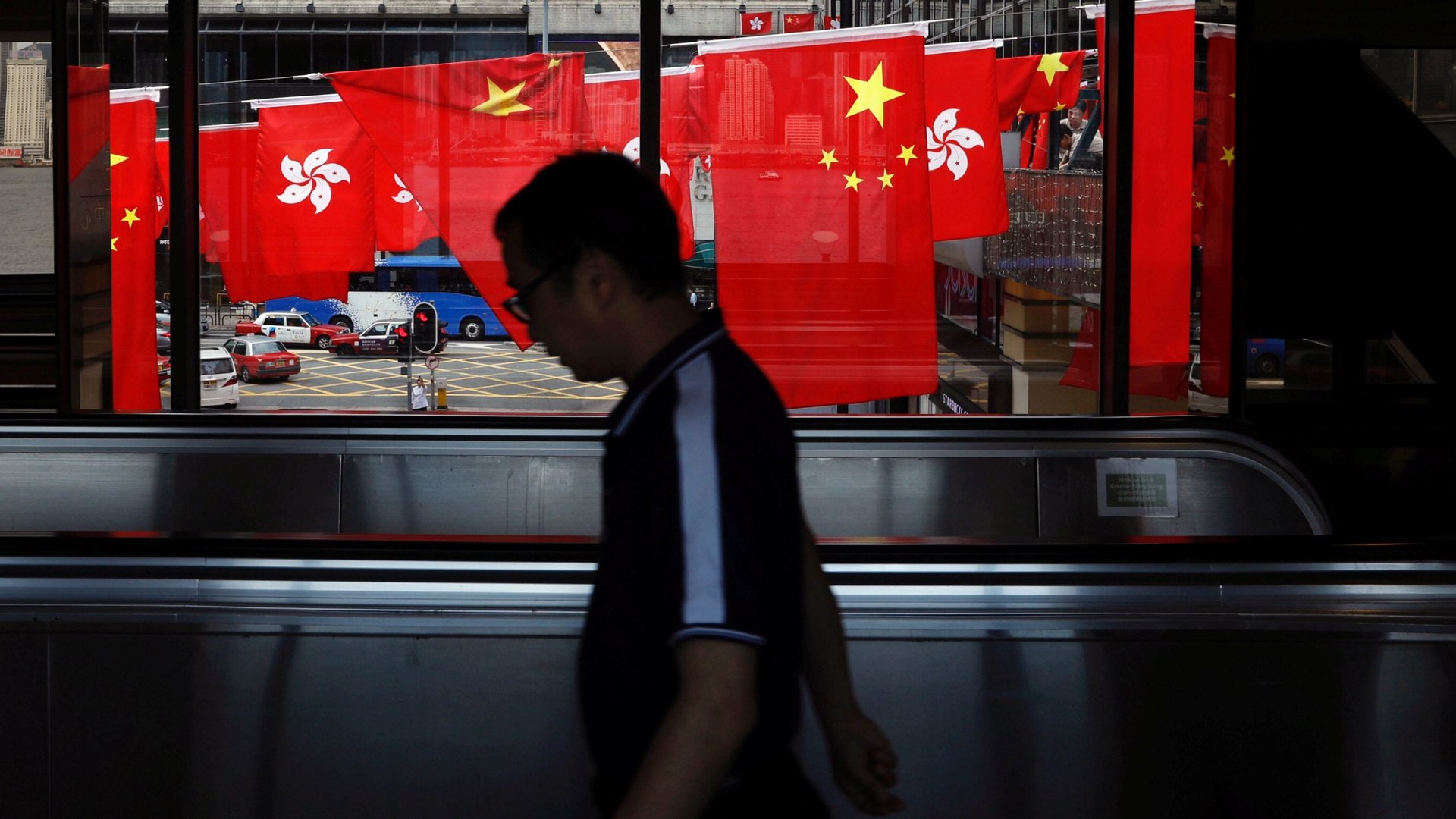

“If you are born and raised in Hong Kong, you care about Hong Kong’s future more than anything”

This extract has been excerpted with permission from PEN Hong Kong from the essay “Hometown,” by Kris Cheng, part of the anthology Hong Kong 20/20: Reflections on a Borrowed Place, out this month from Blacksmith Books.

