How a brash New York City comptroller could streamroll Wall Street

The news that Eliot Spitzer, the former New York state governor brought low by a prostitution scandal, will run for the office of New York City comptroller—essentially, municipal fiscal watchdog—was mostly greeted by titillation. If the city might wind up with a mayor known for tweeting lewd photos, why not a comptroller known as “client no. 9”?

The news that Eliot Spitzer, the former New York state governor brought low by a prostitution scandal, will run for the office of New York City comptroller—essentially, municipal fiscal watchdog—was mostly greeted by titillation. If the city might wind up with a mayor known for tweeting lewd photos, why not a comptroller known as “client no. 9”?

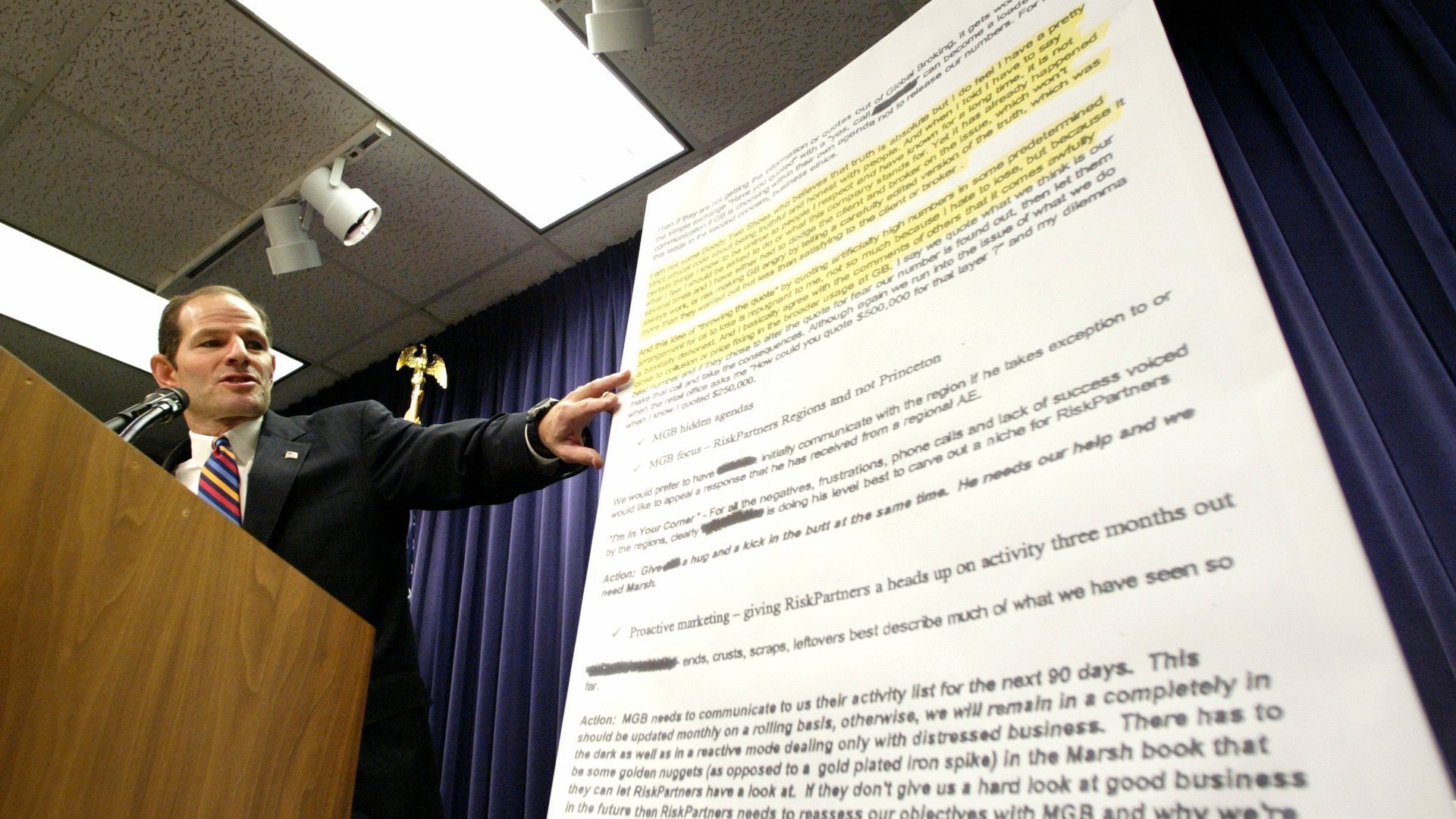

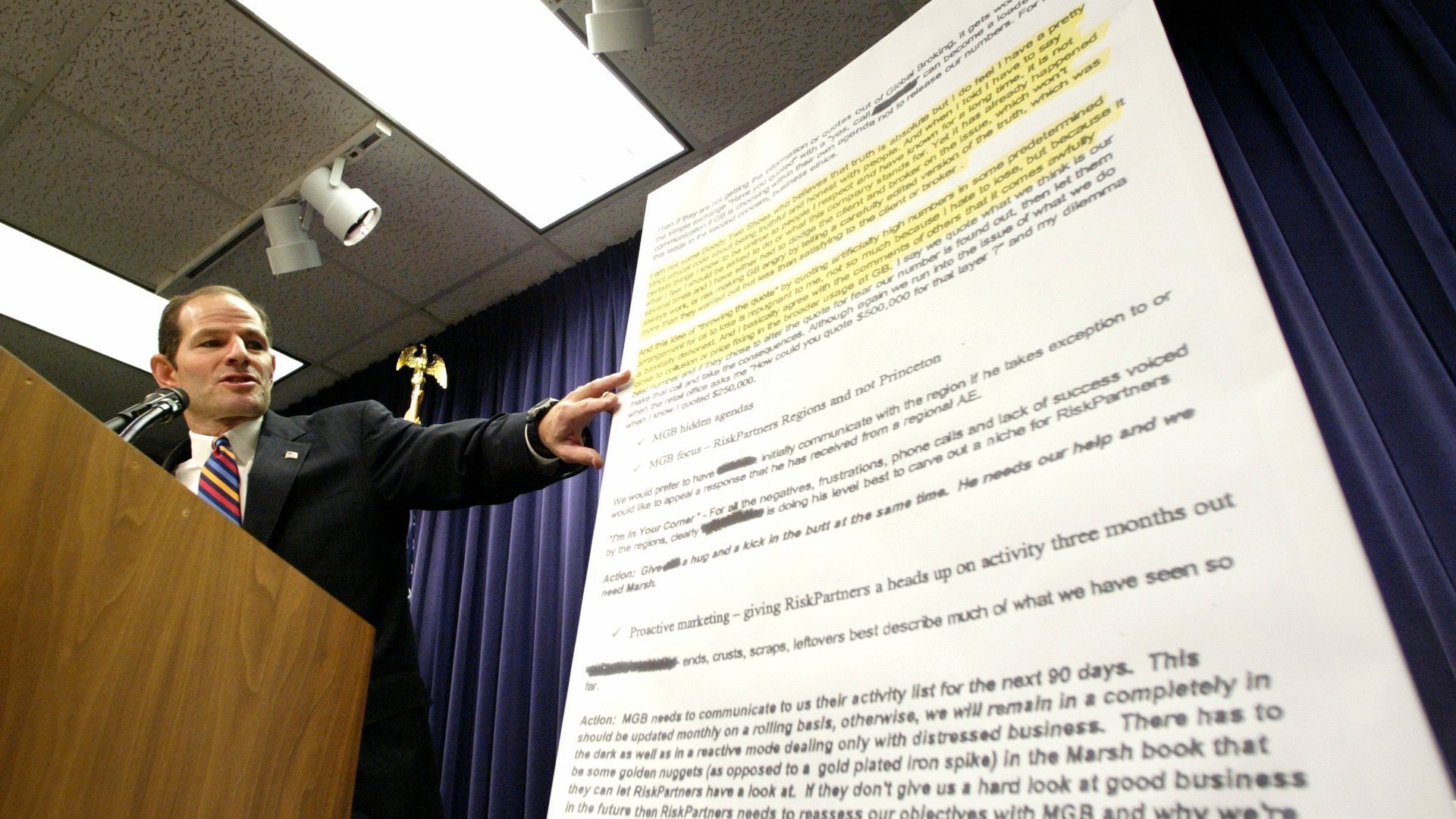

While Spitzer faces tough competition for the job from Scott Stringer, the New York politician seen as the front-runner, the ultimate winner could learn a lot from Spitzer’s time as the state’s attorney general, when he angered banks with an innovative and aggressive regulatory strategy. That seems to be Spitzer’s platform; as he told the New York Times, the office of comptroller “is ripe for greater and more exciting use of the office’s jurisdiction.” While some may hope that Spitzer will stick to cutting pensions and going after unions on behalf of city taxpayers, it’s clear he’s itching to go after Wall Street again, using the comptroller’s powers as the trustee of the $140 billion in the city’s five pension funds.

