Publishers are desperately pivoting to video—but they should be standing up to Facebook

Publishers love to pivot these days. It’s a hollow word—a euphemism meant to glaze over the truth about layoffs and the news media’s priorities. MTV News recently restructured away from long-form written content and into short-form video. Vice Media laid off 60 people to focus on video. Vocativ strategically shifted its entire newsroom—that is, axed them—to make room for, you guessed it, video.

Publishers love to pivot these days. It’s a hollow word—a euphemism meant to glaze over the truth about layoffs and the news media’s priorities. MTV News recently restructured away from long-form written content and into short-form video. Vice Media laid off 60 people to focus on video. Vocativ strategically shifted its entire newsroom—that is, axed them—to make room for, you guessed it, video.

The wild enthusiasm for pivoting has inspired a lot of gallows humor among media folks on Twitter. Anil Dash jokes: “Horse broke its leg, so we had to take it out back and help it ‘pivot to video.” Joe Brown, the editor-in-chief of Popular Science, suggests: “They should lay off 60 people from Trump administration and pivot to video.” Wired‘s Ashley Feinberg dryly writes: “congrats to vice on their pivot to video.” But as Bryan Curtis wrote at The Ringer, “behind all gallows humor stands a gallows.” And behind the gallows stands Facebook.

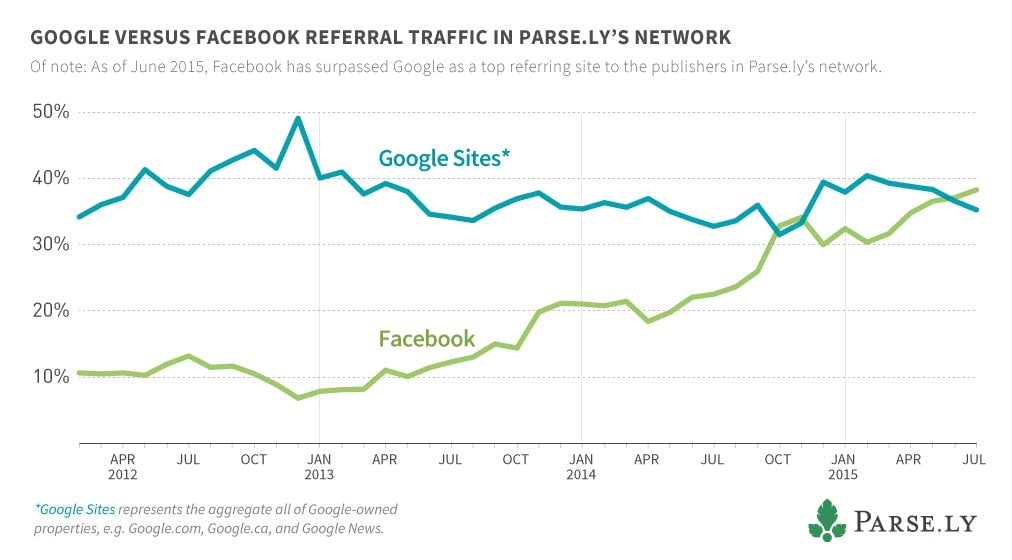

Facebook really, really wants native videos—which is to say, videos viewed on the Facebook platform—to take off. And publishers know an edict when they hear one. According to Parse.ly, a web metrics company, Facebook is the source for over 40% of referral traffic to publications’ websites. In fact, between Google and Facebook, over 80% of referral traffic to purveyors of digital news is spoken for. And Facebook’s share keeps growing.

As Facebook has pushed more traffic to publishers, they’ve become addicted to the ever-more potent stream of referral traffic to make their revenue goals. After all, you need eyeballs to sell ads against.

This reliance might seem logical. According to a 2016 Pew report, nearly half of Americans get news on Facebook. Publishers often hope that if they “go where the readers are”—which is to say, dedicate resources to make their content Facebook-friendly—they can transform some significant portion of Facebook’s audience into a loyal following.

But according to a 2017 study (pdf) by Antonis Kalogeropoulos and Nic Newman of The Reuters Institute at Oxford University, fewer than half of people who find a story from social media correctly remember which publication published it. Meanwhile, roughly two-thirds of those same people are able to remember correctly which social media channel led them to the story. This is terrible news for those publishers. How can they develop a loyal readership base if their audience can’t even remember the name of their publication?

Whether social-media users actually want to watch the kinds of videos that Facebook rewards is beside the point. “What these people are talking about isn’t even actual traditional worthwhile video,” Silvia Killingsworth at The Awl writes, without any mercy at whatsoever. “It’s a box with a play button on it just begging you for a click. It’s a glorified powerpoint presentation—slides, essentially, with words and pictures that flash and Ken Burns around the screen, sometimes with a shaded overlay.”

