Foreign dairy firms are going to have to start helping their Chinese competitors

A week after the Chinese government launched a probe into price-fixing for baby formula, Switzerland’s Nestlé, the Netherlands’ FrieslandCampina and France’s Danone have already bent to pressure (paywall) to lower their prices, as has a leading local manufacturer that wasn’t even named in the original probe. Other foreign companies under investigation—US companies Abbott and Mead Johnson—will probably follow suit. That could hurt some of them considerably. Mead Johnson, for instance, earns 30% of its revenue from China, according to FactSet, though not all of that is from baby formula.

A week after the Chinese government launched a probe into price-fixing for baby formula, Switzerland’s Nestlé, the Netherlands’ FrieslandCampina and France’s Danone have already bent to pressure (paywall) to lower their prices, as has a leading local manufacturer that wasn’t even named in the original probe. Other foreign companies under investigation—US companies Abbott and Mead Johnson—will probably follow suit. That could hurt some of them considerably. Mead Johnson, for instance, earns 30% of its revenue from China, according to FactSet, though not all of that is from baby formula.

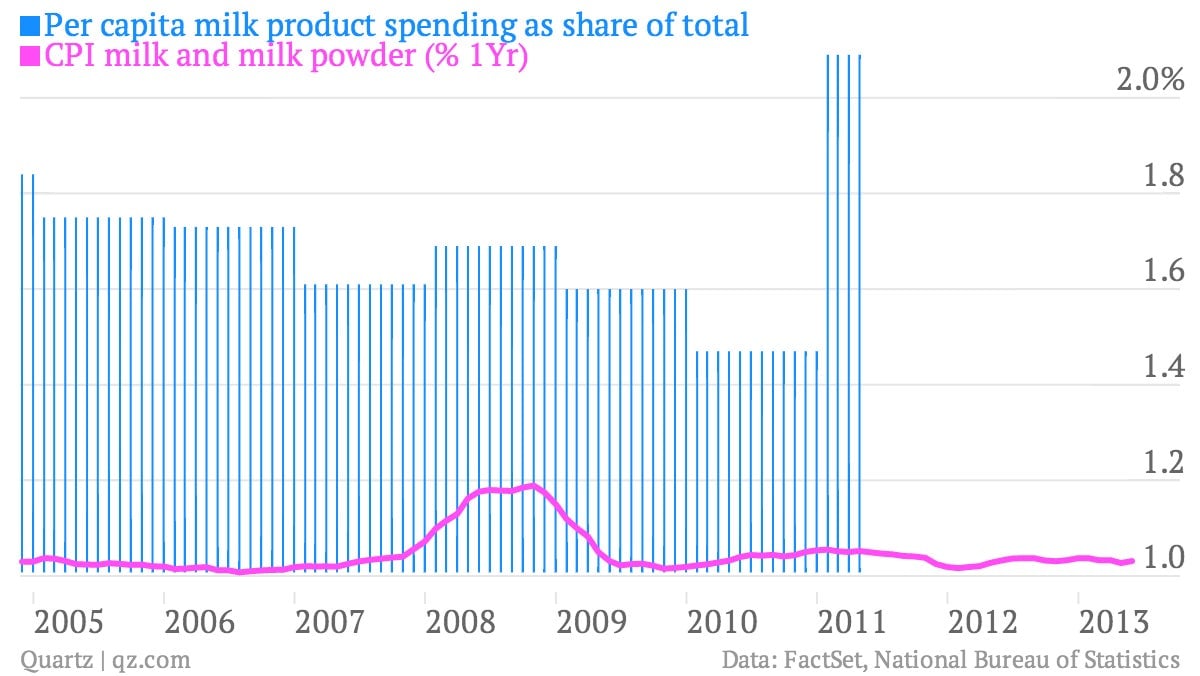

Though the government’s complaint is that milk powder has gone up 30% in price since 2008, when tainted formula killed six babies, this probably isn’t just about price. Though the amount Chinese spent on milk products rose in 2011—just before the government stopped reporting that figure—it was still a tiny percentage of their overall spending. Plus, the consumer price index for milk and milk powder has been stable since 2008:

What the government is really after is “industry consolidation.” This is Chinese Communist Party-speak for squeezing out hard-to-regulate smaller players, while underwriting acquisitions by “national champion” state-owned enterprises. This usually entails a healthy dose of protectionism, such as the newly introduced requirement that producers own their own milk supply (the “national champions” already do).

Expect state-owned China Mengniu Dairy and Inner Mongolia Yili Industry to lead the pack. In fact, they already are. Mengniu, for example, just bought a 27% stake in China Modern Dairy, the country’s biggest producer of raw milk, for 12% less than the market price. That discount could have resulted from government sway with the sellers—private equity groups including the US’s Kohlberg, Kravis & Roberts—which may have received a bigger stake in Mengniu in exchange. Mengniu also took over a $1.6 billion Carlyle stake in infant formula company Yashili International Holdings, which sources exclusively from New Zealand.

But the government also needs to bully foreign brands because, as a retail analyst told Reuters, it must boost consumption of local brands before full-throttle consolidation can begin. That’ll be tough given that consumers don’t trust them. Mengniu, for instance, has faced a spate of safety scandals in recent years. While Yili’s fortunes have been somewhat better, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s clean. The South China Morning Post just reported that Yili’s Gold brand contained 0.6 grams of transfats per 100 grams, a level US regulators deem excessive (paywall).

The subtext of the government’s regulatory hectoring is that foreign companies should do what’s best for China’s dairy industry, not for their bottom lines. This likely means they should partner with national champions, teaching them state-of-the-art quality control, if they want to avoid government hampering at every turn. Those partnerships will help local companies by muddying the distinction between foreign and local brands among consumers.

And if the past is anything to go by, the national champions will turn around and use their new industry know-how and burnished reputations to launch products that compete with their foreign partners, as happened between Danone and Wahaha. But these are the terms; if foreign companies want access to China’s booming dairy market, they must accept them.

Some foreign players are already hip to this. Nestlé is “collaborating with local governments, banks, and investors to accelerate the consolidation of China’s dairy farms,” reports BloombergBusinessweek. And Danone just bought a 4% stake in Mengniu to improve the latter’s infant formula production process (at least it will have a financial stake in its likely future competitor).

But partnerships with foreign firms aren’t the only options for China’s national champions. China’s industry leaders are on a tear overseas. Yili just sewed up a deal with Dairy Farmers of America, an industry-buying association that bargains on behalf of 18,000 US farmers—a potential supply source for Yili—after announcing last December a $180 million investment in a New Zealand-based baby formula project. Wahaha, meanwhile, already sources from the Netherlands, and is looking to lasso Australian herds as well. While the perception among consumers is certainly that foreign-sourced milk is better—tellingly, Nestlé sources all of the milk for its China products domestically except milk powder—whether these overseas supplies will wipe clean the sullied reputations of local firms is unclear. But one thing is certain: the days of easy profits for foreign baby formula companies are over.