Two centuries later, researchers say the French revolution was an act of radical privatization

If you think big government is holding back economic growth today, it’s got nothing on the feudal system of France’s ancien regime. Historians record overlapping levels of nobles and Catholic church officials collecting taxes on everything from passing flocks of birds to the manufacture of doors and windows within city walls, not to mention the all-important growing, milling, and selling of grain.

If you think big government is holding back economic growth today, it’s got nothing on the feudal system of France’s ancien regime. Historians record overlapping levels of nobles and Catholic church officials collecting taxes on everything from passing flocks of birds to the manufacture of doors and windows within city walls, not to mention the all-important growing, milling, and selling of grain.

The resultant economic stagnation is one of the woes that led to the guillotine.

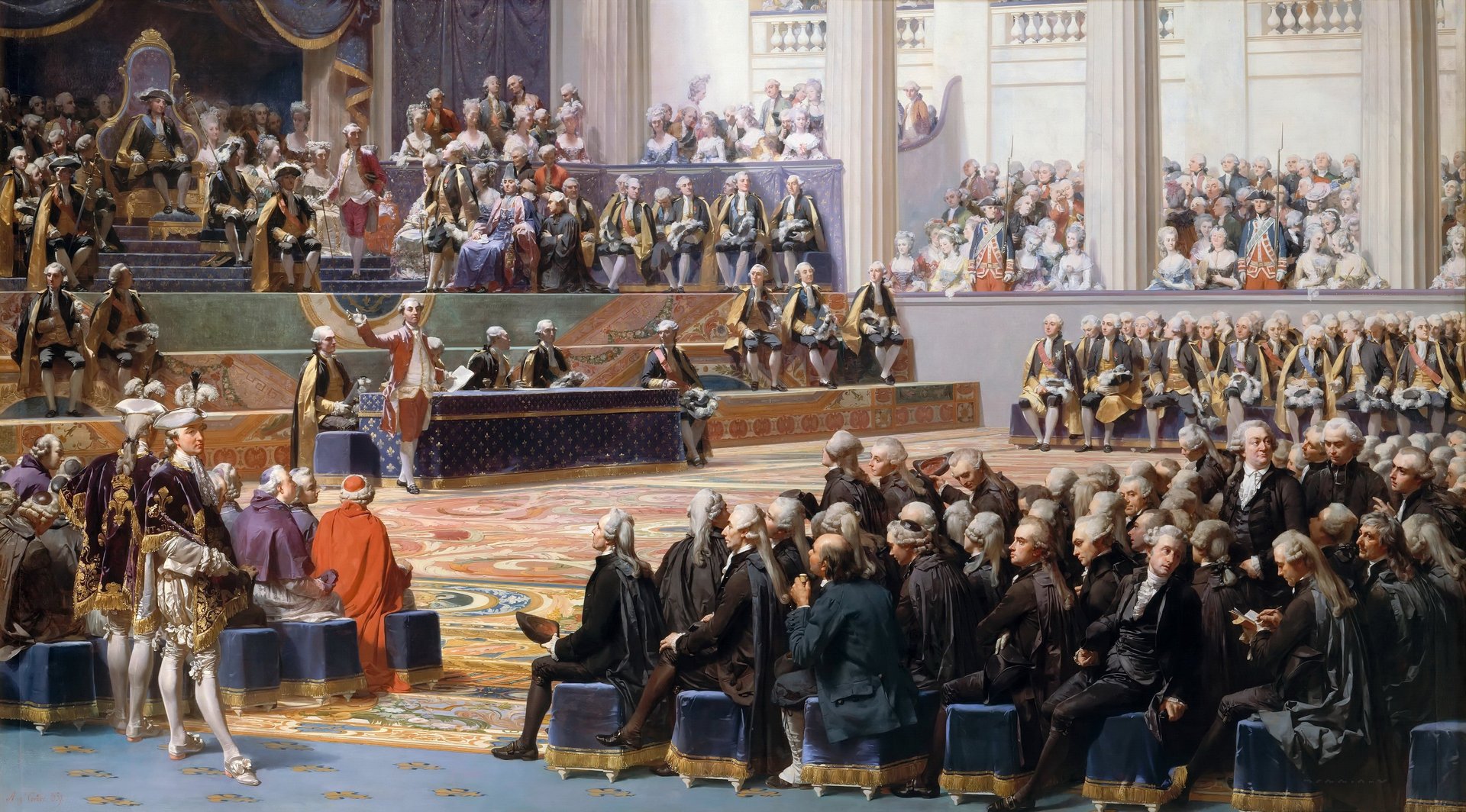

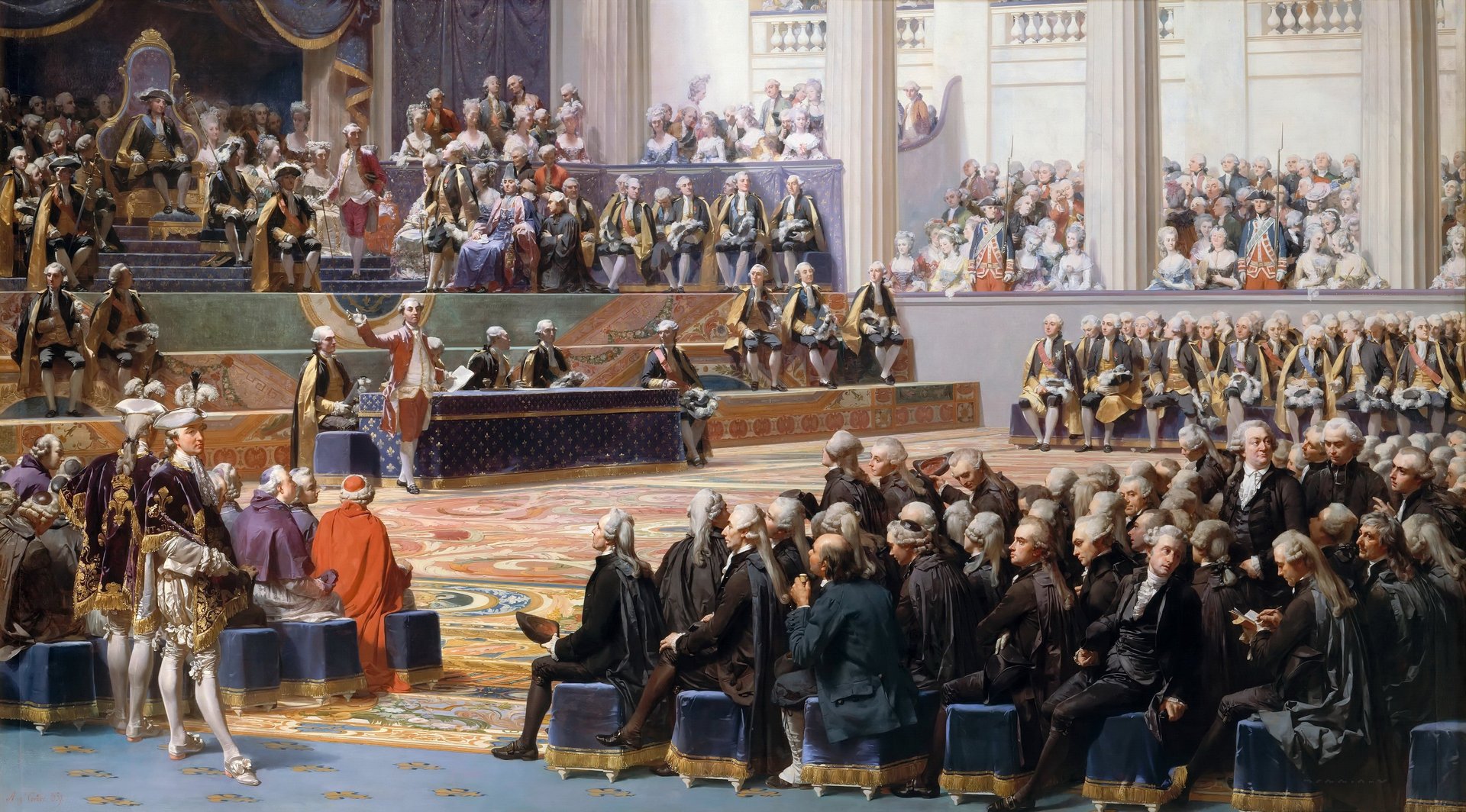

The French revolution, as we were reminded last week on Bastille Day, swept away that feudal structure in the name of liberty, fraternity, and equality. But economic researchers analyzing years of agricultural data argue in a new working paper (pdf) that the economic benefits from this radical turn actually come from increasing inequality and the consolidation of wealth.

In 1789, the revolutionary government seized French lands owned by the church, about 6.5% of the country, and redistributed them through auction. This move provided a useful experiment for the researchers—Susquehanna University’s Theresa Finley, Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Raphaël Franck, and George Mason University’s Noel Johnson.

They tracked the agricultural outputs of the properties and the investment in infrastructure like irrigation, and find that areas with the most church property before the revolution—and thus the most redistribution afterward—saw higher output and more investment over the next 50-plus years. They also found more inequality in the size of farms, thanks to consolidation of previously fragmented land, than in areas with less redistribution.

