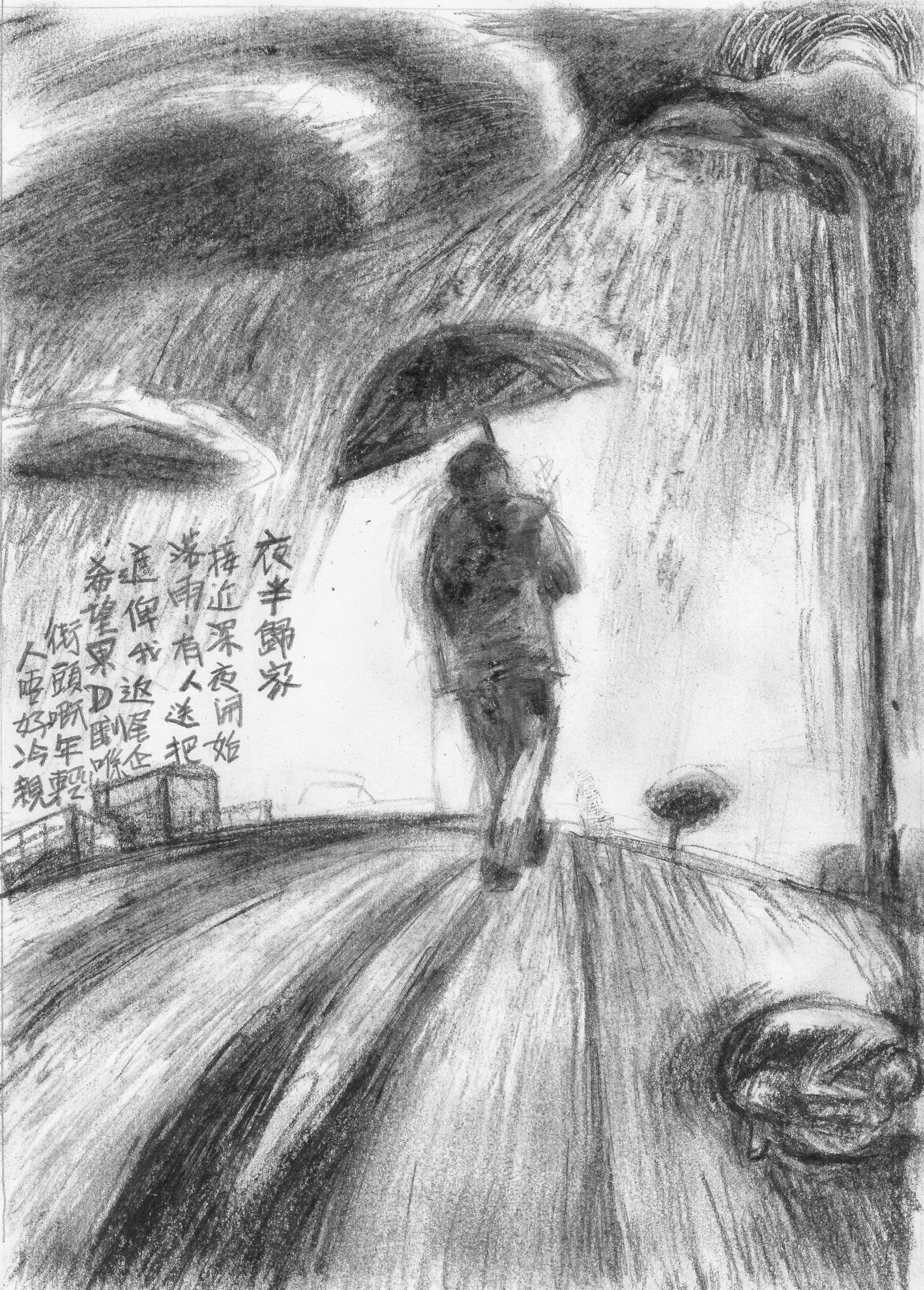

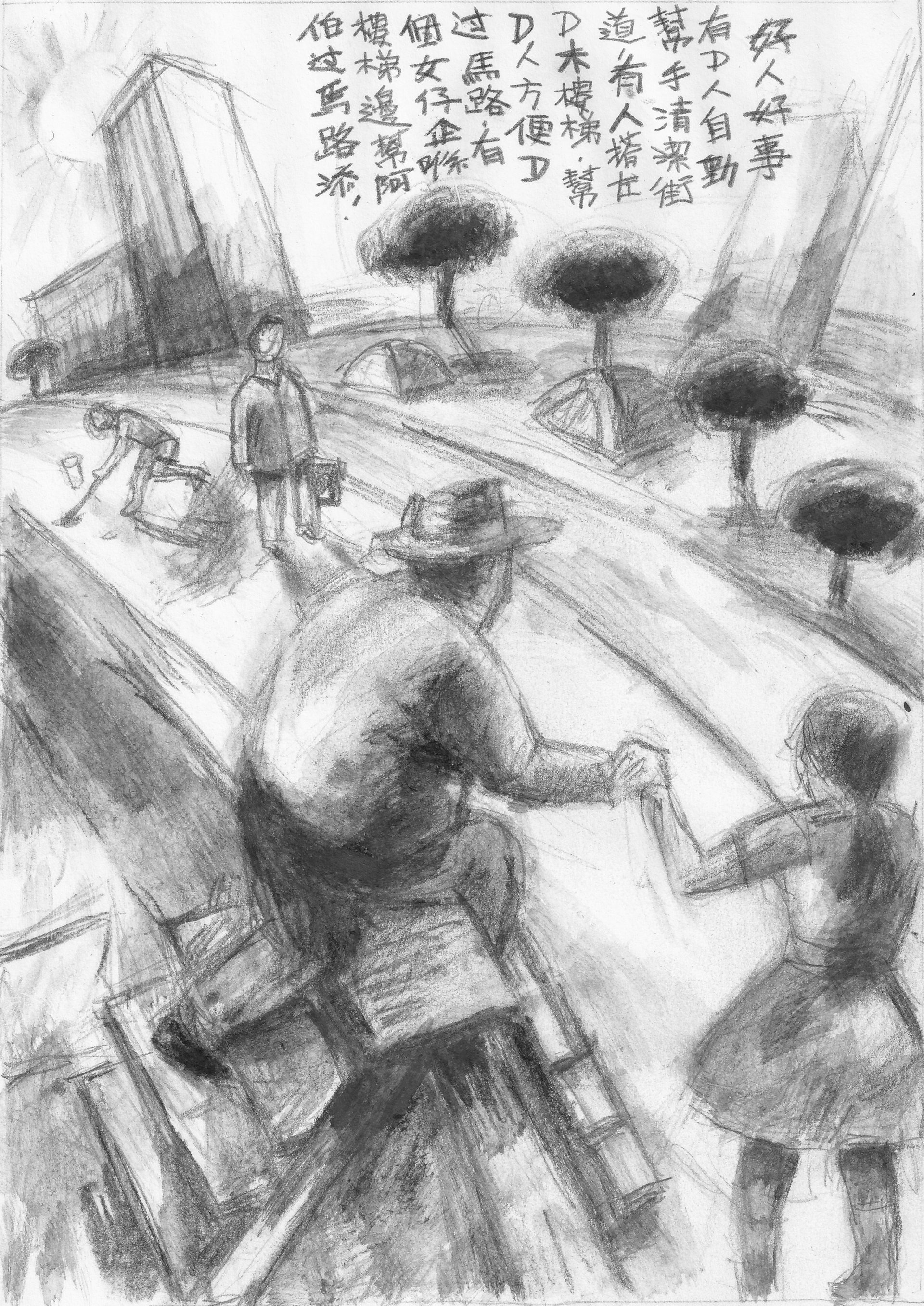

Hong Kong experienced a moment of tranquility it never had before: Strong community spirit was seen as friendly citizens helped out each other unconditionally, the city was in good order, and people were free from worries about their political future. On that very special day, Hong Kong belonged to neither the British nor Chinese.

