Even with Trump as his boss, there are things the new White House spin doctor can do

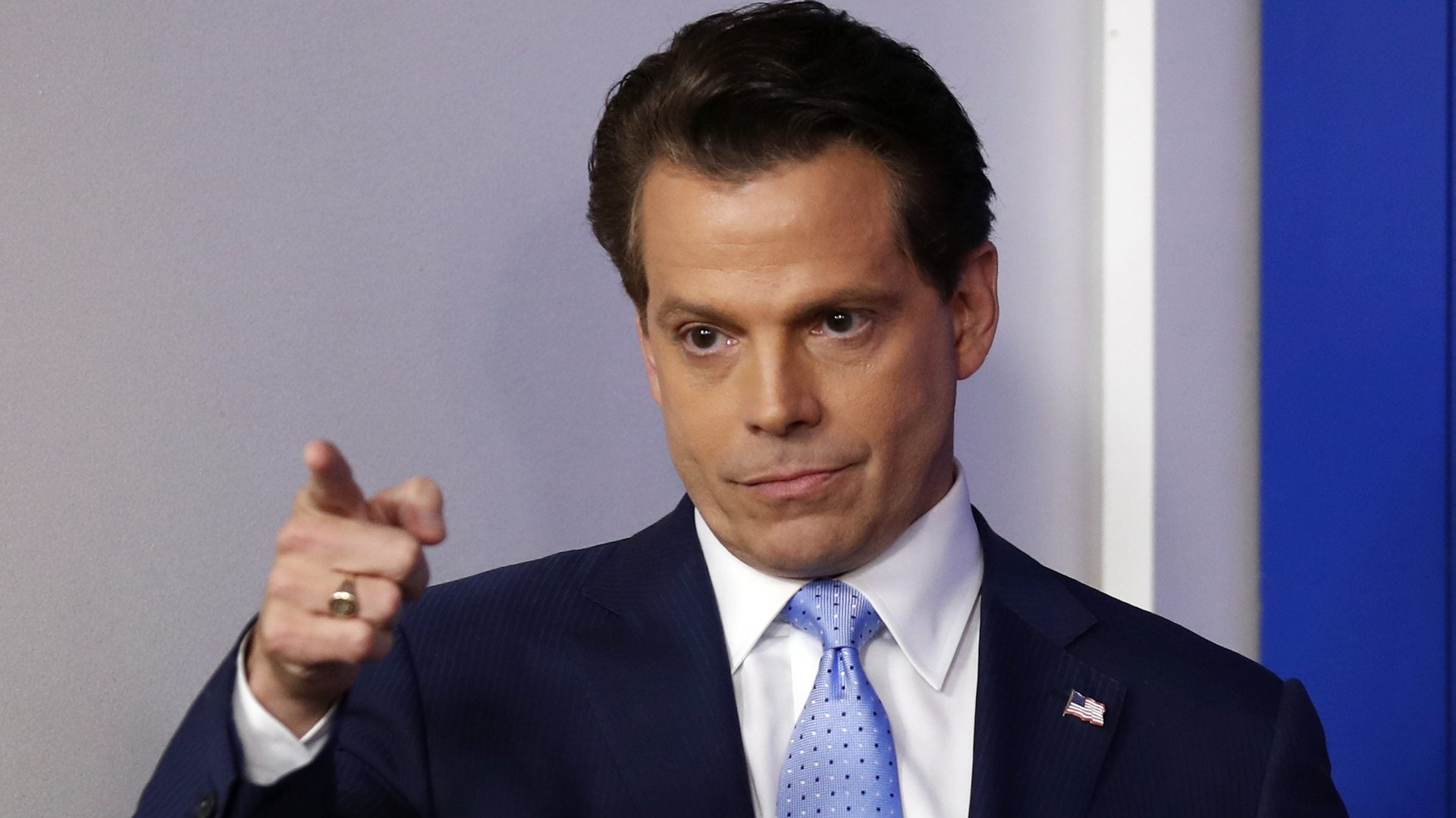

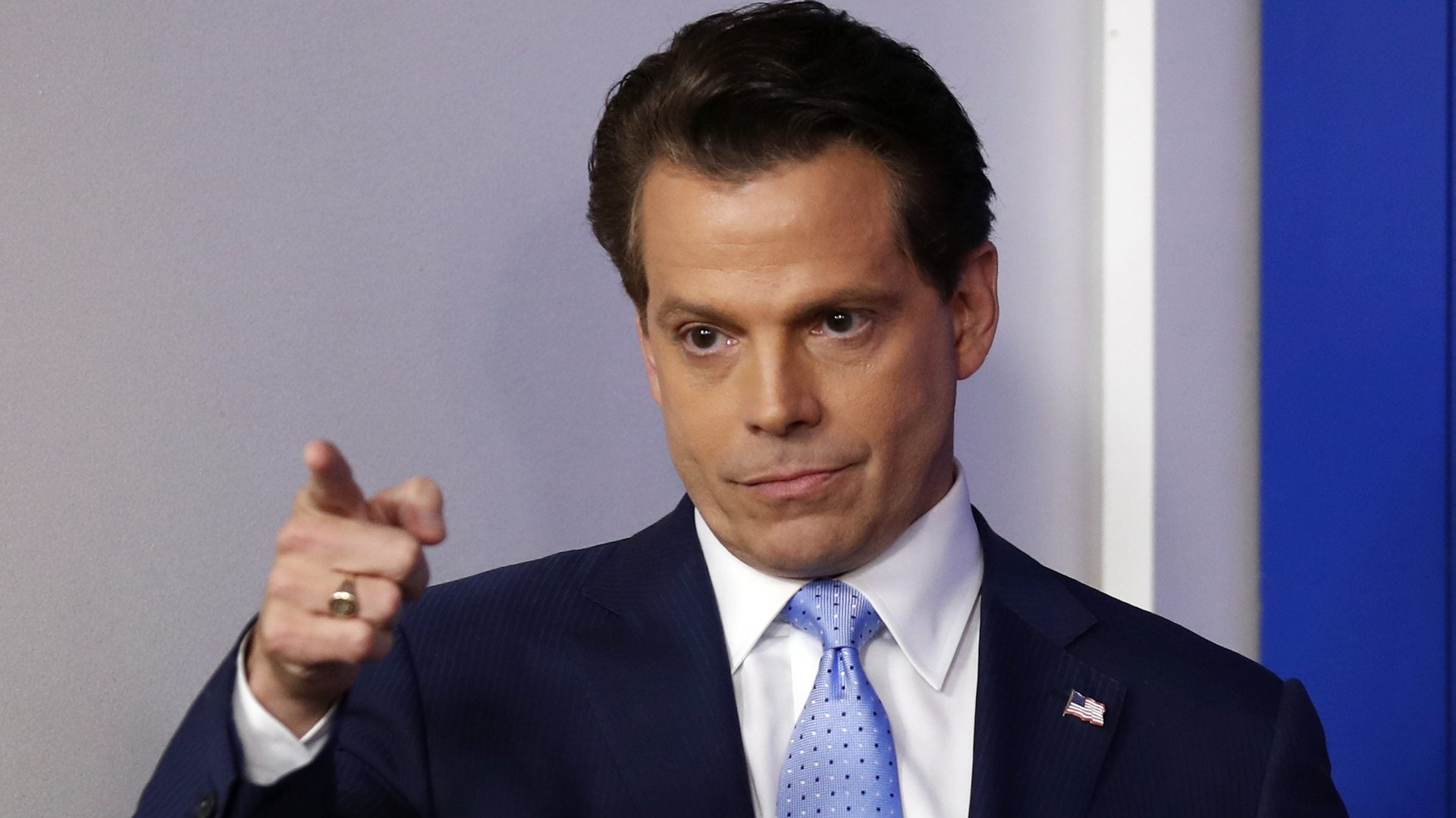

The sport of rugby has a good phrase to describe the job that new White House communications chief Anthony Scaramucci has just been handed: a hospital pass.

The sport of rugby has a good phrase to describe the job that new White House communications chief Anthony Scaramucci has just been handed: a hospital pass.

Scaramucci is the third man to take the job in six months—and neither of his predecessors’ experiences should provide much comfort. Sean Spicer endured one humiliation after another before leaving in a blaze of righteous indignation. Michael Dubke, on the other hand, departed with barely a murmur; many onlookers were unsure quite what he’d done in the role.

“Nobody would have an easy time doing PR for this president,” says Robert Entman, a media and communications professor at George Washington University. “[He] is extraordinarily undisciplined, constantly contradicting himself, stubbornly unwilling to learn about issues, and saying many things reporters know are untrue.”

What’s more, Scaramucci, a finance guy and TV talking head, comes to the job with zero formal experience in public relations and none at all in political communications. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room to turn a terrible situation into a better one. We canvassed four experts, who said these three matters should be top priorities.

Patch things up with the press corps

Spicer’s relations with White House reporters got off to the worst possible start. On day one, he excoriated the press about coverage of the small inauguration crowd, delivering various proven falsehoods. Relations never recovered, with reporters regularly complaining about that he was dismissive and patronizing towards them.

