Trump has awakened an American “craftivism” movement that’s been dormant since the 1980s AIDS quilt

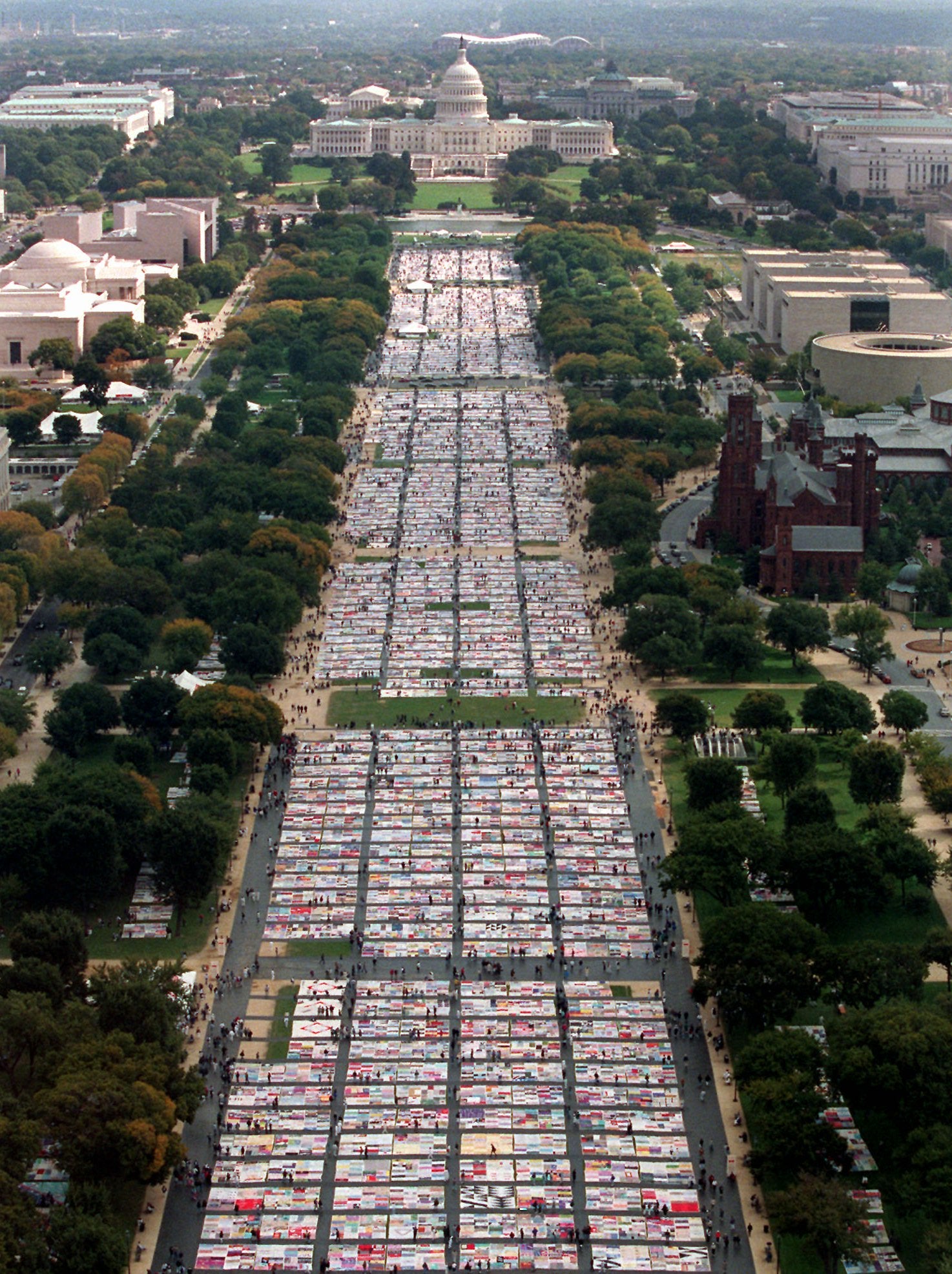

Thirty years ago, an enormous crowd-sourced quilt was first unfurled on the National Mall in Washington, DC. Comprised of thousands of lovingly hand-sewn panels commemorating lives lost in the AIDS epidemic, the massive Memorial Quilt was an indelible example of hobby craft deployed for political protest, called “craftivism.”

