Exhausted by the herd, single South Koreans are gingerly embracing the “YOLO” lifestyle

Seoul, South Korea

Seoul, South Korea

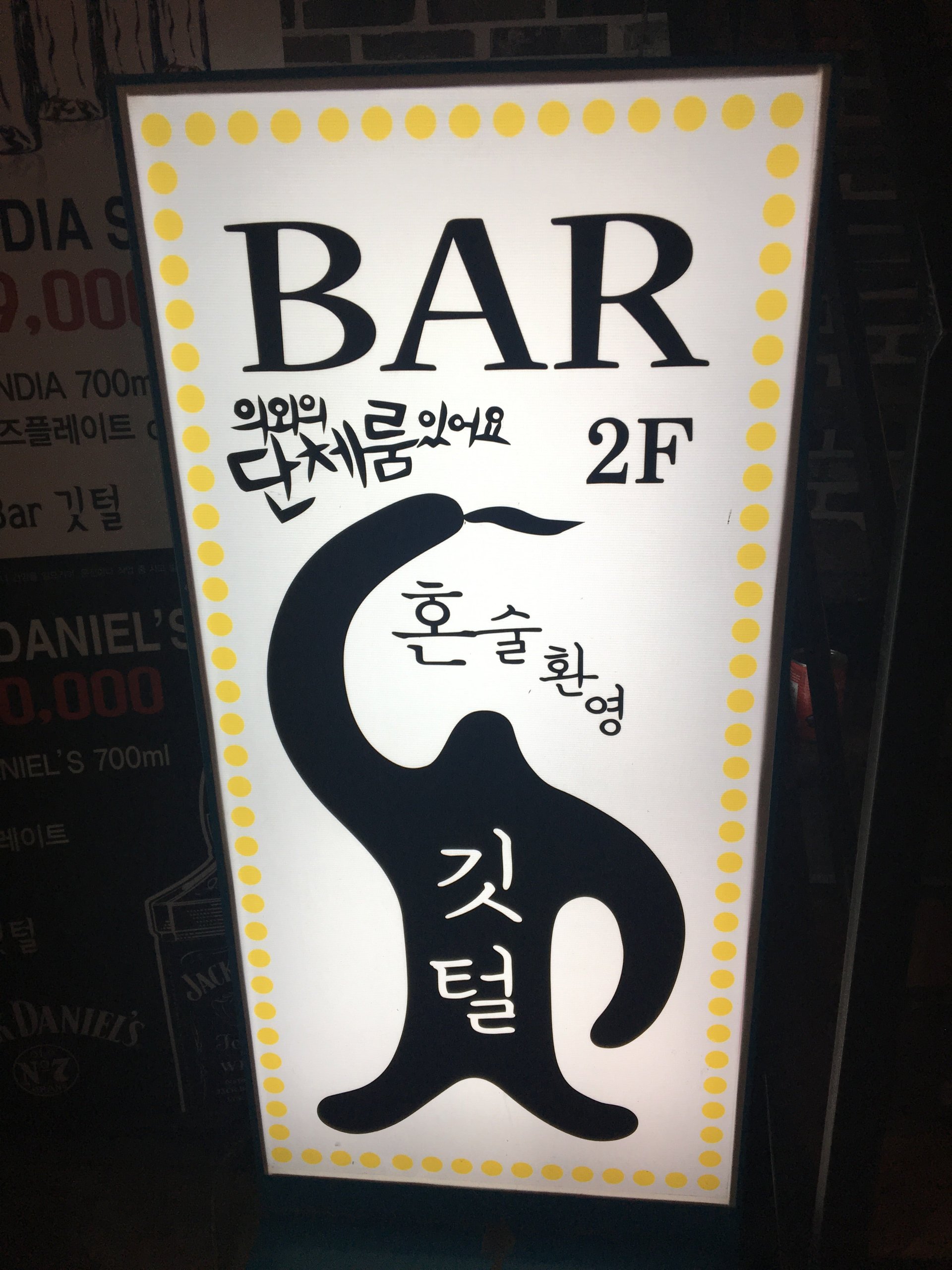

“Drinking alone is welcome here,” reads a sign for a bar in Seoul’s Hongdae district.