But June 31 is only an imaginary independence day, existing only in an artistic project by David Clarke. “My goal is to create a space for people to debate what we have become, and how do we feel now when we look back,” says Clarke, who’s been living in Hong Kong since 1986. “When Hong Kong was handed over to China, the city was offered stability and prosperity. But now this has become a broken promise and our society is divided.”

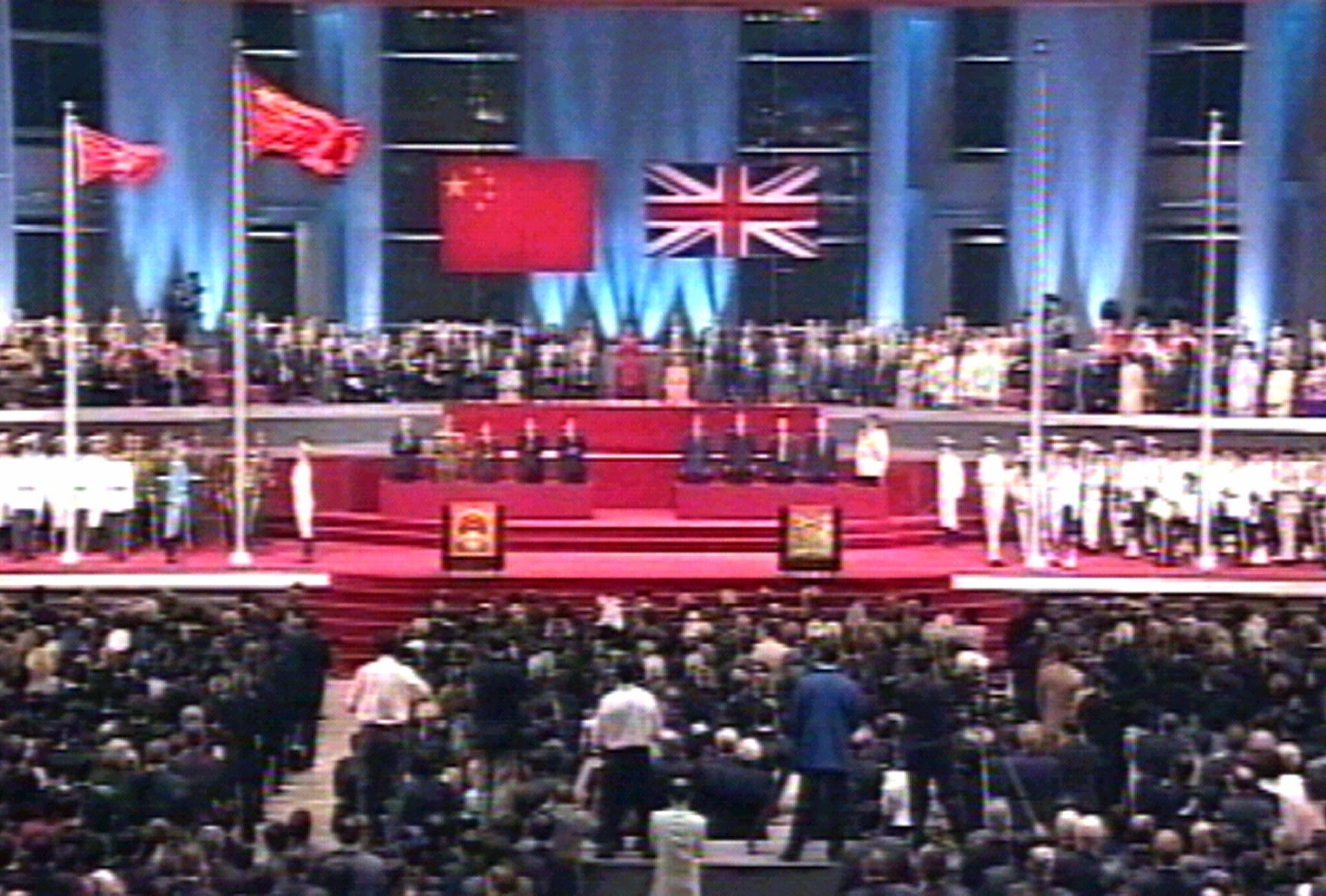

The Hong Kong artist and art historian took the inspiration from a uncomfortable 10-second silence during the handover ceremony 20 years ago. He discovered this brief lull when he examined the official feed of the ceremony. On July 1, 1997, Britain handed the city over to China under the premise of “one country, two systems,” where Hong Kong would retain its freedom and autonomy for 50 years until 2047 as agreed in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration.

“There was a 10-second hiatus between the British and Chinese national anthems during the ceremony,” Clarke says. During the ceremony, the British and Chinese national anthems were played one after the other. In order to avoid any overlapping, the Chinese national anthem was played only after the British one had completely finished, resulting in a 10-second silence.

For Clarke, that marked a brief moment when Hong Kong was independent from the British and the Chinese. But instead of 10 seconds, what would’ve happened if Hong Kong was given a whole day? How would people organize their lives? He posed these questions to the public, asking them to use their imagination to come up with answers for his project June 31 1997.

Clarke’s research results will be on display in an exhibition opening June 29 at Videotage, an independent art space at Cattle Depot Artist Village in Kowloon’s Ma Tau Kok area. The exhibition, curated by Issac Leung, will consist of videos, prints, and wall texts by Clarke, juxtaposed against a series of new drawings from curator and artist Oscar Ho and a piece of short fiction called “The transubstantiation of the ants” by Hong Kong author Xu Xi.

Ten years ago, Clarke deconstructed his memory of the handover through a video of archive images. A decade later, he created a video derived from the last five seconds of that brief silence during the handover ceremony, capturing a close-up of Prince Charles that suggested he was aware of the moment’s awkwardness, according to Clarke. “By slowing these five seconds down, and looping them, I hope to extend or propagate this space without sovereignty, and make it available for inspection,” he says.

