Inside China’s crazy plan to build the longest, most expensive, most dangerous underwater tunnel on the planet

Deep beneath the Bohai Sea, Chinese engineers may soon begin boring the longest submarine tunnel on the planet. At an estimated 76 miles (123km) long, it would surpass the combined length of world’s two longest underwater tunnels—Japan’s Seikan Tunnel and the Channel Tunnel between the UK and France. To connect the bustling northern ports of Dalian and Yantai, the engineers will have to tunnel through two fault zones that have caused a slew of deadly earthquakes in the last century. And the project will cost a whopping $42.4 billion (paywall), nearly three times as expensive as Boston’s Big Dig.

Deep beneath the Bohai Sea, Chinese engineers may soon begin boring the longest submarine tunnel on the planet. At an estimated 76 miles (123km) long, it would surpass the combined length of world’s two longest underwater tunnels—Japan’s Seikan Tunnel and the Channel Tunnel between the UK and France. To connect the bustling northern ports of Dalian and Yantai, the engineers will have to tunnel through two fault zones that have caused a slew of deadly earthquakes in the last century. And the project will cost a whopping $42.4 billion (paywall), nearly three times as expensive as Boston’s Big Dig.

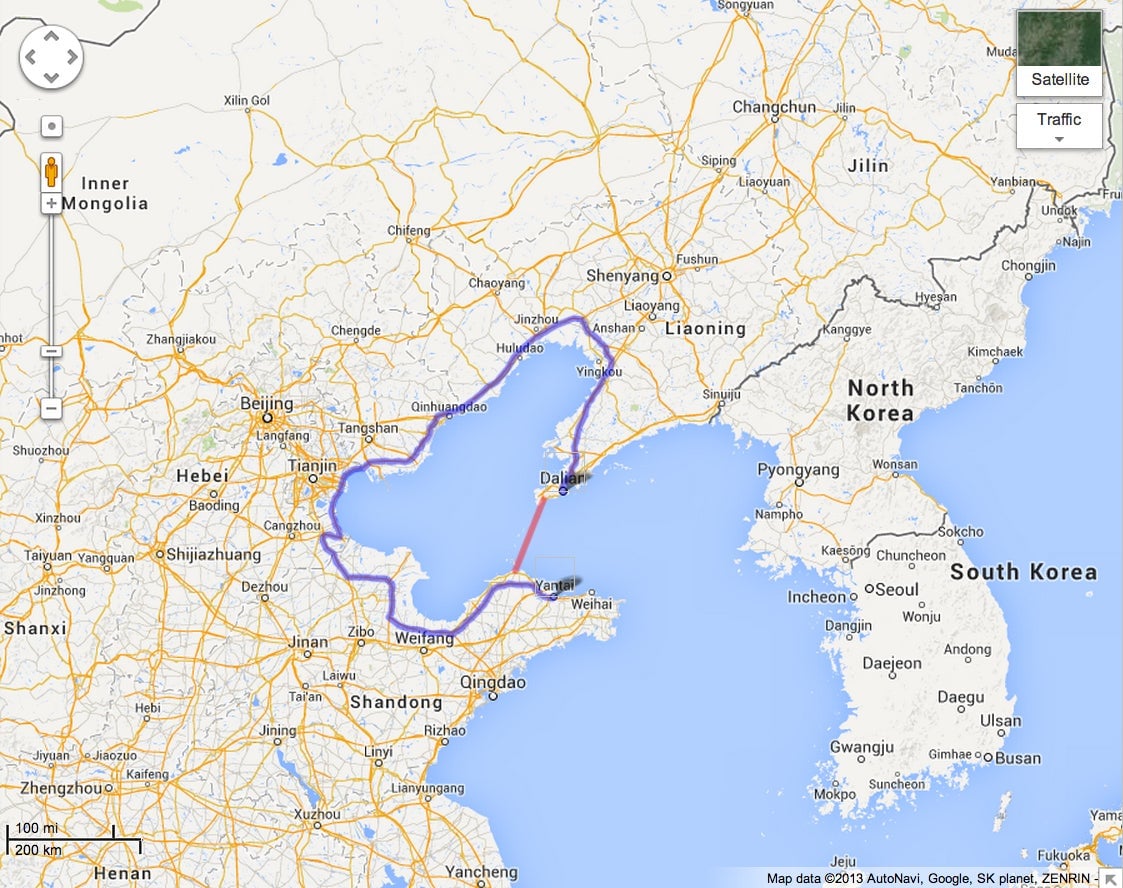

Though only 105 miles apart as the crow flies, the drive between Dalian and Yantai takes around seven to eight hours. The Bohai Tunnel would shorten that to an hour. The State Council will begin reviewing the completed blueprint for the tunnel as early as next week.

