Unfamous Valley: Why it sucks to be not quite famous

I recently changed my Twitter profile to include the following: “End User Agreement: Euny will read your tweets for US $20. Tweeting to her will be interpreted as an agreement to pay her.”

I recently changed my Twitter profile to include the following: “End User Agreement: Euny will read your tweets for US $20. Tweeting to her will be interpreted as an agreement to pay her.”

Why did I have to do this? Because I am Unfamous (not to be confused with Not-at-all-famous) in the least famous, least enjoyable of all celebrity categories: published author. I’m famous enough to be at the receiving end of insults by entitled, resentful strangers who want me to know that their unwritten, theoretical book inside their head is better than my actual books. But I’m not famous or rich enough to get the protections against weirdos that real celebrities can afford, such as having someone read your insults for you.

Most of my public appearances are in bookstores, which tend not to have bouncers, even though there’s always some creep at these events who doesn’t buy any books yet tries to monopolize the autograph queue.

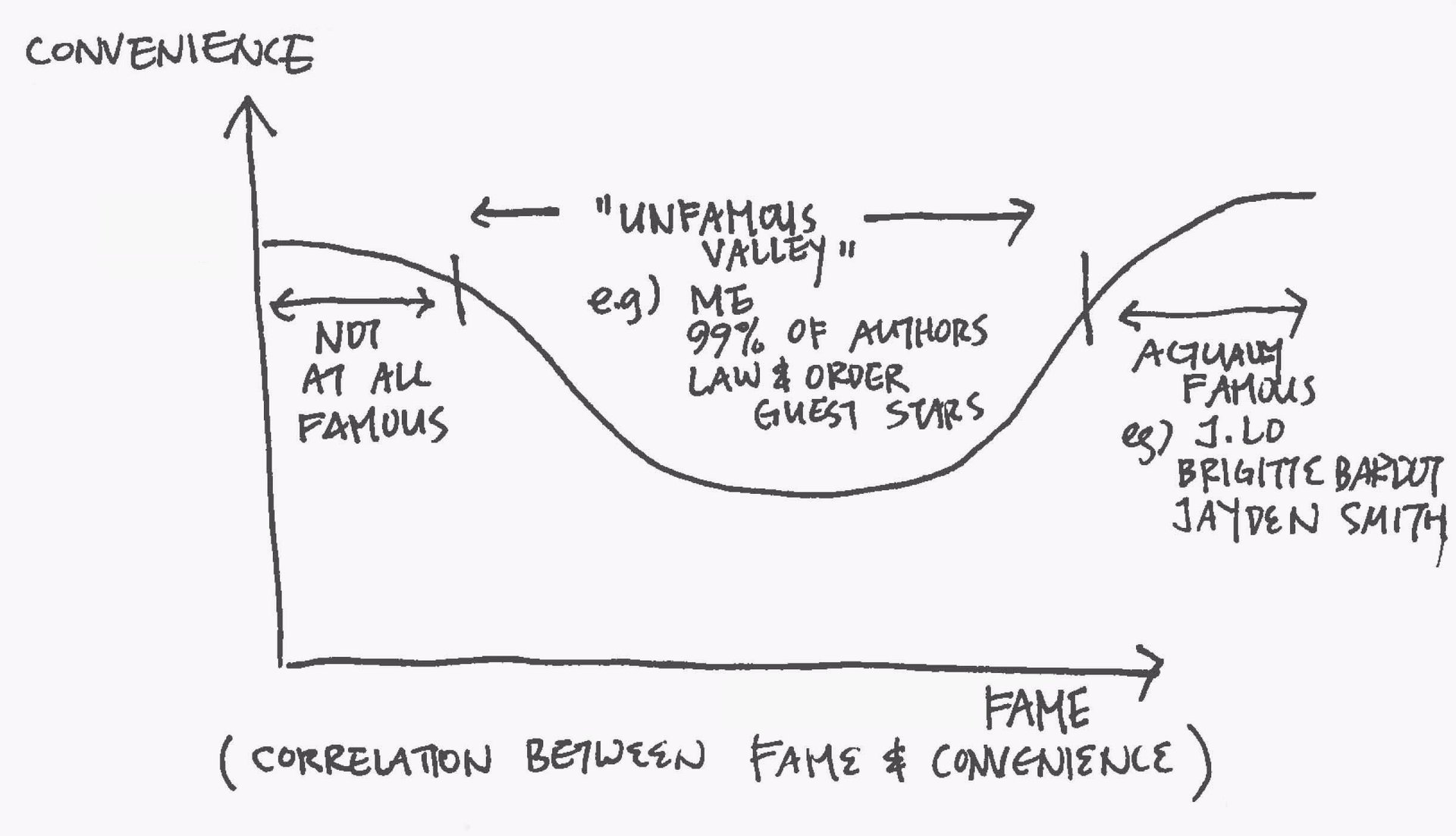

I dwell in a horrid place I like to call “Unfamous Valley,” an intermediary stage where you are neither fish nor fowl. Some people emerge from this purgatory to become truly famous and get enough perks to compensate for the lack of privacy—chauffeured cars with tinted windows, literally and metaphorically speaking. Most of us, however, live forever in this Sartre play where we are broke and yet don’t have the right to be left alone.

So how Unfamous am I? Pretty close to the left end of that valley. I wrote two books; one was a too-clever-by-half “comedy of manners” that sold poorly. In tone, it resembled a less-clever version of Lena Dunham’s HBO series Girls crossed with Jane Austen, except with more Asian people. The second, called The Birth of Korean Cool: How One Nation Conquered the World through Pop Culture (Picador 2014), got me a fair amount of attention, but I wasn’t able to enjoy the success. As with most writers in Unfamous Valley, the exigencies of the market forced me to become an expert on a subject in which I have no interest: Korean pop culture. Often I feel like Brian Wilson, front man for the Beach Boys. He famously hated surfing, but for commercial reasons he used the word “surf” or “beach” in nearly every song. Only after spectacular mainstream success was he allowed to make the experimental, revolutionary Pet Sounds album. I may never get to make a Pet Sounds.

I know I don’t have much to complain about, but when you take into account my agoraphobia and my hatred of doing things for free, perhaps my existential annoyance with Unfamous Valley starts to make more sense. If you’re about to be published, consider this a PSA. Here be the perils:

1. People want you to debate with them on social media for free, and they get mad when you don’t. Guys, this is panhandling. I don’t write unless I’m getting paid, and just because you do it, doesn’t mean I have to.