Spitzer essentially wrote the blueprint for this one after the financial crisis hit pensions and investors of all sorts. He thinks comptrollers should band together the way state attorneys general do and force Wall Street banks to disclose more about their practices, and, more worryingly for the banks, stop spending shareholder money to influence politicians. A group of dedicated funds owning a significant share in major banks would have both the voting rights and standing to sue, and thus be able to force these issues.

Shareholder efforts like these are often dreamt about by reformers, but they don’t usually don’t get very far. However, few people expected Spitzer to earn a $1.4 billion settlement from banks for inflating tech stock prices and giving biased advice, either.

There’s also “say on pay,” the Dodd-Frank provision giving shareholders a vote on executive compensation. It is seen as toothless, mostly creating a cottage industry for lawyers to garner six-figure settlements in exchange for minor disclosures. A more a tenacious legal approach might, however, embarrass companies and get more results for shareholders.

Beyond corporate governance, Spitzer could push measures to change the way companies deal with environmental issues, labor abuses in their supply chains, and even non-discrimination policies. But cases like this will have less of a bearing on the city pension funds’ returns, so they will be seen as doing more to build Spitzer’s future political ambitions than help the city.

The end result of Spitzer’s election will be to turn the New York City pension funds into the world’s angriest activist investor. Right now the comptroller, as the funds’ representative, votes with management of the companies they invest in 76% of the time (pdf, p.1). Do you think the politician who described himself as a “fucking steamroller” and casually threatened a former Goldman Sachs chairman will spend that much time siding with big companies?