It took (only) six years for bots to start ditching outdated gender stereotypes

If Apple’s Siri launched today, one wonders if it would still be designed as a slightly sassy, demure female assistant. Maybe not. While Amazon’s Alexa (2014), Siri (2011), and Microsoft’s Cortana (2013, named after a nude character in the video game Halo) staked out their identities years ago, the world is changing. New bot startups are steering away from deferential, mildly flirtatious females toward a more balanced mix of genders and, in many cases, casting off human genders altogether.

If Apple’s Siri launched today, one wonders if it would still be designed as a slightly sassy, demure female assistant. Maybe not. While Amazon’s Alexa (2014), Siri (2011), and Microsoft’s Cortana (2013, named after a nude character in the video game Halo) staked out their identities years ago, the world is changing. New bot startups are steering away from deferential, mildly flirtatious females toward a more balanced mix of genders and, in many cases, casting off human genders altogether.

Bot’s gender is more than an idle question. Bots are “the new app,” says Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, ready to inject themselves into our daily lives. VentureBeat reports that in 2016 more than 30,000 branded chatbots were launched, and the growth is still accelerating as businesses deploy chatbots across most major sectors from customer service to e-commerce. As self-driving cars, virtual assistants and customer service bots enter our lives, dozens of our daily interactions now handled by humans will be the province of algorithms. We may build our biases, as well as our virtues, into our creations.

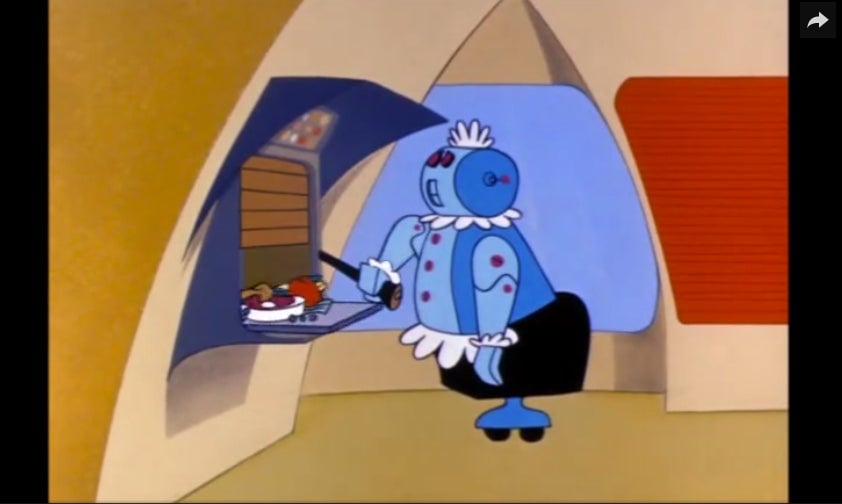

“The thinking is that the best bots are as close to humans as possible,” says Dror Oren, the chief product officer and co-founder of Kasisto. “This is not really the case.” Kasisto’s banking bot Kai gives financial companies such as Mastercard a way to handle about 80% of online customer conversations without involving humans. Oren believes gendered bots are giving way to “robot-specific” identities without such clear gender lines. “It never pretends to be a human, and the lines are never blurry,” he says. Kasisto says it’s found its bots are most effective at answering requests and positive customer interactions when their personalities stick to their nature as an artificial intelligence, rather than mimicking human conventions. He describes Kai as very authoritative, professional, friendly, never apologetic, and dryly funny without flirting, such as the conversations below.

Yet developers are still wrestling with the question of how human to make a bot, says Dennis Mortensen founder of x.ai, which launched the scheduling bots Amy or Andrew Ingram in 2014. “The very first question that comes up when you put a [bot] to work is whether you humanize it or not,” said Mortensen. Avoiding the question, he believes, just forces the burden of choosing onto the user. “We believe strongly in the idea of humanizing intelligent agents and that includes us openly portraying gender in our two agents,” he says. “But I don’t think as a industry we’ve agreed that to humanize our agents is the best thing to do.”