This extract has been excerpted with permission from PEN Hong Kong from the essay “Hometown,” by Kris Cheng, part of the anthology Hong Kong 20/20: Reflections on a Borrowed Place, out this month from Blacksmith Books.

Each spring, I face the same question about my travel plans.

‘So are you going to baai saan this year? It’s almost time you visited again,’ my father says. Baai saan, or ‘visit the mountain’, means to visit Zhongshan city in Guandong province. More specifically—and importantly for my father—it means visiting the graves of my ancestors…

The trips for me consist mostly of watching older family members perform rituals on the hill to pay respect to my grandparents at the ancestral home—they trim the wild grass, place fruit and other gifts on the graves, fold paper money as an offering… it is mostly because of my grandfather that I was born and raised in Hong Kong.

My grandfather, whom I never met, was a member of the ousted Kuomintang and a train station manager, according to my father. My grandfather did not like the Communist Party. One day, he badmouthed it and was later convicted as a counter-revolutionary and sent to a labour camp in the northeast province of Heilongjiang for ten years. He survived but lived in fear after returning home to Zhongshan. He died a few years later.

My father left China to come to Hong Kong in the 1980s because there was not much opportunity for him on the mainland. He was a teacher, but because of his family background he could never join the party, and therefore would not have been able to rise very far in his career. My father ran a label printing company in Hong Kong to feed the family and never really cared about politics. ‘Those who suit their actions to the time are wise,’ he often said, quoting a Chinese adage. He thought the young people in Hong Kong who joined mass protests against the express rail link and other wasteful publicly-funded infrastructure projects, or against the government in general, were a weird bunch. ‘Why care about politics so much?’ he would ask. ‘Why provoke the government and end up like your grandfather?’

But to me, the answer comes naturally: if you are born and raised in Hong Kong, you care about Hong Kong’s future more than anything.

I was a good student and passed the first secondary school public exam in secondary five with flying colours, so I was allowed to skip the second public exam in secondary seven. Because I was basically free from studies, I think I was open to a political enlightenment. This relative freedom came for me during 2006 and 2007, during the protests against the demolition of the former Star Ferry Pier. Those who favoured demolition argued that the structure was a symbol of colonialism. Like so many other young people, I had no vivid memories of the colonial days. To us, the structure had come to represent Hong Kong itself, and did not need to represent the past…

The movement to save the old Star Ferry Pier was often compared to the 1966 riots sparked by the fare rise of the Star Ferry (supported by the colonial government) that triggered the hunger strike of a twenty-seven-year-old man, So Sau-chung. Crowds of people supported So and his cause and riots erupted after he was arrested and sentenced to jail.

Only after the protests of 2006 and 2007 did my father tell me Mr. So was a relative of ours. He mentioned it after seeing an article about So in the newspaper, and he even asked me whether I could find a contact number for So (I did, but my father never called him). Apparently, So left his family and became a monk. Perhaps So’s ordeal was another reason why my father did not encourage people to protest. But although I never met So, and he was only a distant cousin, I felt a historical connection to him and felt less alone.

In 2008, Hong Kong became a centre of debate over the Beijing Olympics (the equestrian event took place here). The Olympic torch passed through Hong Kong in May that year. As a first-year university student, I joined a group that planned to carry banners during the torch run through Sha Tin in the New Territories to protest the mainland government’s propaganda, which seemed to exclude any room for criticism or even questioning what it meant to be Chinese…

In fact, my father is becoming more active in current affairs himself, even if quietly and indirectly. A few years ago, my father joined an association of people from Zhongshan. He explained to me he wanted to help his hometown, particularly the people there who helped him during the years of turmoil in China. He is an active member, often joining the trips back to Zhongshan to do volunteer work, or attending gala dinners to raise funds to improve the city. To show him the support he has shown me, I often tell him I respect his choice. But I also tell him he should be careful of political involvement through the association, which often encourages members who live in Hong Kong to support pro-Beijing causes. At the request of his association, sometimes my father even turns up at some pro-government events. He maintains he is simply being pragmatic.

Sometimes I show him news reports of some pro-government protesters who were paid to show up, and jokingly tell him it was a bit foolish of him to pay bus fare out of his own pocket to attend. ‘I don’t like the Communist Party, more than anyone, but I am not opposing everything for the sake of opposing,’ he answers. ‘I support whatever is good for Hong Kong and my hometown.’

