People have an irrational need to complete “sets” of things

Here’s a tip for persuading people to finish more tasks, buy more products, or donate more money: Simply present assignments, requests, or items as arbitrary sets, rather than as individual units.

Here’s a tip for persuading people to finish more tasks, buy more products, or donate more money: Simply present assignments, requests, or items as arbitrary sets, rather than as individual units.

New research reveals that people are irrationally but effectively motivated by the idea of completing a set, even if it means working harder or spending more money—with no additional reward other than the satisfaction of completion and the relief of avoiding an incomplete set. Imagine arriving at your boss’s summer BBQ and presenting her with five beers in a box designed to hold six. No matter that your favorite craft beer store permits you buy bottles one at a time. Chances are you’d still buy six, just to fill all six spaces in the box.

“People really don’t like to leave things incomplete,” says Kate Barasz, an assistant professor of marketing at IESE Business School and lead author of the paper “Pseudo-Set Framing,” written while she was a doctoral student at Harvard Business School. The term “pseudo-set” refers to the idea that the set is kind of arbitrary—manufactured for the sole purpose of creating the idea of wholeness.

Do you want customers to refer more of their friends to your company’s website? Ask them to refer friends in arbitrary “batches” of five at a time. Looking to increase charitable giving to your nonprofit organization? Ask potential donors to contribute a set of six gifts. Are you and your fiancé struggling to write thank-you cards for all those wedding shower gifts? Try batching the unwritten cards into sets of eight. Rather than feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of writing one note at a time, you’ll feel oddly motivated to finish a whole set at a time.

Appearing in a forthcoming edition of Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, “Pseudo-Set Framing” was co-written by Barasz; Leslie John, the Marvin Bower Associate Professor at HBS; Elizabeth Keenan, an assistant professor at HBS; and Michael Norton, the Harold M. Brierley Professor of Business Administration at HBS.

The Canadian Red Cross puts pseudo-sets to the test

The researchers proved the efficacy of pseudo-set framing through a series of laboratory and real-world field studies.

In one study, they teamed up with the Canadian Red Cross, a humanitarian charitable organization, to find out whether pseudo-set framing could influence gift-giving behavior during its 2016 holiday online fundraising campaign.

More than 7,000 potential donors were randomly (but evenly) directed to one of three landing pages.

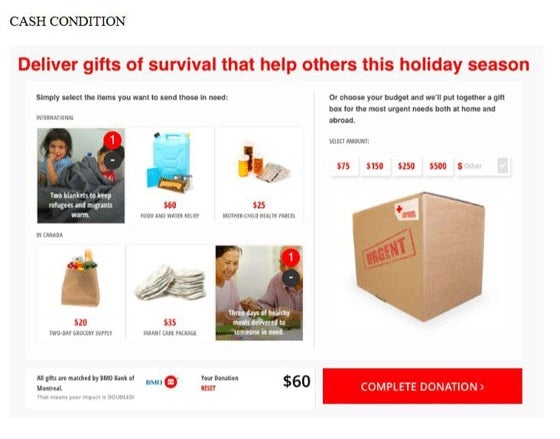

The first page emphasized cash donations.

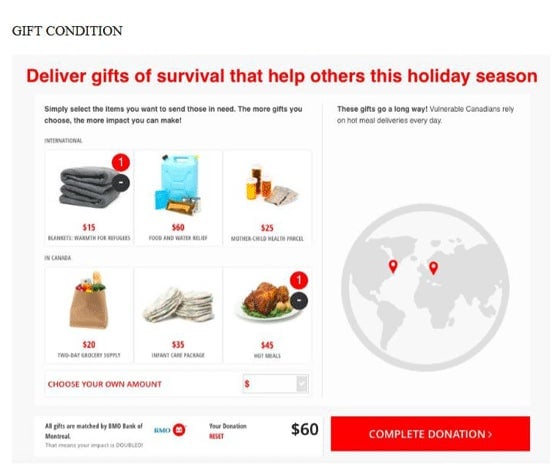

The second page emphasized specific gifts over cash donations. This page also included an image of a globe. For each new item added to the donor’s online cart, a location marker would appear in a particular geographic region, signaling that the item would be donated to that part of the globe.