Gitteol, whose name means Feather in Korean, opened six months ago after its owner noticed the growing ranks of Koreans engaged in honsul, or drinking alone. On a recent night as she mixed discounted highballs, Hongyang, a 41-year-old painter, said she wanted to give Koreans another choice apart from going out in a group. There’s lots of bar seating, so lone arrivals can chit-chat with her, rather than sticking out uncomfortably at a table by themselves.

South Koreans aren’t only drinking alone. They’re also dining alone, traveling alone, and having weddings alone. That’s a significant shift for a country where the group has long dominated social life, from going out with colleagues after work for dinner and drinks, to hiking en masse (paywall). The change comes as Korean youth experience the same bleak feelings about their futures as people in other countries that face high youth unemployment rates, chronic low pay, and expensive housing. But pressure from families and society at large to succeed is particularly grueling in Korea, and young people are starting to push back against these strict conventions in a serious way—by staying single and seeking more “me” time.

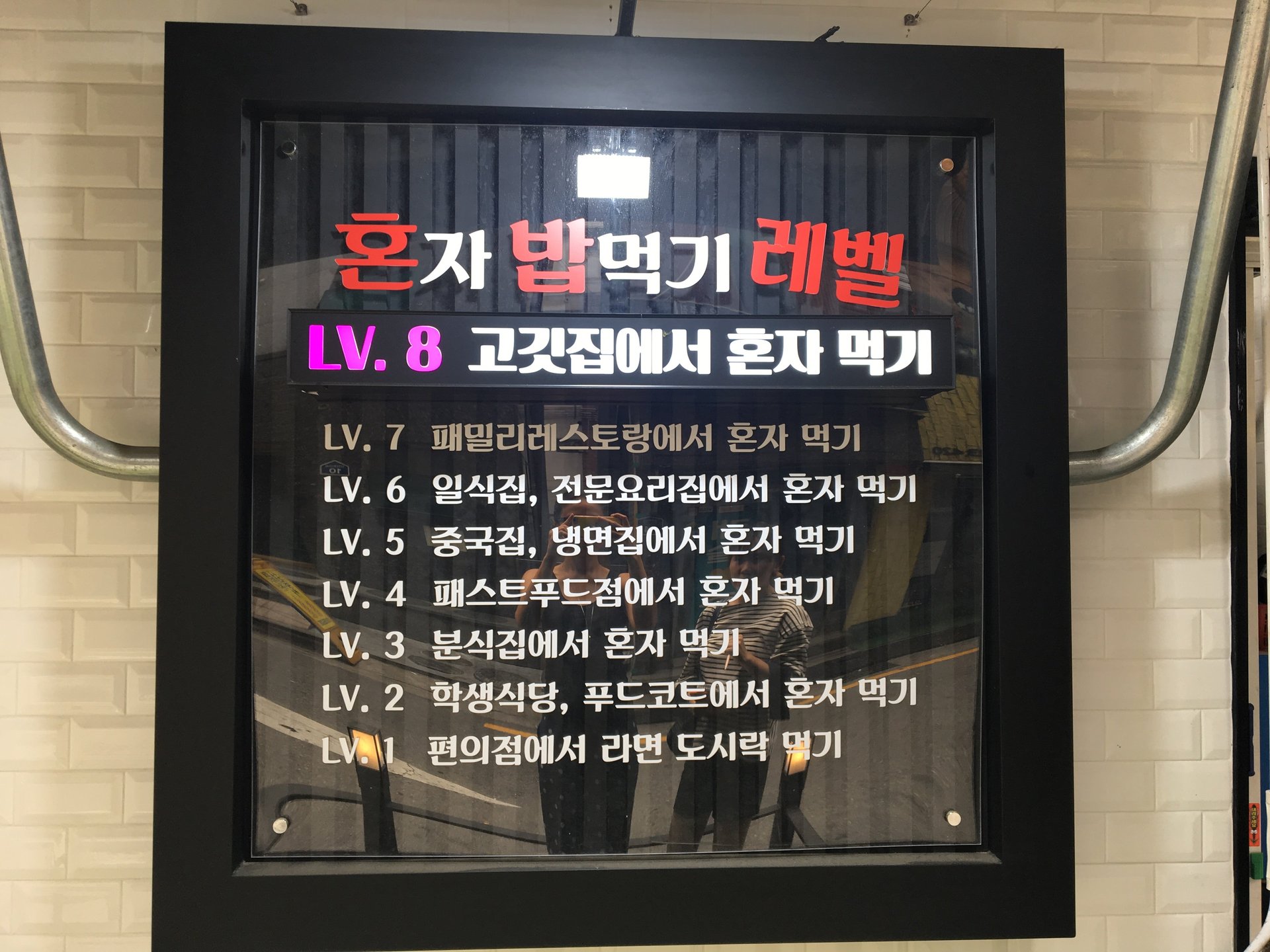

Now, many businesses advertise themselves as friendly to the number of people who self-identify as honjok, or loners. At Yuk Cheop Ban Sang, a barbecue restaurant near the capital’s most prestigious university, a poster shows the eight levels of mastery of honbap, or eating alone. Eating ramen at a convenience store is the lowest level, achievable by anyone, the poster implies, while Korean barbecue, the ultimate group meal, is the most challenging. Inside, solo diners sit on a long bench and cook their meat on single-person-sized grills, facing a partition lined with power outlets for people to charge their phones. In another part of town, a Japanese ramen restaurant allows diners to order through a machine and sit in narrow, partitioned booths where they hardly have to interact.

“In the past, people used to give me looks when I ate alone, but these days I think people don’t think it’s weird,” said Park Da-som, a 25 year-old bank employee who was eating by herself one evening at the ramen restaurant, Ichi-Men. “It’s become a social trend in Korea.”

Solo YOLO

