Two Hong Kong millennials decided 2015 was a great time to open a North Korea travel company

Hong Kong

Hong Kong

In 2015, Pyongyang announced it had resumed operations at its main nuclear reactor, renewing fears around the world about its weapons program. That year it also carried out a slew of executions. Also that year, Hong Kong locals Rubio Chan and Jamie Cheung decided to start a travel business focusing on North Korea.

The two 27-year-olds, who met when they were in high school, started Hong Kong-based GLO Travel—”GLO” stands for “go local”—to help people understand a country that they say is far more complex than conveyed by the coverage of its missile tests and nuclear program, or the quirky photographs of leader Kim Jong-un.

At the best of times, running a travel agency focused on a country ruled by a dictatorial regime with nuclear ambitions is laden with ethical dilemmas. Critics of engagement say that the regime in capital Pyongyang tightly controls what visitors see and that at least some funds spent by travelers likely go to its military program. Things have only gotten more sensitive since GLO started, as tensions between North Korea and the US have ratcheted up. Last month, a young American student died after returning to the US from his detention in North Korea—he had been held for over a year (paywall) in the country after traveling there with a travel operator based in mainland China.

But Cheung and Chan plan to keep offering tours—the next one begins this week—though they are no longer taking US citizens. GLO says the earnings generated by its trips are insignificant in terms of North Korea’s roughly $4 billion in annual military spending (about a quarter of the food-scarce country’s GDP).

“We are also staunch believers in engagement, and that through exchange and interactions with North Koreans… it would impact Korean individuals and supplement their often polarized worldview,” says Chan.

Travel bugs

The two first hatched a plan of opening a travel agency while at university.

“We both studied politics and international relations-related courses. It made us eager to know the stories behind each spot or attraction whenever we travel,” says Cheung. “If there is no proper preparation, your experience and association with a place will be very limited, even if you are backpacking.”

As undergraduates, they began to organize student tours to nearby Macau, a former Portuguese colony, then to North Korea. It’s not as unlikely a leap as it sounds—a number of agencies in Hong Kong and mainland China organize travel to the country. Among them is Beijing-based Koryo Tours, which was founded by a British expat in 1993 and takes many Western travelers (it processes “thousands” of visa applications in a year, it says). In Hong Kong, local travel agencies such as Wing On, Anytour, and Jetour also arrange North Korea travel.

The two started a travel agency in 2014 that takes students to a range of challenging destinations. The following year they started GLO. The agency, which operates out of a small office in Hong Kong’s Kowloon area, focuses on taking Asian travelers to North Korea, and on fostering interactions between visitors and locals.

The North Korea itineraries come about through discussion with contacts the founders met on their earlier trips. Chan, for example, says he met officials in North Korea during his first trip to the country in 2012 with a Canadian nonprofit. In this way, they’ve arranged visits to high schools, department stores, a kindergarten for deaf children, and farms in Sariwon, a city about 40 miles (64 km) outside Pyongyang. While the visits mostly focus Pyongyang, the country’s most affluent city and home to its elites, GLO also takes travelers beyond the capital.

“The itinerary result is about give-and-take,” Cheung says.

Usually, Cheung and Chan inform North Korean officials of the places they want to visit and who’ll be going, limiting groups to 22 people or fewer. The officials then consider the extent of access they’ll give, which is also shaped by what the two will bring to North Korea. For example, they’ve provided stationery to a secondary school and installed educational software—Mandarin, English, and sometimes science—on its computers.

The price of trips ranges from HK$8,000 to HK$14,000 (about $1,000 to $1,800) for about a week. Travel usually involves arriving by plane and returning by train to China.

Earlier North Korea had tried to promote tourism projects with South Korea, but that came crashing to a halt with the 2008 shooting of a tourist and Kim Jong-un’s ascension to power after his father’s death in 2011. It has since focused on China (pdf). Estimates are uncertain, but a South Korean think tank, Korea Maritime Institute, put earnings in 2014 at $30 million to $44 million. Yoon In Joo, senior researcher at the think-tank, said via e-mail that her rough estimate would put 2016 earnings at somewhere between $44 million and $63 million. All travelers to North Korea require visas, except Chinese travelers going for a day or two to one region, or diplomatic passport holders of a few countries.