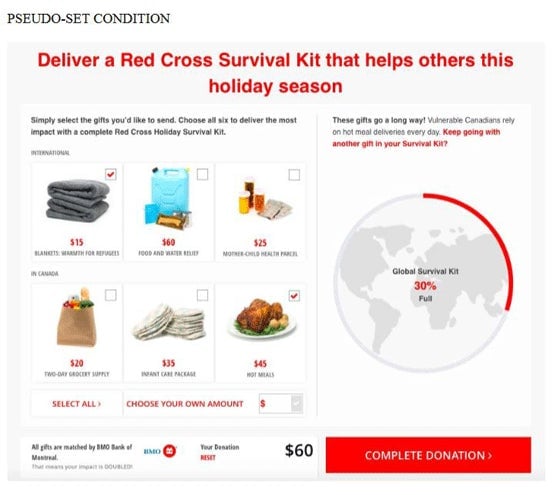

The third page invited donors to give one of each of six items in order to complete a so-called “Global Survival Kit”—in other words, a pseudo-set. This page had a globe on it, too, but instead of location markers, it featured a line that grew closer to circumnavigating the globe each time an item was donated.

The rationale: “Who wants to donate six blankets, when you can donate one blanket and feel just as good?” Barasz says. “But, if you frame it as a set, then there is a reason to want to complete the set and to donate all six of the items.”

The results of the field study were stark. Among those who chose to give gifts, 21 percent of those in the “Global Survival Kit” condition chose to donate all six items, compared with just 5 percent in the “gift” condition and 3 percent in the cash condition.

“The strength of the increase was a really nice surprise,” says Doug Wayne, director of national digital marketing and web strategy at the Canadian Red Cross, who decided to collaborate with the research team after meeting Norton through a colleague. “Ultimately, it speaks to how powerful that framing is.”

People incur the cost of a bad gamble just so they can complete a pseudo-set

In fact, the human drive for completion is strong enough that people will strive to complete arbitrary sets even when there’s a risk associated.

In another study, 201 participants had the opportunity to accept up to four online gambling opportunities, with the chance of winning up to 25 cents. (The stakes were notably low—the online equivalent of nickel slots.)

The chances of winning decreased with each successive gamble, and participants could stop and cash out at any time. Gamble 1 offered a 90 percent chance of winning a nickel and a 10 percent chance of winning nothing, Gamble 2 offered a 75 percent chance of winning, and Gamble 3 a 50 percent chance. In the first three gambles, there was no chance of incurring a loss. But Gamble 4 offered a 50 percent chance of winning a nickel and a 50 percent chance of losing a dime.

The odds were stupid. It made no rational sense to take that last gamble. And yet….

The researchers rigged the system so that all participants won the first three gambles, such that they’d all be facing the final risk having accrued 20 of the possible 25 cents. Everyone saw their successive winnings displayed both numerically and graphically on screen.

However: Half of the participants saw a visual display consisting of five nickels—with separate blank circles depicting money not yet earned. The other half saw a single quarter, divided into fifths such that unearned money was depicted as a missing piece.

Overall, 29 percent of participants in the single-quarter condition chose to accept all four gambles, compared with 16 percent in the five-separate-nickels condition. For them, the need to complete that picture of a quarter seemed to supersede their rational knowledge of the bad odds.

“People persist with completing pseudo-sets even when it’s costly for them to do so,” John says. “That, to me, is especially compelling as a researcher—that completing this totally arbitrary set is so motivating to people that they are willing to participate in an obviously bad bet.”

Future research and advice for managers

The researchers acknowledge that it’s possible for a pseudo-set to backfire. For instance, a person who might have given seven items to the Red Cross might decide to give a single set of six items instead. And a badly designed pseudo-set could prove annoying or demotivating—say, if the arbitrary set comprises 200 parts. “If the number of tasks required to fill a ‘pie piece’ is prohibitively high, people may decide not to engage at all to avoid anticipated dissatisfaction with partial completion,” the authors write in “Pseudo-Set Framing.”

Future research may investigate the ideal size of a pseudo-set in any given situation. In the meantime, Barasz offers this rule of thumb, especially with regard to encouraging people to complete repetitive tasks: “My advice to a practitioner would be to find out, on average, how many people usually complete, and then make your set slightly larger than that,” she says.

This article originally appeared on Harvard Business School Working Knowledge. Sign up for the HBSWK newsletter here.