Scaramucci won’t be facing the press every day—that job’s left to Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who is promoted to press secretary—but they will both need to make them feel respected. “[He] can’t repeat the sins of the past, consistently repeating/restating a bunch of blatant falsehoods, undermining his credibility from the start,” said a former senior White House communications official, whose current job doesn’t allow them to comment on the record. “You have to build a strategy that recognizes the president isn’t going to change that much, but the tone of the press and staff side of the White House can and should.”

That means opening up a side of White House communications that has been neglected so far, says David Greenberg, author of Republic of Spin: An Inside History of the American Presidency. “The press secretary’s job is twofold: to represent the president to the press and also to represent the press to the president.” The second part of this job needs a lot of work.

But no matter how hard Sanders and Scaramucci try, Greenberg is unsure they’ll be able to separate irritation with the president from irritation with the press. “I think anyone working for Trump is going to encounter a lot of frustration and in turn is going to pass that on to the press corps,” he said.

Get very close to Trump

Reporters have quickly begun unearthing past statements that could make Scaramucci’s start to the job tricky, such as a 2015 interview in which he called the future president a “hack,” “anti-American,” and an “inherited money dude from Queens County.” But Scaramucci handled it well: he apologized for what he said was the “50th time” at a press conference on Friday and in doing so indicated he and Trump have a good relationship. He told the reporters, with his tongue at least slightly in his cheek, that the president “brings it up every 15 seconds.”

For this task Scaramucci’s lack of a traditional Washington political PR background should help. The two men are cut from the same cloth: smooth-talking businessmen with thick New York accents who pride themselves in never backing away from a fight. Particularly with a president as unpredictable as Trump, those similarities could be invaluable, says Nikki Usher, also a professor at George Washington University’s School of Media & Public Affairs.

“Communications people have to be able to imagine how the person you’re representing is going to think and answer, so he’s bringing someone in who fulfills that position,” she says. “They speak the same language in terms of their business background and are used to dealing with the same types of personalities; so they could have the basis for a common conversation on strategy. That’s powerful.”

Getting that right could stem the excruciating habit of Spicer saying one thing, only for Trump to contradict him later. By contrast, Scaramucci said he actively wanted Trump to take the lead: “The best messenger the best media person in this White House is the president,” he said. “I’m hoping to learn from him.”

Play the Washington game

GW’s Usher says the importance of a communications director having lengthy political PR experience can be “over-emphasized”, but there’s one thing Scaramucci’s resume lacks that there’s no getting away from: “Washington is its own weird beast,” she says. “Just because you know New York and national media doesn’t mean you understand the backslapping, insular culture of Washington.”

Spicer spent years as the Republican National Committee’s spokesman and chief strategist, and takes a wealth of DC knowledge and contacts out the door with him. This administration revels in being filled with outsiders, but Usher says when it comes to messaging it’s crucial to get the capital’s big shots on board. “[These outsiders] don’t know the in-town minor celebrities who are celebrities only in Washington…[and you] definitively respect,” she says. “They don’t understand who’s important or maybe don’t even care.” To get the city’s power-brokers on board, Scaramucci will have to pull out the New York charm that has won over Trump.

Can he steady the whole ship?

The former high-ranking communications official says it’s “possible but certainly not easy.” Greenberg is less sure.

“[He] can help or hurt around the edges, but I think the real issue is what you’re communicating,” says Greenberg, pointing out that Trump has said his messaging efforts have been poor. “When presidents struggle, they like to blame it on bad messaging, because it’s easier than owning up to the idea that ideas or polices or arguments haven’t prevailed in our political struggle…in that sense it’s easy to overstate the importance of the press secretary.”

Bringing on a top new staffer can help turn troubled administrations around, Greenberg acknowledges, noting David Gergen’s addition to the Clinton administration after its chaotic first year, or Howard Baker joining Ronald Reagan’s White House as chief of staff in the wake of the Iran-Contra scandal. But there are two big differences here: First, people who make that big a change would usually be heavily experienced figures joining at a higher level than communications chief. Secondly, the presidents they had to deal with were not Donald Trump. “Trump is so mercurial that it’s hard to have confidence that any advisor would radically change the course of things,” he said.

For the time being, however, Scaramucci sounds confident in the face of his new boss’s abysmal approval ratings. “Sometimes the polls can be wrong,” he said, citing Trump’s unexpected election victory. “The American people are playing a long game, and I think they really, really love the president.”

Tim Fernholz contributed to this report.