Provincial leaders of Shandong and Liaoning hope the tunnel will stimulate economic growth by connecting China’s northern rustbelt region with the upper reaches of the wealthy eastern coast. A member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering projected annual revenue of $3.7 billion, largely from freight, meaning the project would potentially pay for itself in 12 years. And if that’s not rationale enough, there’s bonus of claiming another world record (the government seems to have a fondness for superlative infrastructure).

Compared with the world’s other undersea tunnels, though, this one is massively ambitious. Here’s why:

It’s long

The Bohai Tunnel’s 76 miles would make it twice as long as both the current record-holder, Japan’s Seikan Tunnel, between Hokkaido and Honshu, and the Channel Tunnel, sometimes called the “Chunnel.” That’s a lot of ground that the geographical survey has to cover to make sure the tunnel is feasible.

It’s deep

As it happens, Chinese engineers already have some experience with underwater tunnels. The 3.8 mile-long Jiaozhou Bay Tunnel connecting Qingdao and Huangdao, was completed back in 2011, and the Xiamen tunnel was completed in 2010.

Those projects used one of the more common ways to build an underwater tunnel, the “cut-and-cover” method. This entails dredging a trench in the ocean floor and embedding sealed tube sections made of steel or concrete. After divers connect and seal the tube sections, the water is pumped out of the resulting passage and the upper half of the tube is covered with rock. This is how one of the Big Dig tunnels beneath Boston Harbor was constructed.

Given that the Bohai Bay is roughly the same depth the Jiaozhou Bay, the “cut-and-cover” approach might work. However, the Bohai Tunnel is 20 times longer than the Jiaozhou Tunnel. That means the Bohai Tunnel will likely require more sophisticated—and expensive—technology than that used for the earlier Chinese submarine tunnels. If the seabed is sufficiently soft, the tunnel can be made the way land-based ones often are, using massive drills called tunnel-boring machines (TBMs).

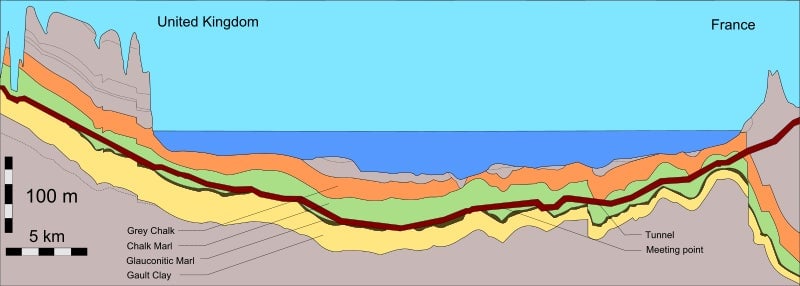

These things are huge. The TBMs used on the Channel Tunnel—or “Chunnel,” as it’s known—were two football fields long and could drill 250 feet a day.

The way it works is that two TBMs on opposite sides of the waterway gouge through the sea floor until they meet in the middle. Here’s a cross-section of the terrain that the Chunnel engineers had to bore through (evidently the UK TBMs bore faster):

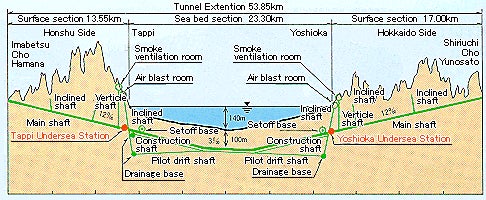

While the Channel Tunnel’s deepest point is 75 meters beneath the surface of the ocean, the Seikan Tunnel is 240 meters down—beneath 140 meters of water and another 100 meters of seabed, which made things tougher for Japanese engineers.

But it’s not just depth per se that matters. In conditions in which the rock hardness varies a lot, TBMs can be dangerous and ineffective. Though the Japanese first tried using TBMs, the variable type of rock in the seabed caused them to abandon this method in favor of 2,800 tons of dynamite. This is called the “drill-and-blast” method. Here’s the blueprint the Seikan Tunnel engineers followed:

This method may be somewhat riskier than the other two, on balance. For instance, a slew of leaks during construction on the Seikan Tunnel led to financial losses and killed four workers. At one point, workers blasted into an area with softer rock, causing water to flood the tunnel at a force of 80 tons per minute. For what it’s worth, both of the two previous Chinese underwater tunnels used the drill-and-blast method.