Another video Clarke produced captures the transit of space between Hong Kong and Shenzhen immigration points. The video depicts in slow motion the departure from Hong Kong’s border, but viewers never see the arrival in mainland China. To Clarke, it was a spatial equivalent to the in-between space of the 10-second void. The video is accompanied by a soundtrack of Clarke’s interviews with 50 people of their “memories” of June 31, 1997.

Clarke began conducting these interviews five years ago. To his surprise, many people falsely recalled events on the non-existent date, demonstrating the fluidity of memory, constantly shaped by the conditions of the present, says Clarke.

Oscar Ho, Clarke’s long-time friend and collaborator, put his vision of this imaginary day in a series of drawings entitled One Day Paradise. Comprising eight drawings, the series was inspired by the pro-democracy Umbrella Movement in 2014. It was an ideal image of Hong Kong, says Ho.

“Such ideal did exist throughout the 79 days of the Umbrella protests. People were friendly to each other. They were organized and considerate, volunteering to help and support each other whether it was cleaning up the protest sites or tutoring young student protesters. It was the best of Hong Kong I’ve ever seen,” adds Ho. “The experience plays an important role in the identity of Hong Kong. It was the utopia.”

While the independence of June 31 is only hypothetical, the Hong Kong identity still exists 20 years after the handover. In the eyes of the establishment, the strong identity of Hong Kong is seen as a potential threat to communist rule, and as such Hong Kong’s incoming chief executive Carrie Lam has pledged to boost national education among the youth and nurture the sense of Chinese-ness among kindergarten children.

But to Clarke, identity isn’t a static idea that can be cultivated just by making a statement. “The fabrication of identity should not be based on the flag or skin color, but through culture and imagination,” he says. “Arts and culture have a bigger role to play.”

Read Quartz’s complete series on the 20th anniversary of the Hong Kong handover.