Selfies are just the contemporary version of the art masters’ self-portraits

What kind of self-portraits would art’s great masters have offered had they had access to smartphones? “To hell with sketchings, spatial perspective, and density of brushstroke,” I imagine Van Gogh venting in an exhale of pipe smoke. “I’m just going to snap a selfie.”

What kind of self-portraits would art’s great masters have offered had they had access to smartphones? “To hell with sketchings, spatial perspective, and density of brushstroke,” I imagine Van Gogh venting in an exhale of pipe smoke. “I’m just going to snap a selfie.”

In the 17th century, only a handful of people on the planet had the skills, materials, and tools needed to create public self-portraits. Now sophisticated smartphones help us indulge that burning urge to tell the world about ourselves, showing them what we find noteworthy about our faces, enviable about our vacations, and interesting about our boredom.

The cult of selfie-taking has mushroomed since the term first entered public usage in 2002. Improvements to front-facing cameras on smartphones in the mid-2000s permitted quicker, better selfies, and their popularity grew so much that “selfie” was deemed the Oxford Dictionaries’ Word of the Year in 2013. On average, 93 million selfies are taken across the globe each day, and millennials spend about an hour per week dedicating themselves to Instagramming them.

I stumbled onto Saatchi Gallery’s “From Selfie to Self-Expression,” the world’s first exhibition exploring the history of the selfie, after a toss-off mention by a British friend. I grudgingly went, nursing a stiff dose of cynicism due to the growing trend of gimmicky, “high-concept” blockbuster-aspiring exhibits, which are the art world’s equivalent to click bait. I wanted to dislike this exhibit as much as I thought I disliked selfies—I never really got the selfie or its appeal. But I couldn’t.