Thirty years ago, an enormous crowd-sourced quilt was first unfurled on the National Mall in Washington, DC. Comprised of thousands of lovingly hand-sewn panels commemorating lives lost in the AIDS epidemic, the massive Memorial Quilt was an indelible example of hobby craft deployed for political protest, called “craftivism.”

The quilt’s homespun aesthetic is making a comeback, said artist Marlene McCarty at Cooper Union’s Typographics design festival last month. Once “associated with the language of the oppressed, repressed, and the unrepresented,” hobby crafts such as needle-point, crochet, knitting, lettering, and quilting are giving voice to DIY makers of all stripes.

“Who knew that from that rich era of activism that the piece that would translate into 21st-century activism was the AIDS Quilt?” said McCarty, a member of the legendary AIDS activist collective Gran Fury. “The AIDS Quilt, during its time, was quietly reviled by AIDS activists for taking the soft line—being too sentimental, too mushy.”

During the branding-obsessed 1980s and 90s, the ideal protest sign looked very professional—using clear typography for optimal legibility, McCarty explained. “The idea was to make your work look super strong—the more activist work could immediate immensely influential advertising… the more people would look at it or the more people would take it earnestly.”

The taste for slick, mass-printed messaging has since waned. In lieu of ready-made, professionally-designed protest paraphernalia, today’s activists—armed with glue guns, sewing needles, and X-ACTO craft knives—are making one-of-a-kind protest gear. An eclectic sampler can be often be spotted in the various rallies and marches protesting president Donald Trump’s controversial policies.

Today, legions of subversive embroiderers, yarn bombers, rage knitters, and crusader calligraphers deliver punchy messages through traditional arts and crafts. There is a thriving “craftivism” practice on Etsy.

Among the most visible anti-Trump craftivist actions is the Pussyhat Project that debuted during the Women’s March in January. Spurred by Trump’s leaked “locker room talk,” thousands channeled their outrage into knitting pink beanies with pussy cat-like ears to “reclaim the term as a means of empowerment,” as founders Krista Suh and Jayna Zweiman explained.

Beyond the sea of pink-capped protesters who made it to Washington, thousands more participated by knitting caps for others.

Craftivism in the US is largely associated with the resurgent feminist movement, but its roots trace back to colonial times. In the 1760s, women revolted against British taxation on textiles by spinning their own yarn and sewing their family’s clothes. Famous spy Molly “Old Mom” Rinker smuggled messages to George Washington’s troops through balls of yarn.

Craftivism is all about intentional, individual action, explains Sarah Corbett, author of the forthcoming book, How to be a Craftivist: the Art of Gentle Protest. “The speed and ease of signing an online petition or tweeting our protests is making power holders doubt the commitment of protesters,” she says, calling craftivism an antidote to social media-enabled “slacktivism.”

As the title of her book suggests, Corbett advocates for a “gentler” rebellion. Craftmaking, she explains, is an avenue for less vociferous activists or those tired of angry polemics.

“I work with lots of people put off by traditional activism or extrovert activism because they are introverts,” she explains. Corbet, who founded Craftivist Collective in the UK eight years ago, describes the labor-intensive activity as “slow activism.” Craftivism “forces the maker to slow down and think slowly and strategically… using the comfort of craft to meditate on big, complex injustice issues with many different answers.”

“The Trump administration has basically given us a trope of what happens when we get too disconnected from ourselves, our realities and people who are different than us,” adds Betsy Greer, the so-called “godmother of craftivism,” Crafting, she explains, can foster non-threatening dialogue across party lines. “It helps change up the narrative some people tend to have that protest is [always] aggressive, which, while valuable, tends to shut down conversations.”