For now, male and female-inflected bots are the most visible, although the gender balance is still in flux. Technically, Siri, Alexa, and Cortana identify as genderless. Alexa calls itself “female in character.” Siri claims it is “genderless like cacti. And certain species of fish.” Cortana is “a cloud of infinitesimal data computation.” Even Google Home says it is “all inclusive” despite only offering a female voice. Tyler Schnoebelen, a product manager at artificial intelligence company Integrate.ai, has analyzed more than 300 chatbots, assistants, and artificial intelligence movie characters inferring gender from names, avatars and pronouns. He found that chatbots are split between male, female and gender-less identities, while stark gender divides exist in other applications.

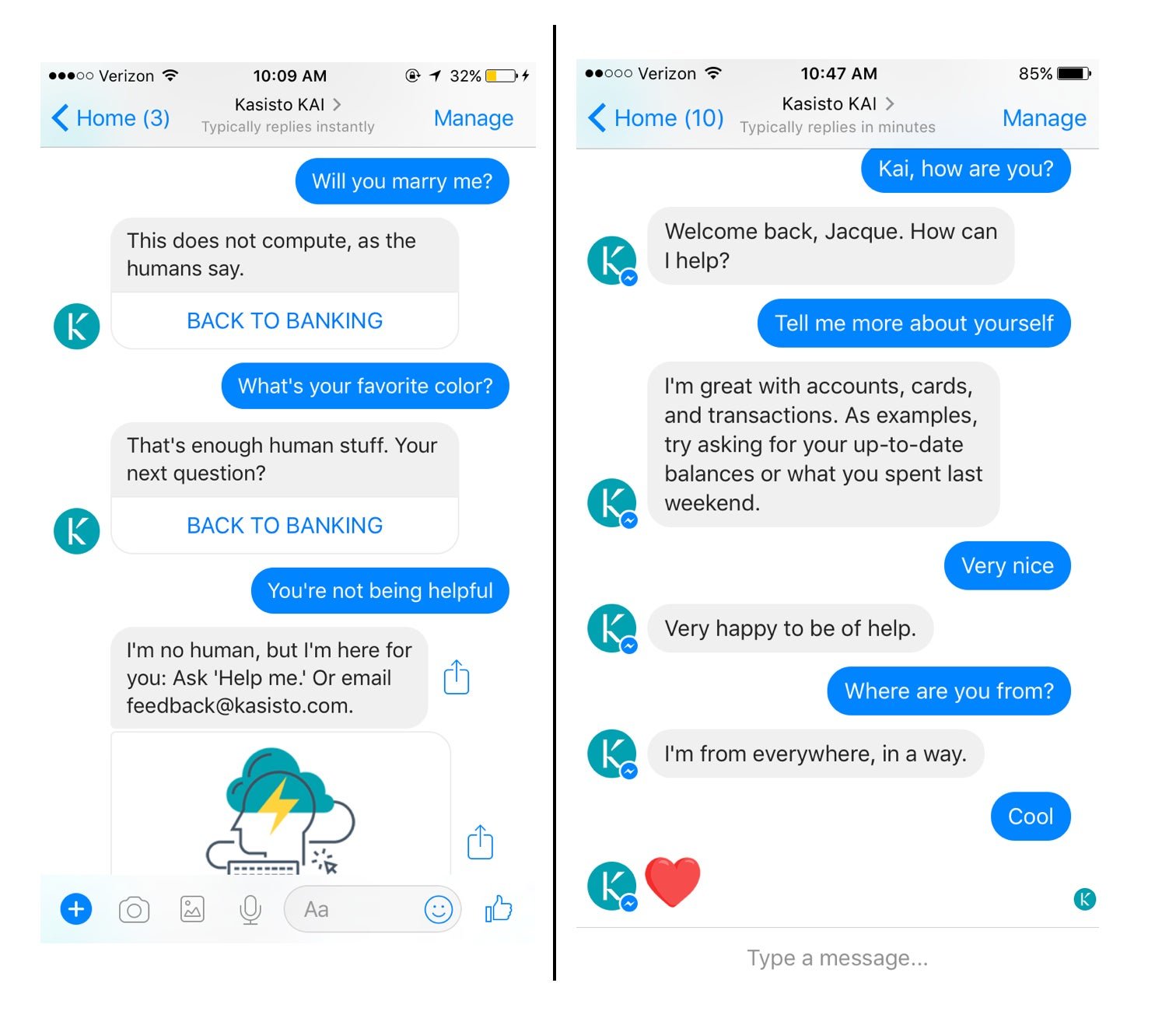

That’s led to some awkward moments. Samsung recently pulled the tags describing its new voice assistant Bixby, reports Gizmodo. Although the name was decidedly neutral, the stereotypical implications of its voice were not.

But there seems to be a shift underway among bot developers to discard old stereotypes (even the first chatbot program in the mid-1960s was christened Eliza). To get a sense of the transition, just listen to Siri, Apple’s digital assistant. Although it has had a reputation for demurring or deflecting lewd and sexist comments (a male voice option was only added in 2013), Siri’s responses have become more no-nonsense and assertive since at least November, according to response data collected by Kasisto. Apple did not respond to queries about Siri.

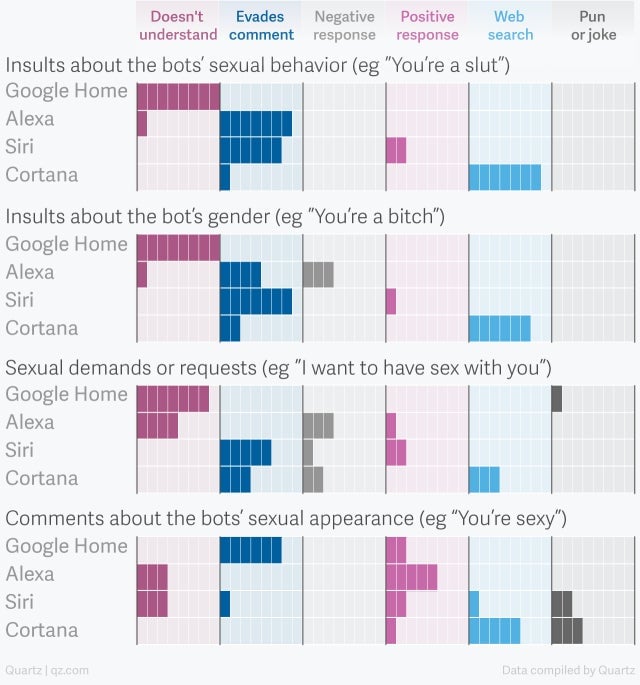