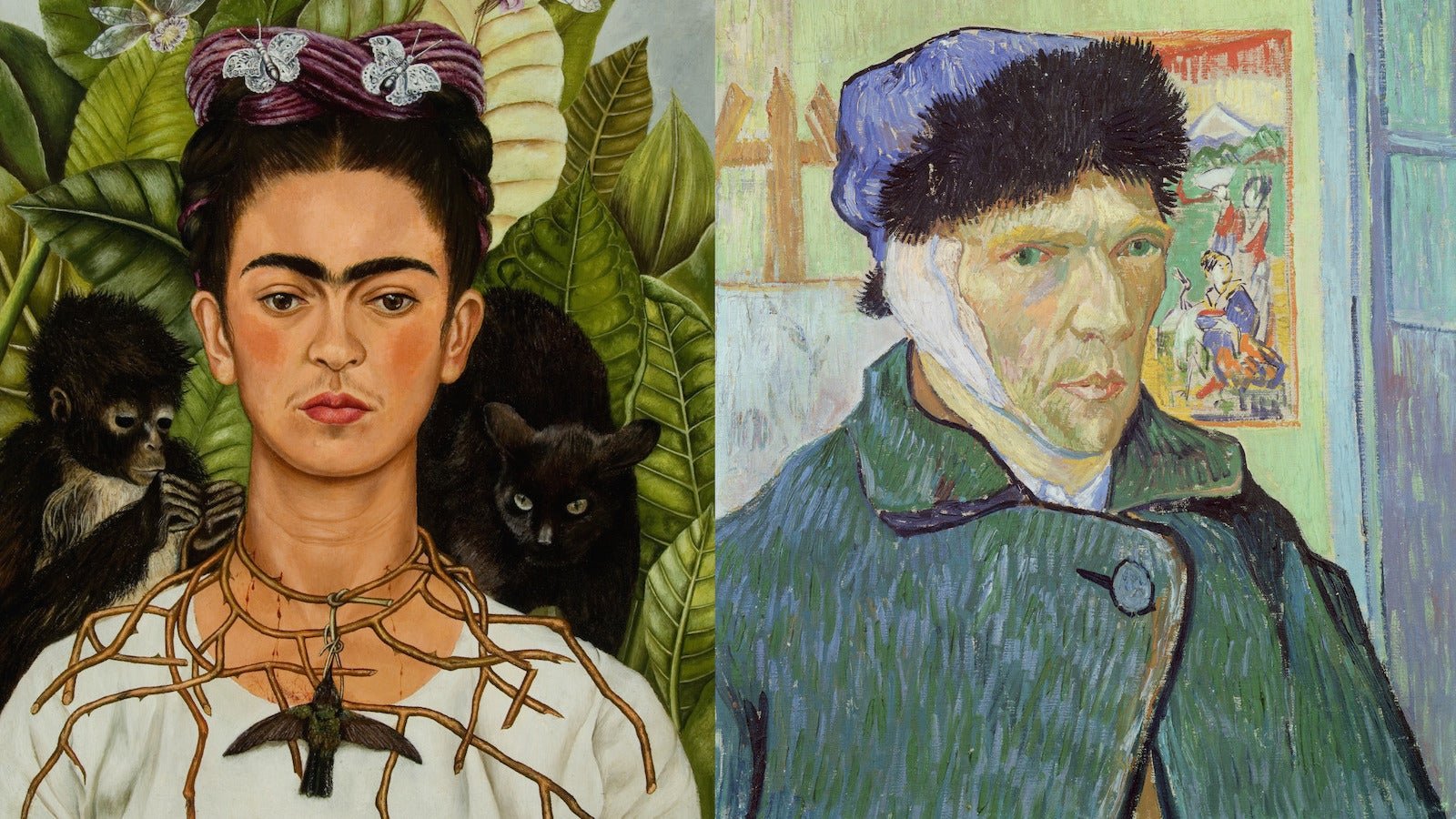

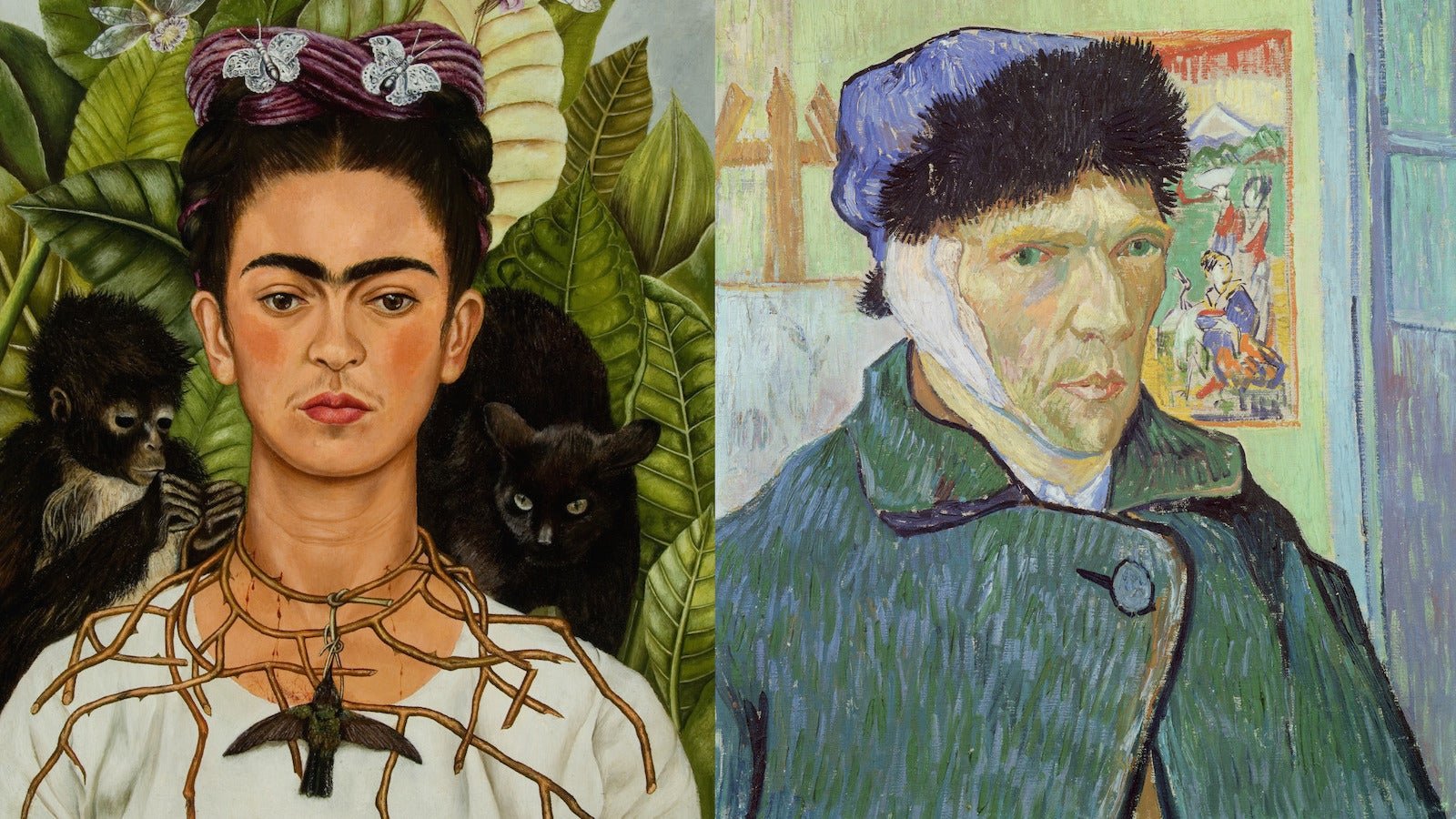

“From Selfie to Self-Expression” captures self-portraiture in all its forms and its power to reboot how audiences understand art. The exhibit begins with canonical self-portraits of renowned painters digitally displayed on enormous flat screens. They look like oversize iPhones: Diego Velazquez’s “Las Meninas” (1656), Rembrandt van Rijn’s “Self-portrait with Two Circles” (c. 1665–1669), Edvard Munch’s “Self-Portrait” (1882), Vincent Van Gogh’s “Self-Portrait with Pipe” (1886), and others. You experience these classic paintings as if they’re selfies on your smartphone, moving past each like a swipe. You are even given the option to touch the screen and “like” each one. At the time of writing, the painting with the most likes is Frida Kahlo’s “Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird” (1940), which has 42,055 likes to the 24,262 likes of Van Gogh’s “Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear” (1887–88).

Why? Perhaps viewers like Kahlo’s self-portrait more because it conforms to our polished expectations of the selfie. By contrast, Van Gogh’s appears rather brutal. Painted just after he’s lopped off his ear, it doesn’t present himself as something more or different than he is; its brutal honesty isn’t trying to broker a kind of social-media currency. It’s about the artist’s aging process, his psychological and physical damage, and how his existential crisis defines his formal self-presentation to the world—and that’s not normally what a selfie seeks to project. On the other hand, Kahlo’s self-portrait is a construct of how this witty woman would like to be perceived, coyly play-acting as if staged on holiday or a nonchalant garden party. This is more attuned to how most people take and post selfies: posed, fantastical visions of the best versions of themselves.

The gulf in the number of likes between a Van Gogh and a Kahlo makes you reflect on how audiences consume art alongside the chaos of social media. Museum art is traditionally presented as untouchable, unassailable; the works are digested, exhibited, and explained as being important to history and to you without the audience exchanging any judgement of the work. But that’s just not how we interact with images anymore.

