The chills we get from listening to music are a biological reaction to surprise

Think of your favorite song of all time. Play it, even. Take a moment to get lost in the rhythm, the melody, the lyrics, and whatever they make you feel.

Think of your favorite song of all time. Play it, even. Take a moment to get lost in the rhythm, the melody, the lyrics, and whatever they make you feel.

Good to go? Great.

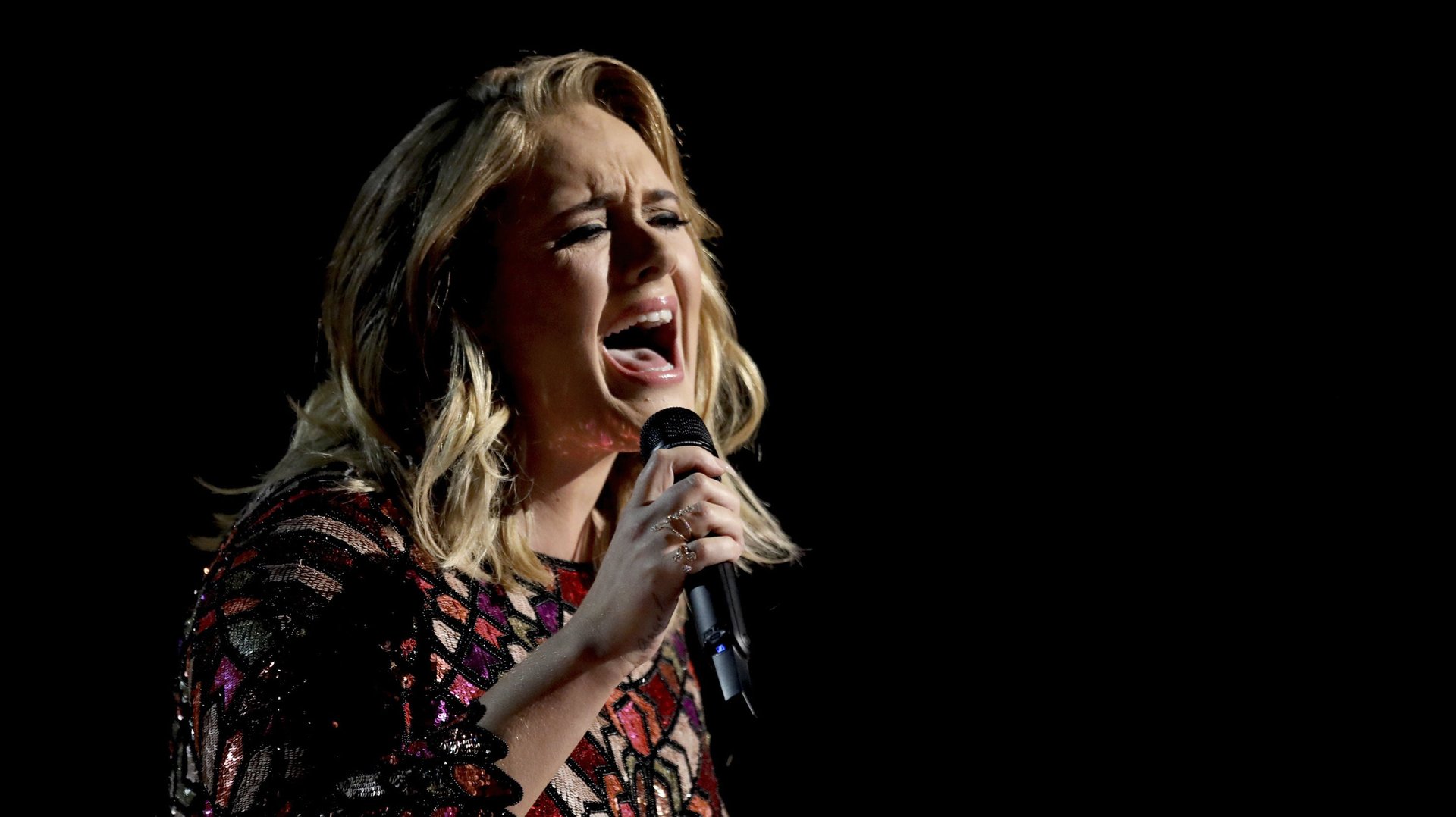

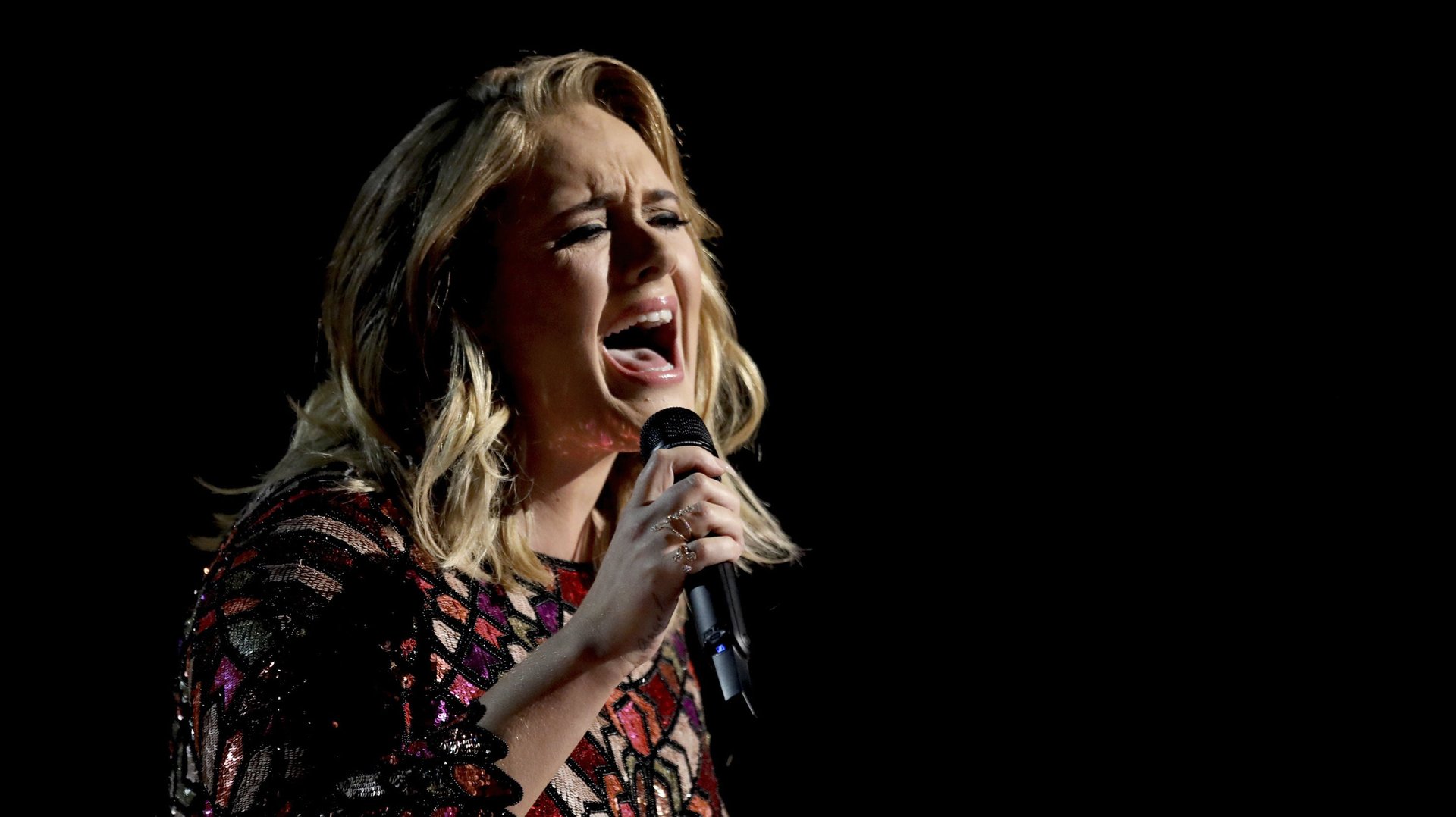

There’s no telling what you picked. There might have been some hauntingly high notes peppered in there. It was probably something you listened to during an emotionally charged time in your life. And if you’re lucky, it also gave you a slight chill.