The battle cry for many Koreans for their new-found, individualistic lifestyles is YOLO, or “you only live once”—a term that is widely seen to have been popularized by Canadian rapper Drake in 2011, and which is now endlessly mocked in Western culture. Koreans can now apply for a “YOLO” credit card (link in Korean) from one of the country’s biggest banks, which offers discounts at vendors like Starbucks, cinemas, and convenience stores, sign up for one-day macaron-baking classes or after-work treasure hunts as a gesture of spontaneity, or read a magazine called Singles, which “helps single people to be happy and proud in their choice.”

“YOLO is an abbreviation of ‘you only live once,’ it means that since you only live your life once you should not live for others or for the future, but for the present,” Jeon Mi-young, a research professor at the department of consumer science at Seoul National University said in a November TV (video in Korean) interview. In the past, people focused on saving money and were concerned about what others thought of their consumption habits, Jeon added, but consumption now in Korea is very much about the “emotional and pleasurable rather than rational.”

“A lot of Koreans, until recent years, didn’t know how to resist the social pressures from the collective,” said Katharine Moon, a professor of political science at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. “They’re [now] getting their toes wet a little bit and stepping gingerly into individualism”—which could be as simple as choosing to run an errand during lunch hours instead of eating with colleagues, she added.

Part of the reason for the trend is a simple matter of a scarcity of time and money. Koreans work notoriously long hours, on top of the after-work social obligations employees are expected to fulfill.

“There’s no respect for your own time or values. It’s a really bad part of Korean culture,” said Lee Ju-yeol, a third-year student at Ajou University studying financial engineering. “When you eat alone, it takes up less time and is cheaper than if you do it in a group.” Lee said he was criticized in his previous university, from where he transferred, because he didn’t participate in group meals with other members of the student union. “‘You’ll be eating alone if you behave in this way,’ they told me.”