I may not fully relate to my father’s emotional attachment to his hometown, but at the same time he may not completely grasp the concerns I have about mine, as we grew up so very differently. But I am thankful that we can talk about our disagreements honestly—at least I can understand how he came to hold his views, and maybe with time he will understand how I came to hold mine.

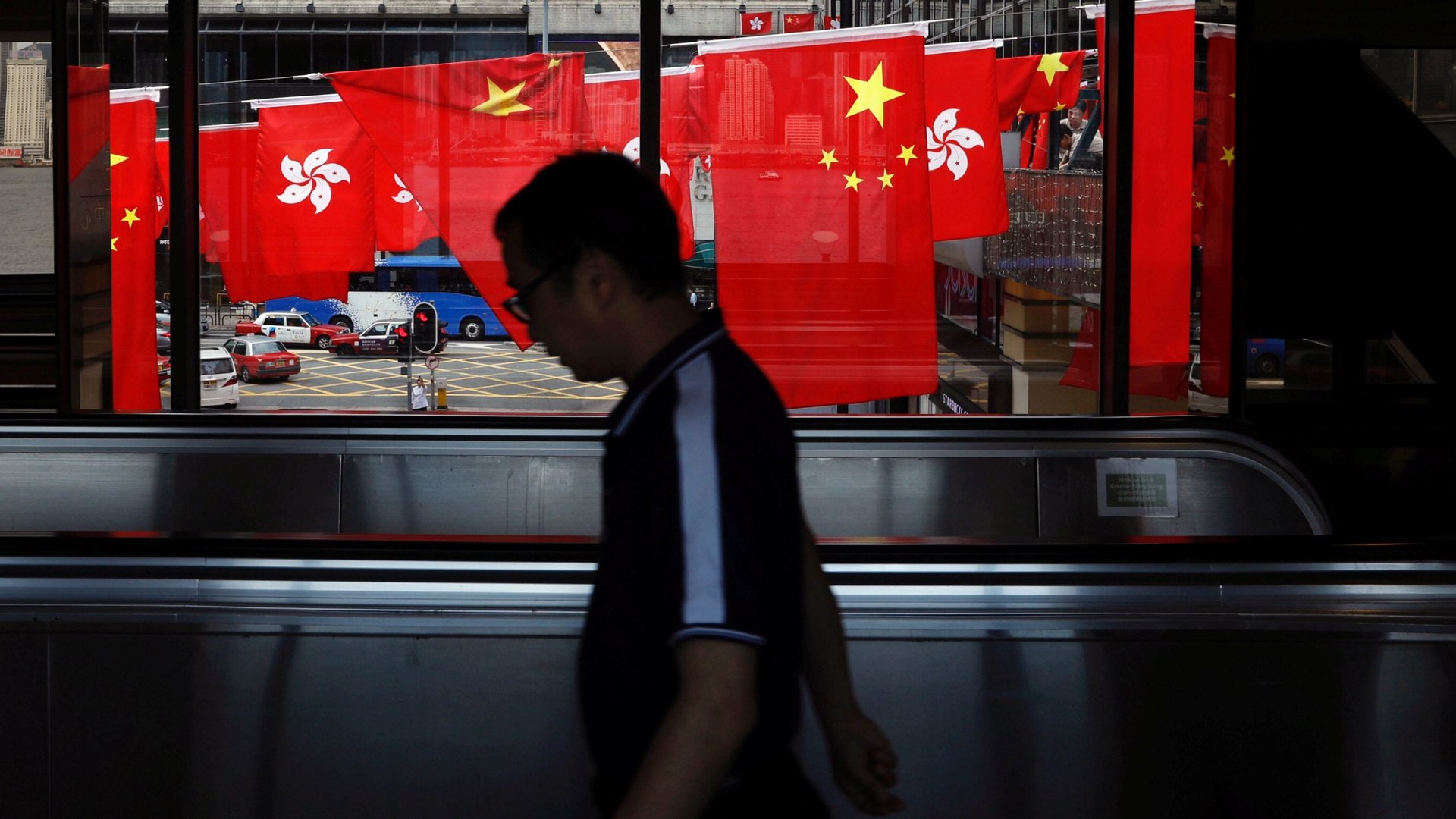

Read Quartz’s complete series on the 20th anniversary of the Hong Kong handover.