Why does this matter? The authors argue that this is a case that helps explain one of the most important concepts in economics and law, the Coase theorem, developed from the work of the Nobel-prize winning economist Ronald Coase. The theorem says that bargaining should result in optimal outcomes regardless of how economic institutions are designed. However, the lack of perfect bargains in the world led economists to refine this prediction—these optimal outcomes only happen when there are no transaction costs. In reality, the high costs of making a deal often block mutually beneficial deals.

Consider French agriculture: Before the revolution, large landholders like the church tended to focus on renting out their land to small-holders, but these small plots didn’t reward investment in large-scale irrigation or other improvements, especially since feudal authorities would collect much of the results. They also faced numerous legal obstacles to selling their land to someone who might invest in it. The system put too many costs on smart investments to be effective.

After the revolution, feudalism was abolished, and eventually a modern civil code was imposed under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1804. But this didn’t necessarily result in efficient reallocation of land—legal uncertainty, attempts to retain ownership by former feudal lords, and a generally stodgy local bureaucracy all made transactions difficult. It wasn’t enough to change the rules without changing the existing power structure.

The one place where ties to the past system were purely cut was with the auctions of lands formerly held by the church, which were sold to private speculators in one fell swoop.

“The auctioning-off of Church land during the Revolutionary period gave some regions a head-start in reallocating feudal property rights and adopting more efficient agricultural practices,” the researchers conclude. “The agricultural modernization enabled by the redistribution of Church land did not stem from a more equal land ownership structure, but by increasing land inequality.”

In other words, this research argues that radicals who wanted to do more than simply abolish feudal privileges, but actually redistribute the land itself, had an economic point: Without reallocating resources directly, it seems it took far longer for revolutionary reforms to take hold and the advantages felt in areas with more redistribution to subside.

At the same time, the study is also a reminder that markets can be an effective way to promote development, even when you’re overthrowing your overlords.