Undoubtedly, Facebook thinks it has good reason to shove megabyte after megabyte of panned images with awkward, obtrusive text down our eye-gullets. It claims, for example, that its users find mobile videos inspirational, that they “dial up emotion and engagement.” (As Fast Company notes: “This is all a way for Facebook to sell to marketers that video is the future, without really showing [return on investment].”) And, undoubtedly, there are reams of data—clicks and likes and attention-time—that indicate our revealed preference for bite-sized video masterpieces. (Never mind that using crappy web metrics to understand reader preference is a little like exploring Stonehenge by playing with pebbles.) But Facebook’s preference for video may also have to do with the fact that, as Brian Feldman reports in New York Magazine, “Brands prefer to buy ads against video content [rather] than text, the thinking being that consumers are more likely to sit down and pay attention to an ad when it precedes a video they want to watch than they would be if the ad simply appears next to an article they’re reading.”

Now Facebook is introducing yet another way to manipulate publishers. Last week, the company confirmed that it’s working to let publications to set up “metered” paywalls. Basically, some publishers will be able to charge users to read content delivered through Facebook’s Instant Articles. Those Instant Articles, which Facebook really, really wants publishers to use, are a super-exciting, highly efficient way to get publishers to stop worrying about having their own websites and presences outside of Facebook. In exchange, publishers get very fast load times. And while Facebook doesn’t directly goose their News Feed rankings algorithm in favor of Instant Articles (for now, anyway), having an interface designed to maximize Facebook interactions presumably means the publishers are more likely to get an algorithmic bump.

Instant Articles were already a great deal for Facebook. They gave the tech giant control over the branding and design of the articles, over the metrics that were reported, and over the data that resulted. Facebook also got a cut of the advertising revenue. But, now, with the planned addition of paywalls, it seems Facebook might want a percentage of publishers’ subscription revenue as well. (They haven’t said if they’ll take a cut just yet.)

Either way, this is another way for Facebook to keep their so-called partners in a set of golden handcuffs. As publishers sink ever-more resources into chasing fickle Facebook audiences, at the expense of finding other ways to reach their own audiences, they’ll enter a cycle of ever-greater dependence on Facebook traffic. Meanwhile, Facebook gets to take a small fee, and retain the power to make publishers pivot to video or VR or whatever ungodly, innovative thing is dreamed up next.

That’s the big danger for publishers. Facebook keeps tweaking its all-powerful, opaque algorithm. It keeps pushing publishers toward fresh pivots. And as John Herrman detailed with the rise and fall of Upworthy’s traffic from Facebook, the giant will keep changing the rules of the game in ways that will consolidate attention on-platform.

The problem is that media companies need Facebook—because they’re bleeding revenue. Not all media companies, and not uniformly, but the trends are bleak. Consider newspapers. They are only one segment of the media ecosystem, but they also produce copious amounts of original reporting, which is the lifeblood of the rest of the media world.

Here’s a look at newspapers from the Pew Research Center’s Newspaper Fact Sheet and the American Society of News Editors’s Newsroom Diversity Survey:

Faced with the loss of billions of dollars of ad revenue and tens of thousands of jobs, it’s tempting to hunt for an easy culprit. For example, there’s Craigslist, which disrupted the classified advertisement market away from newspapers to the tune of at least five billion dollars.

Some argue that the decline of the newspaper—and the broader peril of the media ecosystem—can’t be pinned on any one company. It’s the internet in general that’s to blame. Digital ads just don’t pay as well as print ads. People expect news content for free. Newspapers weren’t good custodians of classified ads anyway.

That’s all true—up to a point. But then we come to Facebook. Facebook—and to some degree, Google—are hoovering up the internet’s ad revenue. As John Herrman reported last year at The New York Times, “In the first quarter of 2016, 85 cents of every new dollar spent in online advertising will go to Google or Facebook, said Brian Nowak, a Morgan Stanley analyst.”

Facebook has overwhelming scale and resources. But its desire for more video, its invitations to Instant Articles: these are not opportunities. They are the whims and the self-interested pleas of a tyrant.

I know publications have to work with Facebook: Facebook has unquestionable scale, and if publishers want access to it, they’ll need to give up something. But they don’t need to pivot on command. As Matthew Ingram notes, “Facebook is taking some sustained fire for its dominance of the advertising industry (along with Google), with the News Media Alliance arguing its members should be exempted from antitrust laws so that they can present a combined front in bargaining with the digital giants.” It might be time for publications to band together to stand up to Facebook—rather than be taken, one by one, into Facebook’s crushing embrace.