What happened on Bastille Day and why is Donald Trump visiting France for it?

In the late 1700s, July was a good month for democracies, and for revolutions. Only 13 years and 10 days after the approval of the American Declaration of Independence, another people began a fight to emancipate itself from monarchy—the French.

In the late 1700s, July was a good month for democracies, and for revolutions. Only 13 years and 10 days after the approval of the American Declaration of Independence, another people began a fight to emancipate itself from monarchy—the French.

The summer of 1789 had started off hot in Paris. The Estates-General, a sort of intermittent parliament composed of three “estates”—clergy, nobility, and commoners—had been convened in May to address a deep economic crisis (made worse by France’s support for the American revolt against Britain), but had ended in gridlock. Fed up, the Third Estate, the commoners, declared itself a National Assembly on June 17. King Louis XVI at first refused to acknowledge its legitimacy, but once the clergy and a few nobles joined it, he gave in. The then-renamed National Constituent Assembly began its legislative work on July 9, effectively replacing the Estates-General.

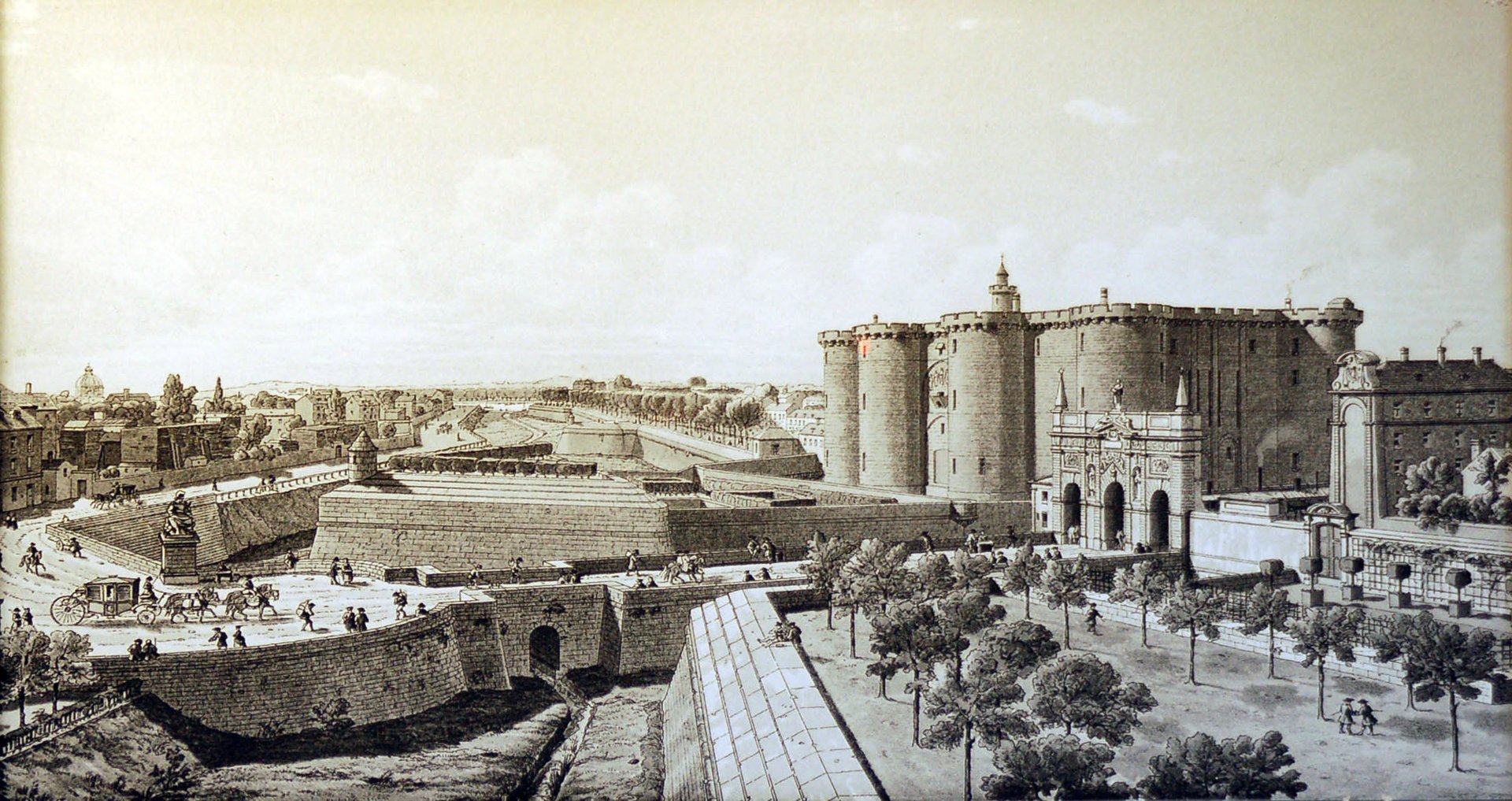

Meanwhile, the streets of Paris were restless—the commoners had formed a militia, and had progressively pushed the city into a state of widespread riot. With the rumor that the king’s army was going to enter the city, the rioters attacked the Hôtel des Invalides, where they believed the army kept a store of weapons. They found weapons but no gunpowder, which had been moved elsewhere: to the Bastille, a medieval fortress employed as a prison. Though by 1789 practically empty (it housed only seven prisoners, none of them held for serious crimes), it remained one of the symbols of royal power in the city, and generated outrage at the costs of keeping it in function.

The vainqueurs de la Bastille (conquerors of the Bastille) were about 1,000—mostly artisans and merchants, members of the bourgeoisie—and they took over the fortress in only a few hours with the help of the French guard, which sided with the rebels. The prise (literally, taking) began at 10:30am on July 14 and finished shortly after 5pm, when the crowd took over the building and removed Bernard-René Jordan de Launa, the Bastille’s governor, who was killed later that day. The following day the demolition of the fortress began.

Legend has it that the king didn’t learn about the storming till the day after, when the Duke of Liancourt, a nobleman who’d become a social reformer and the president of the new constituent assembly, delivered the news of what had happened. “Mais, c’est une révolte?” (“But is it a revolt?”) asked the king. “Non, Sire, c’est une révolution!” replied Liancourt.

He was right: The storming of the Bastille is considered the episode that turned the turmoil in Paris into an actual revolution—which would carry on for a decade under the motto the motto liberté, égalité, fraternité. Though the first French Republic was formed in September 1792—and though only seven years later republican general Napoleon Bonaparte seized power in a coup—July 14 is remembered as the republic’s anniversary, and is typically celebrated with a big parade in Paris and fireworks.

So what’s Donald Trump got to do with Bastille Day? Why has he flown to Paris for it—other than to see a good parade?

This year, the celebrations will also mark the 100th anniversary of the US’s intervention in World War I. President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany in April 1917, and though America entered the war as an independent power, it collaborated with Britain, France, and their allies. To commemorate this event, president Emmanuel Macron will have Trump as a guest of honor at the parade—then dine him atop of the Eiffel Tower.