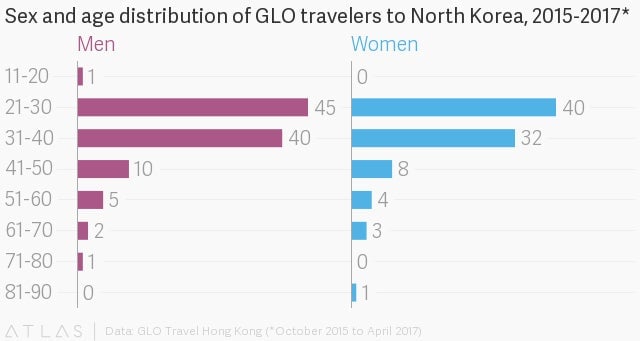

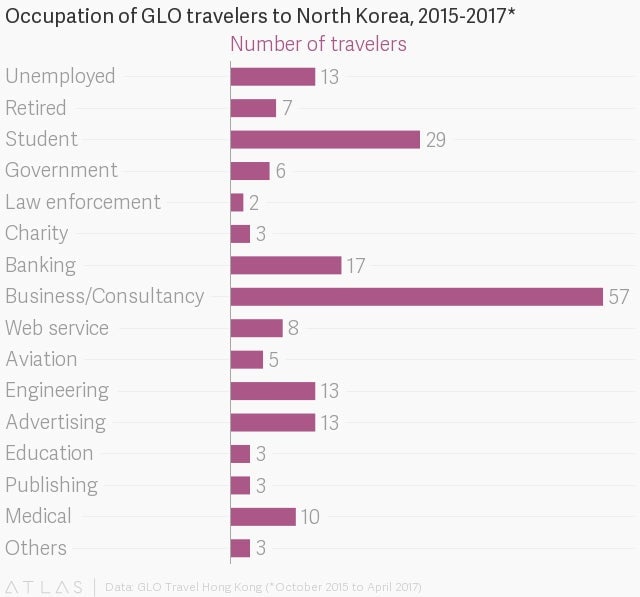

Between October 2015 and April 2017, GLO took nearly 200 travelers to North Korea, most of them in their 20s, and nearly as many women as men. The bulk of them—about 90%—are from Hong Kong, and the rest from Taiwan, Macau, China, Japan, the UK, and Germany.

Attitude adjustment

Many GLO customers approach the agency only after doing their own thorough research on North Korea. But the founders say they nevertheless provide a pre-trip briefing and information pack to participants, to make sure they have a clear picture of the rules to follow.

“We never promote our tours as having fun or being adventurous in North Korea; instead, we encourage our travelers to be observant and open-minded, hoping that the tour would be an insightful one,” GLO wrote in an email.

Cheung says GLO travelers might have unscripted encounters with North Koreans during “free street-roaming time” or while shopping at the state-run Pyongyang Gwangbok department store, which sells furniture, groceries, and local snacks.

“They are actually friendly and will not avoid you if you approach,” Cheung says. “But you will have to understand, they have certain answers for certain questions—for example, how they feel about North Korean defectors. They will tell you those people are traitors, that’s it,” he added. That is, if you have enough Korean to converse—though English can sometimes work, too.

Chan says his travels (link in Chinese) showed him points of common ground—talking about their own daily lives, love lives, and children’s futures. Many children there have seen the Disney movie The Lion King, while adults have watched the South Korean TV drama Winter Sonata and the British movie Bend It Like Beckham, which aired on North Korean TV in 2010, heavily edited.

Cheung and Chan say that while they haven’t seen major changes over the years, tourists are gradually being allowed to visit more cities and sites than before. A trip set for August will take in the cities of Hoeryong, Namyang, Chongjin, and Rason in the northeastern part of the country.

“We are able to arrange more special itineraries like visiting Kenji Fujimoto’s sushi shop and even a home visit to a local family in Lunar New Year,” says Cheung, referring to the Japanese man who was personal chef to former leader Kim Jong-il.

What travelers remember about North Korea

Stephen Fung, a Hong Konger, traveled with GLO to Pyongyang in January 2016 in a group of 10. He wanted to explore the secluded country as a photographer, and says as a result of the trip he became more strongly aware that North Korea is a place where serious human right problems take place.

He remembers the cleanliness of the Pyongyang Metro with its green-and-red trains—but also how soldiers and airport authorities reproached him for taking photos of them.

This week, the agency is taking travelers on a $1,400 visit from July 22-28 (link in Chinese), during which time North Korea will celebrate the end of Korean War hostilities on July 27, 1953, a date known in the country as “Victory Day.” It’s a popular time for North Korea tours, as it’s marked with a military parade and a fireworks display. Japanese citizens aren’t allowed on this trip.

While some stops seem similar to those planned by other agencies—a visit to the Tower of Juche Idea and a ride on the subway system—the itinerary also includes a visit to a middle school, a church, and an educational center to meet with adults who speak Chinese and English.

“The North Korea that news articles mention doesn’t look like the North Korea we have been to,” says Cheung. “It’s hard to imagine what North Korea is like without going there.”