By one estimate (paywall), about half of us feel a tingling when we hear certain songs. It’s a sensation sometimes referred to as a “skin orgasm,” but known as “frisson” in the scientific community. Songs can also bring a lump to the back of our throat, send our heart rate up, and make our skin clammy. All interesting physical responses to something we’re arguably doing for pleasure.

“Chills are generally a response to feeling cold,” says Matthew Sachs, a graduate student studying the effect of music on the brain at the University of Southern California. “Our hair stands on end, and when we’re threatened, it makes us look larger.”

Sachs (who also plays the bassoon and piano), has been examining physical reactions to music since he was an undergraduate at Harvard University. Last year, he and his team published the results of a study involving 20 students, 10 of whom reported feeling chills while listening to their favorite songs and 10 of whom did not. Researchers took brain scans of both groups. They found that the group who experienced chills had a significantly higher number of neural connections between their auditory cortex; emotional processing centers; and prefrontal cortex, which is involved in higher-order cognition (like interpreting a song’s meaning).

Admittedly, it was a very small study, and Sachs concedes that this is a difficult phenomenon to research. Often, people who get chills from certain songs have unique memories tied to them, and those are impossible to control for in a laboratory setting. Sachs is currently conducting follow-up research that includes examining the patterns of activity in people’s brains while they listen to goosebumps-inducing music; he’s hoping to understand more about what, neurologically speaking, causes that reaction.

It is safe to assume, though, that everything our bodies do is loosely based in evolution. We’re primed to hear certain sounds, like high notes or falsettos, because they represent crying or wailing, the universal human distress signal. But music is a safe space. Once our brains recognize it, even surprises—like jumps along a scale or dramatic crescendos—can be pleasurable.

“We do seem to like having these challenges,” Jessica Grahn, a neuroscientist studying music in neuroscience at Western University in Canada, told the Guardian. She says it’s similar to the way people seek out haunted houses or scary movies for fun. Indeed, other research (paywall), out of Eastern Washington University, has shown that people who are more open to unpredictable experiences are often more likely to experience visceral reactions to music or other kinds of art.

Take this version of “What I’m Doing Here,” a song by Lake Street Dive, sung by Rachael Price.

This blues piece was written by Price herself, who is a trained jazz singer. Right around 2:06, she sings at comparatively lower notes, followed by a crescendo where she hits an extremely high note before dropping back down immediately afterward. The quick turnaround between the high and low notes, combined with the build-up in between, is climactic, surprising, and resembles wailing in a way. And if all that weren’t enough, there’s a key change a few seconds later (around 2:50) that offers another unexpected treat for the ears.

It’s more than enough to give me chills, and sometimes a lump in the back of my throat. That said, this song resonated with me during an emotionally charged time in my life; those memories undoubtedly enhance my listening experience.

In part because of these reactions, Sachs thinks music has untapped therapeutic potential. Currently, music therapy is used for relaxation, and making music as a group can sometimes yield team-building side effects. As Grahn notes in the Guardian, emotion regulation is already “one of the most common reasons people put music on and decide to listen to it.”

But Sachs thinks music could do even more, starting with playing a role in treatment for depressive disorders. “Depression causes an inability to experience pleasure of everyday things,” he says. “You could use music with a therapist to explore feelings.” He hopes to conduct research involving music and patients with manic-depressive disorder in the future.