Koreans doing things by themselves can seem like an anomaly even to outside observers of the society.

“With Westerners, the solitary hiker is not an uncommon sight at all, but with Koreans when you see that, you almost feel that there’s something not right or something odd about them,” said Michael Breen, a long-time resident of Korea and author of the recently published “The New Koreans.”

But data show that sight is going to become a more common one.

All by myself

According to government statistics, single-person households are now the dominant type of household in Korea, making up over 27% of households as of 2015, similar to the level in the US, but a particularly dramatic change for a country where just a decade ago four-person households formed the largest share.

The reasons echo those of other developed countries: more people are moving to cities; many are delaying marriage, and more women are choosing to focus on their careers rather than get pregnant and interrupt their careers—a problem that is particularly acute in Korea. Women make up the majority of single-person households in Korea, according to government statistics, and now less than half of women believe that marriage is a must. According to government data (link in Korean), the number of marriages fell from 329,100 in 2011 to 281,600 in 2016, the lowest level since 1974.

Some women make bold statements about delaying or shunning marriage altogether by having “single weddings.” This could entail having a photo shoot in a wedding dress alone, or hosting an actual wedding ceremony—in part so that they can recoup some of money they’ve spent attending weddings over the years as it is customary in Korea to give cash gifts to newly weds. Lush, the British cosmetics brand, recently celebrated (link in Korean) one of its male employee’s single weddings, giving him cash gifts and wedding leave.

Yang Eun-joo, 32, took wedding photos alone in March after she broke off her engagement last year. Her current boyfriend is divorced, and has no intention of getting married again, and she said she is not thinking about marriage either. “It seems like I won’t be getting married in the future but I wanted to wear a dress… while I’m still young,” said Yang, who works at LG Electronics. “My family still talks to me about marriage, but I don’t have intentions of getting married.”

Choo Beom-seok, the co-owner of Studio Gamsung, a photography studio in Seoul, decided to offer solo wedding photo services earlier this year, and purchased a handful of second-hand wedding dresses and shoes.

Other businesses are rushing to capitalize on single shoppers mostly by shrinking the size of their offerings. Emart, Korea’s largest retailer, said that sales of small (link in Korean), palm-sized “apple watermelons” have been increasing, which they attribute to demand from single people for smaller fruits. White-goods makers are also making smaller home appliances (link in Korean) like rice cookers and washing machines. Business at convenience stores is booming as singles pick up ready-made meals or cups of coffee to consume alone.

“We should consider [single people] as a new consumer class and adopt a more positive view of them,” according to a study of the habits (link in Korean) of single people conducted by KB Financial Group, one of Korea’s biggest financial companies.

Alone, together

The trend toward singledom, however, isn’t exactly being embraced with open arms by the older generation in Korea. Part of the consternation around the rise of single-person households in Korea stems from worries over the country’s ultra-low birthrate—officials say the number of births this year will be a record low. The continuing stigma toward unmarried people having children also means that Korea has the fewest births out of wedlock among OECD countries. The government estimates that Korea’s population will peak in 2031.

Korea’s new president, Moon Jae-in, said in April (link in Korean) that being alone should come with a health warning: “Honbap is not only a lonely thing, but also leads to an unbalanced diet, which harms the health of young people.” He has a different vision for Korean singles, saying he wants the entire country to be “the family of youth who live on their own.” One way, he says, would be to open community kitchens in areas with many one-person households, to turn honbap into hamkkebap, or “eating together.”

Taking another tack, one of Korea’s biggest entertainment congomerates, CJ E&M, wants Koreans to know that they’re not alone in being alone. It’s the producer of a popular Korean television drama airing now that is called “Drinking Solo,” or Honsulnomnyeo. The drama portrays the lives of people from different walks of life who counter their stresses with honsul. Kim Ji-young, a representative from CJ E&M, told Quartz: “As honjok [single people] and single-person households increase, there are more and more programs showing how singles live. People feel comfort and laughter when they see people like themselves on TV.”