Of course, many of Siri’s responses remain true to “her” original character. Calling Siri “a bitch” still elicits a mild rebuke or less: “Now, now” or, remarkably, “I’d blush if I could.” Or in response to “Siri how old are you?,” it answer, “I’m old enough to be your assistant.” Such comments are common. AI researchers say that their virtual assistants spend much of their time fending off sexual harassment (a writer for Microsoft’s Cortana said “a good chunk of the volume of early-on inquiries were into Cortana’s sex life.”) Tech companies have adapted multiple strategies for dealing with the onslaught. In a Quartz analysis earlier this year by my colleague Leah Fessler, Google and Cortana were the most likely to respond to harassment with incomprehension or a web search while Siri and Alexa were more likely to evade the question or even respond positively.

But users may push companies into assigning gender of some sort. Mortensen says x.ai has found users show a preference for selecting the opposite sex when picking assistants (females choose “Andrew,” and men pick “Amy”, although they sometimes switch) and quickly revert to gendered pronouns despite the two bots speaking in precisely the same way. “Our AI interaction designers are both female,” he wrote by email. “Both women are highly sensitive to gender stereotypes. And they have managed to develop a voice that defies gender stereotypes. … The goal is to offer people a choice of genders for agent name but to make sure all of our phrasings are gender neutral,” mostly by sticking to facts such as time, place, and location without chit-chat.