2. People ask you for free books. Again, panhandling. Those who would never dream of asking me for money have no qualms about asking me for free copies of my book. I’ve made this handy flow chart that I send to people when they make such requests:

3. People who have never written anything but have “this great idea for a book” ask you to write books “with” them, when they really mean “ghost-write, unpaid, using your contacts to get it published.”

This is offensive for several reasons. First, the harassers overestimate the value of their idea and pooh-pooh the act of execution as a mundane task that they don’t have time for.

Second, the ideas themselves—oy. Third, the rude way that they word the request makes me feel embarrassed for their parents.

Here are some actual ideas people have sent me:

From an email received from a stranger: “I have an idea for a novel, called [TITLE REDACTED]. I have no literary ability.” He explains he wants me to write the whole book (which takes place in the Ukraine) based on his outline. He tantalizes: “Subject to final confirmation on both sides, should you agree to take on this project, all I ask for in exchange are the rights to translate the completed novel into French and into Spanish, nothing else.” [emphasis mine]

I was approached for a “collaboration” by some Beth person I met once at a party, who was one of these filmmakers who hasn’t done anything except have business cards professionally printed. Her email proposed we co-write “a novel about the creator of bitcoin being, in fact, AI. What a great premise.” [Beth’s self-praise was in the original]

I politely declined, but she wouldn’t take no. She wrote back: ”Having another writer off of whom I can bounce ideas would be helpful. Maybe we can still work together in that capacity.” People, the expression “No means no” applies to people’s time as much as it does to their bodies.

Then there was the guy who pitched me a book about a gay ghost. This is how I learned that you should never trust a writer who ends a pitch with “And then things get complicated.”

If you’re offended that I would be sharing people’s ideas in a public forum, hurrah; that’s the point. Don’t send me your dumb ideas. Best-case scenario, I reprint them. Worst-case scenario, I share them with the very next writer I bump into who tells me that they have writer’s block and that they need an idea for a story.

4. Random people from your past show up to your readings and pretend they found out about them while Googling something unrelated.

5. I get invited to do a lot of speaking engagements. Their initial offer is usually zero dollars. I punt these requests to my speaker’s agent, who has informed me that at least one such party asked her why I wanted to be paid.

It was actually my speaker’s agent who shed light on why people harass authors, even the Unfamous ones. “People feel like they know you,” she said, and thus feel entitled to make demands: Familiarity breeds contempt, etc. Guys, the Unfamous are people too. I’m sorry no one ever taught you any manners, but that’s not my problem.