There’s a promising new HIV vaccine that can protect against multiple strains at once

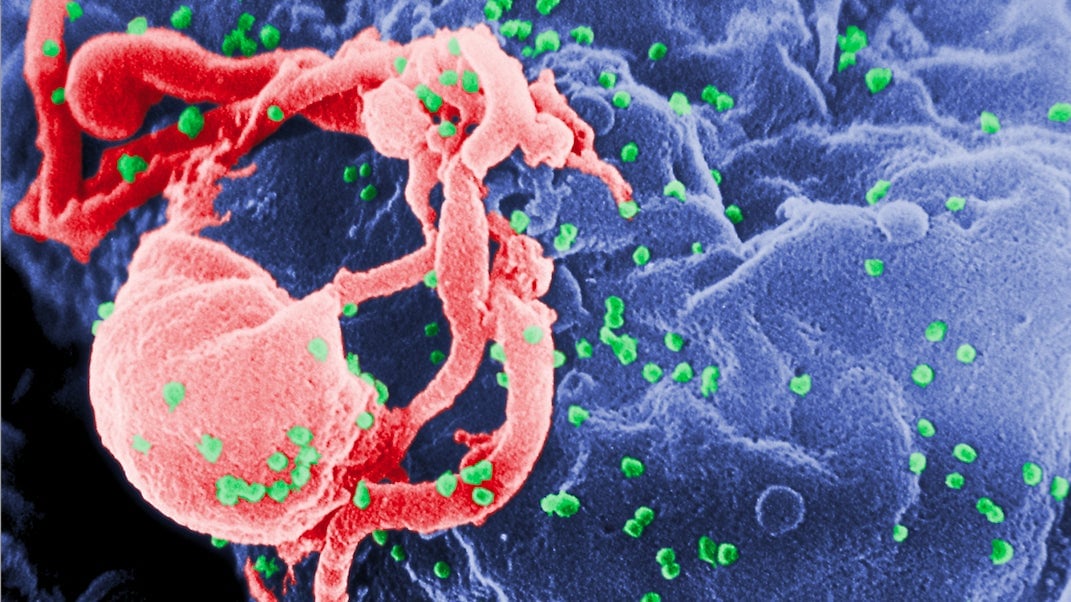

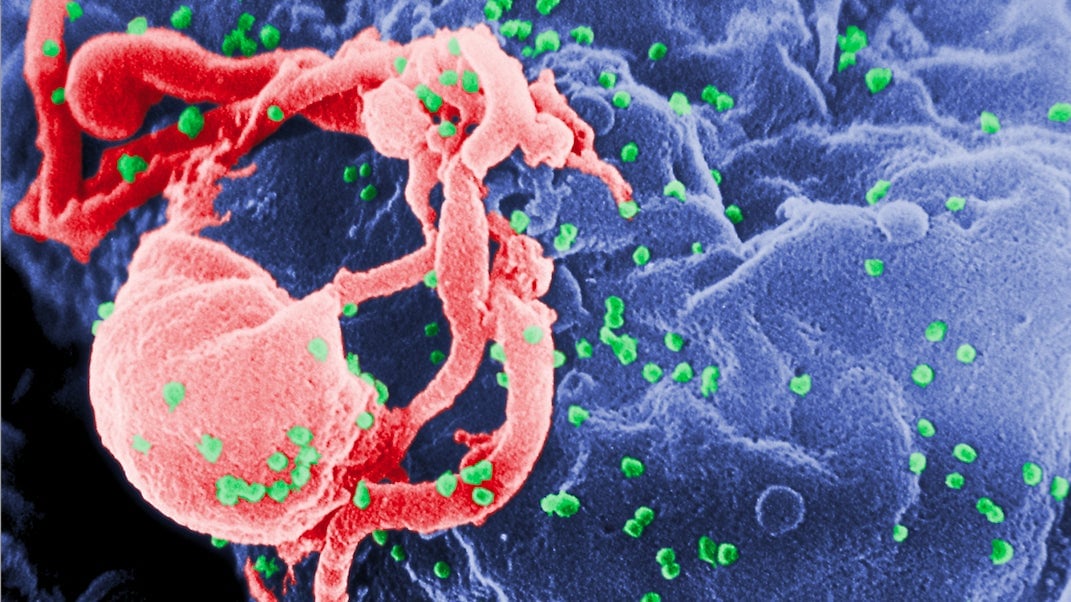

When HIV, attacks the human body, the virus leaves it defenseless in a way that is unlike the body’s response to any other microbial invader.

When HIV, attacks the human body, the virus leaves it defenseless in a way that is unlike the body’s response to any other microbial invader.

Our bodies are smart enough to build up some sort of immune response to almost every pathogen on the planet, says Anthony Fauci, an immunologist and director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). It may take a while, and we may get sick or even die along the way, but before we do we almost always develop a way to fight back.

“HIV is distinctly unique in that the body doesn’t make a good immune response against it,” he says. And it’s because of this that even after 35 years of research researchers have failed to develop a vaccine that works effectively against it.

But today (July 24), researchers from NIAID and Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, which is owned by Johnson & Johnson, reported results from a successful preliminary clinical trial at the International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science in Paris. They study, which was called APPROACH, uses a new kind of vaccine that targets several strains of HIV simultaneously, and appears to not cause any lasting side effects in people who receive it.

Typically, vaccines work by exposing our bodies to some form of an inactive virus or bacteria. In response, the immune system produces antibodies, a chemical response to the invader, as if it were being attacked. Because the vaccine is more or less a powerless shell of the actual pathogen, we never actually become sick. But our bodies remember how to make those antibodies quickly in case of a real infection later on.

The trouble with HIV is that it mutates incredibly rapidly; there are several strains that may infect us (more than even the flu, according to Vox) so we can’t inoculate ourselves against all of them.

To combat this, scientists at the NIAID and Janssen Pharmaceuticals developed a vaccine that takes specific markers from several kinds of strains of HIV and put them all together—like putting on the most distinctive edges of puzzle pieces altogether facing outward. It’s called a mosaic technique, and it theoretically prompts the body to respond with several kinds of defenses that will hopefully be able to fend off many of the variations of HIV.

The specific combination of virus-markers came after researchers tested several against each other. The most successful ones in animal trials—which in monkeys blocked HIV infection 66% of the time after six injections—went into a human study that included 393 people who didn’t have HIV at the start of the trial, living in the US, Rwanda, South Africa, and Thailand.

These volunteers were given one of the seven mosaic HIV vaccines or a placebo to see if they had any adverse side effects. Over the course of four doses (two vaccines and two boosters) over 48 week, participants tolerated the vaccines well. After three injections, most of their blood work showed that their bodies were developing immune responses to HIV—through the presence of antibodies and other cellular changes—which indicate that the vaccine would work against different strains of HIV. The type and strength of this immune response varied depending on which version of the vaccine each person received.

As Vox reports, this is the fifth time an HIV vaccine has reached clinical trials in humans. Three of these approaches have been abandoned because they weren’t successful (researchers shoot for at least 50% efficacy for a vaccine to continue), and the only other ongoing clinical trial is in Thailand which began last November.

Fauci cautions that these results are still preliminary, and further testing in people is needed before any kind of vaccine can be brought to market. Notably, there are plans for a larger clinical trial involving 2,600 women in southern Africa beginning in December 2017 or early 2018. This trial will test the most successful mosaic vaccine for safety and efficacy in the larger sample size.