How the world’s most important financial benchmark makes money

The British Bankers’ Association (BBA) voted unanimously to sell Libor—the London Interbank Offered Rate—to NYSE Euronext, the US-based stock exchange company. Libor, calculated based on rates at which the world’s largest financial institutions say they can lend to each other on a daily basis, is the world’s most important financial benchmark; it’s what helps determine interest rates on everything from home loans and credit cards to complex derivatives transactions. Both companies expect to complete the transition by early 2014.

The British Bankers’ Association (BBA) voted unanimously to sell Libor—the London Interbank Offered Rate—to NYSE Euronext, the US-based stock exchange company. Libor, calculated based on rates at which the world’s largest financial institutions say they can lend to each other on a daily basis, is the world’s most important financial benchmark; it’s what helps determine interest rates on everything from home loans and credit cards to complex derivatives transactions. Both companies expect to complete the transition by early 2014.

The sale price was meager. NYSE Euronext bought the rate from BBA for a reported $1.49. But managing the world’s most important rate is a moneymaker.

Here’s how the moneymaking comes about: Each day, bankers at a select number of banks submit a rate they say their bank can borrow at in a certain currency to a distributor. That distributor is currently Thomson Reuters, which then throws out the highest and lowest submissions and averages the remaining ones to calculate the day’s Libor rate in that currency. Thomson Reuters then publishes both the final rate and the rates each bank submitted.

The BBA’s stewardship of Libor has been tainted by scandal; for much of the 2000s, US and UK regulators have found, bankers were able to manipulate the rate, either to boost their own performance or make their firm seem more financially stable than it was. UK regulators led by the Financial Service Authority’s Martin Wheatley recommended that the BBA pass on the administration of the rate to another body in its September 2012 report (pdf). UK regulators invited financial firms to submit bids for the rate in April, and ultimately settled on NYSE Euronext. The sale was orchestrated by the UK government, but the process includes a transfer of assets between the two organizations.

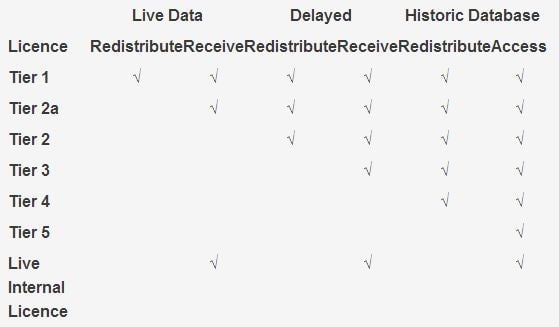

Institutions that want Libor data currently pay for it on a tiered pricing scheme. Tier 1 access provides subscribers with a real-time data feed of all the rates at 11:30am that they can turn around and publish. Other tiers permit a variety of forms of real-time or delayed access, but they limit when subscribers can give that data out to clients or others. A live internal license gives users live data without any redistribution power.

That system isn’t likely to change much with new ownership, particularly since regulators still wanted a private company to compile Libor. The Wheatley report last fall explained:

The Wheatley Review has concluded that Libor can and should be successfully administered by private organisations, within rules and guidance set by the authorities…The Review understands that the balance of incentives may not be sufficient to encourage a new administrator to take ownership of the benchmark in absence of a financial incentive. As a result, the new administrator should be permitted to explore the commercial viability of Libor.

A spokesman for the BBA said it currently makes about £2 million ($3 million) per year from administering the rate, but it declined to comment on the cost of specific pricing contracts, or the terms of the BBA’s current contract with Thomson Reuters.

“We’re a commercial entity and though our primary motivation here is to restore the credibility of Libor, we have a duty to our shareholders,” Stuart Sloan, Executive Director of NYSE Liffe, told Quartz in a phone interview.

Thomson Reuters’ continuing role in the distribution isn’t clear. ”They will continue to [compile data] for the time being, but from then on it’s up to [NYSE Euronext] as to how they’d like to distribute it,” the BBA spokesman said. NYSE Euronext clarified that it had no current contract with Thomson Reuters, but said it works with many data distributors—among them Thomson Reuters and Bloomberg—and has its own data distribution business.

Although the system for calculating the world’s most important benchmark may change, it’s likely Libor will still be a subscription service. ”I think that the benchmark pricing model is reasonably well established,” said Sloan.

Regardless of whether regulators can agree on what they want Libor to be, one thing is clear: the rate will still make someone money.