Japan’s “vagina artist” is back and raising the alarm on prison conditions

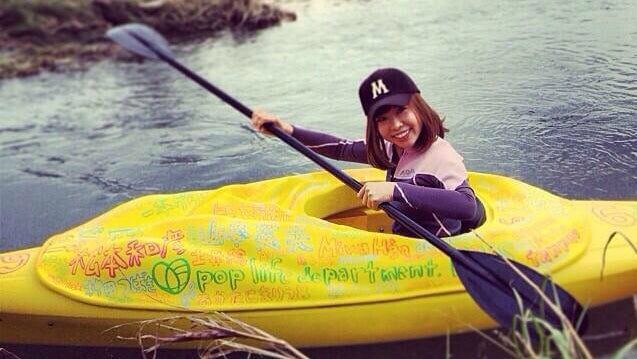

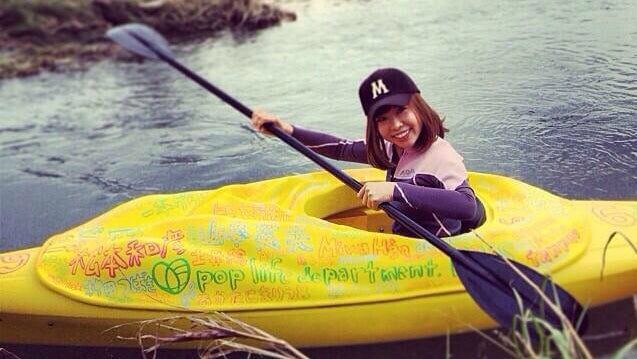

Japanese artist and activist Megumi Igarashi, most famous for 3D printing her vagina in order to build a genitalia-shaped kayak, is stepping up her political activism now that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s controversial new anti-terrorism law has gone into effect, over the protests of thousands. Ahead of its passage, Igarashi tweeted in May that “the new law may in future jail the innocent” and urged people to play her game of cards to learn about interrogation and prison.

Japanese artist and activist Megumi Igarashi, most famous for 3D printing her vagina in order to build a genitalia-shaped kayak, is stepping up her political activism now that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s controversial new anti-terrorism law has gone into effect, over the protests of thousands. Ahead of its passage, Igarashi tweeted in May that “the new law may in future jail the innocent” and urged people to play her game of cards to learn about interrogation and prison.

It’s a new focus for Igarashi, also known as Rokudenashiko (which translates to “good-for-nothing girl”), who has long been conducting an intense campaign to break the taboo on the depiction of the female sexual organ in Japan.

Local anti-obscenity law has most frequently affected film-makers and manga artists (here is a good summary in English of the reach of the law; warning: some explicit images), but Igarashi’s work also points out how selective—and sexist—its application is. Distributing the 3D data of her vulva to her Kickstarter backers put her in breach of the law and brought her briefly behind bars in 2014, but other genitalia-themed events haven’t fallen foul of the regulation. A major case in point, traditions like Kawasaki’s Kanamara Matsuri, or “Festival of the Steel Phallus” in which a large pink penis is paraded in the streets and penis-shaped snacks and souvenirs are openly purchasable. Phallic-shaped stones are a regular occurrence in Shinto temples, supposedly linked to fertility rituals.

Igarashi’s brush with the law ended with an acquittal on obscenity for the kayak, but a fine of 400,000 yen (about $3700) for distributing the digital files related to the 3D printing—deemed to be “obscene material.”

As Igarashi continues her campaign to make mankos (Japanese for vaginas) an acceptable part of artistic endeavor, she has also joined critics denouncing Abe’s new law, which she warns allows “the government to arbitrarily exert the power of detention over people.”

“People need to know what it means for the government to be able to one day show up at your door and arrest you, like they did to me,” Igarashi told Quartz via email.

Under the new law, actions that seem very far from terrorist plotting can also be punished—like picking mushrooms in conservation forests, copying music, conducting sit-ins to protest against a new apartment building’s construction, or avoiding paying consumption tax.

As this latest threat against freedom of expression and civil liberties enters the legal code, Igarashi has started alerting people to what it means to be arrested by releasing a full set of “game cards” through her Twitter account.

So far, she has published 18 cards, but is planning on releasing 50 – one for each syllable in the Japanese alphabet. The game of cards depicts in manga-like drawings the indignities and hardships of interrogation and serving jail time, from not being given enough items for personal hygiene like Q-tips and toilet paper…

to sleep deprivation due to prison lighting…

…to the fact that while the media covers an arrest extensively, it hardly mentions a prisoner’s release:

In keeping with her style, the “Good-for-nothing girl” has taken an extremely serious topic and is attracting attention to it in a lighthearted manner —yet without softening her criticism of the abuse. The Japanese justice system is notorious for its psychological harshness (paywall): while physical violence is a rarity in the country’s jails, its 99% conviction rate of suspects is obtained through repeated interrogations. Life in prison can involve a lot of solitary confinement and a level of intimidation that has often been criticized by human rights organizations and even by the UN.

Igarashi said she turned to Twitter and playing cards to make the subject more accessible.

“While my jail memoir garnered so many accolades and awards nominations abroad, the book has not done as well in Japan,” she said. “People in Japan don’t want to read books or even manga about the criminal justice system.”

Alerting the public through a playful set of cards might be one more way to sensitize the population to one of Japan’s most serious human rights issues.

The post was updated on July 26 with comments from Megumi Igarashi.