It will have to withstand 8.0-magnitude earthquakes

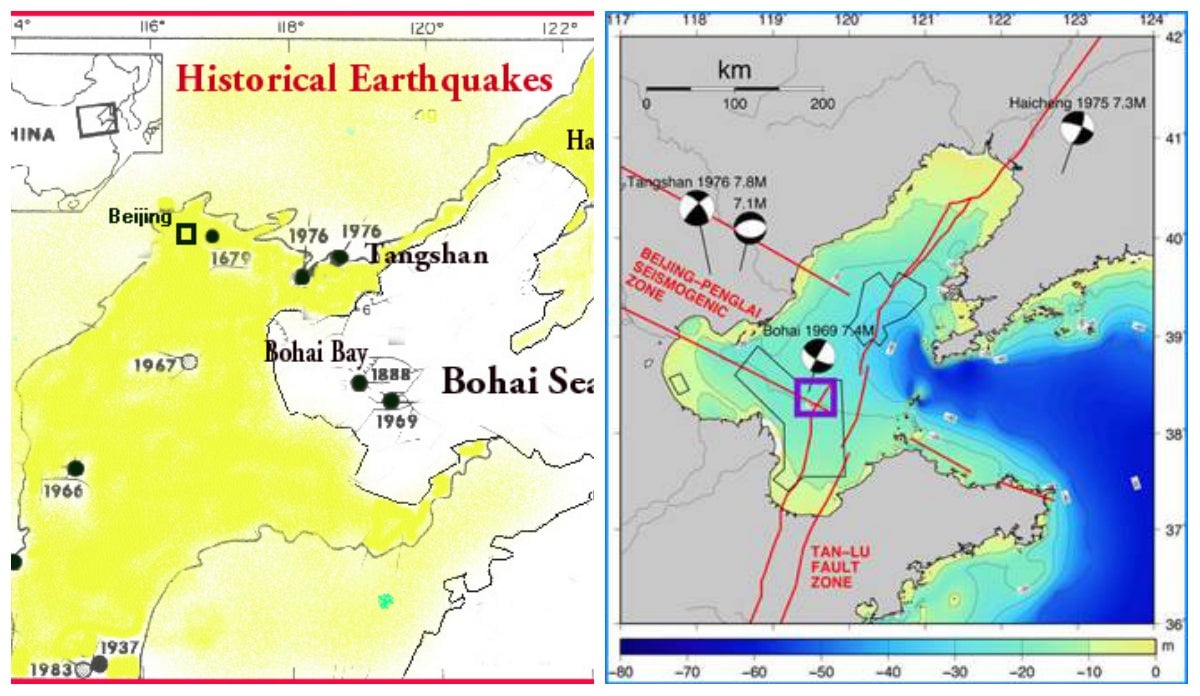

But depth and length are only part of the challenge—the Bohai Tunnel also will need to plan around two major fault zones:

Throughout modern Chinese history, the Tanlu and Zhangjiakou Penglai fault zones have been the source of chronic seismic activity. The 1976 Tangshan earthquake, which killed between 250,000 and 650,000 people, is the most notorious, though as you can see in the map above, there have been others. Perhaps the most concerning historical earthquake for the tunnel engineers to consider is the 7.4-magnitude quake of 1969 that occurred under the bay itself.

What exactly is there to do about it? Li Sangzhong, a maritime geology professor at Ocean University of China, told Caixin that the solution was simply to reinforce the strength of the tunnels walls so that it could “withstand at least a magnitude eight earthquake.”

And it’s expensive

Fortifying a huge underwater tunnel against the kinds of earthquakes that fell whole skylines will be pricey. The provincial governments of Shandong and Liaoning are reportedly kicking in a combined $16.3 billion. But the price is already beyond what they can afford. Worse, these tunnels almost always go over-budget—the Chunnel, Seikan and the Big Dig are just a few examples.

The tunnel’s enormous pricetag makes the timing a little awkward. Vexed by mushrooming sums of local government debt, the central government has been making noise about reining in stimulus spending.

But the Bohai Tunnel isn’t necessarily a wasteful vanity project of a local government official (though it certainly could be). Despite the desperate need to hit GDP targets, local officials—particularly those of struggling provinces like Liaoning—have increasingly limited options for developing their economies. Linking up China’s isolated rust belt to the rest of the country’s trade and logistics channels could flush wealth beyond China’s affluent eastern coast. But the unfortunate thing about boring a long, gigantic hole under a bay and through two fault zones is that there aren’t really any precedents to go by.