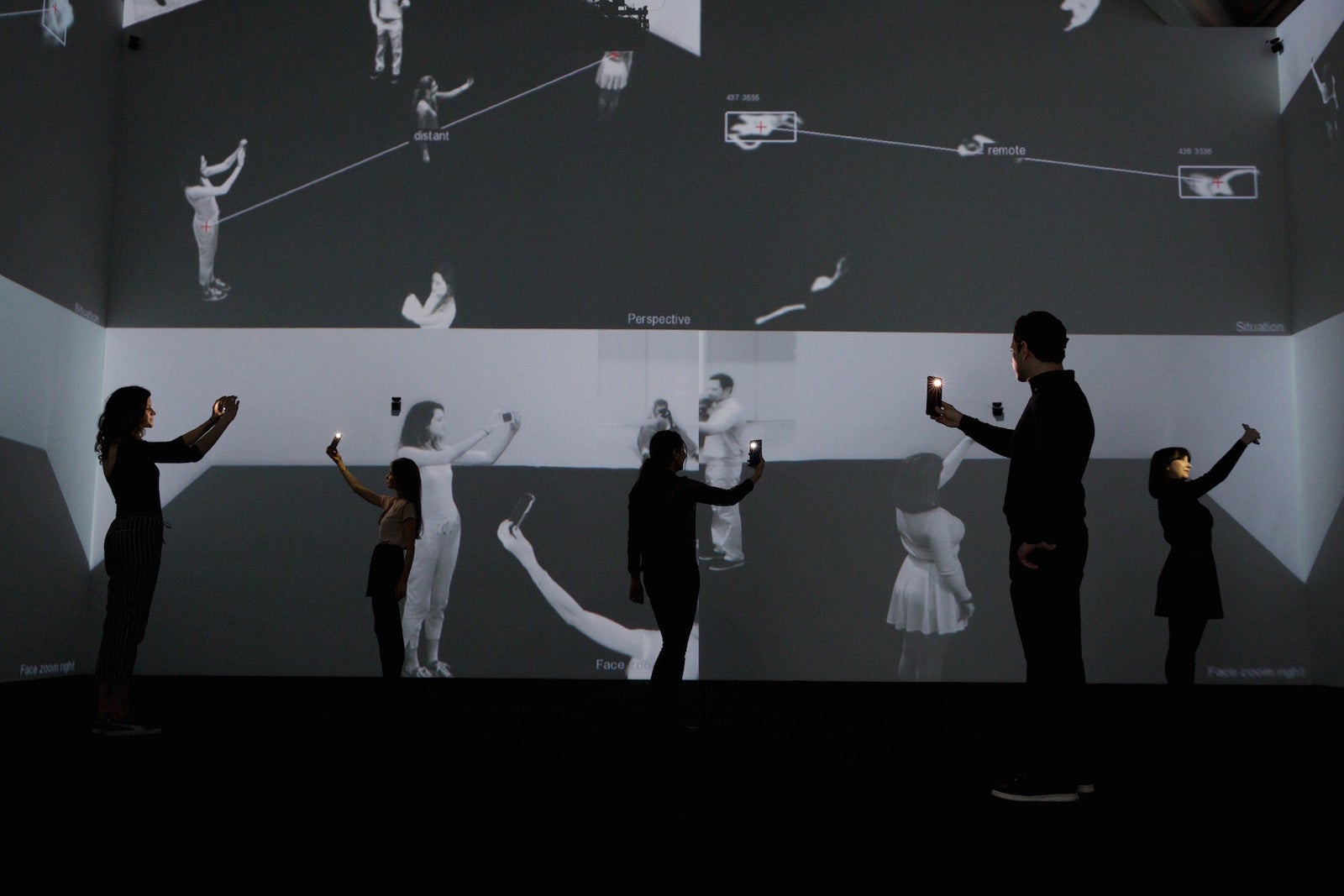

Saatchi Gallery’s exhibit seduces us to engage with images in impulsive, unexpected ways. In “Zoom Pavilion” by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and Krzysztof Wodiczko, you enter a cavernous room surrounded by black-and-white surveillance footage monitoring the entire space. Cameras capture and loop your every movement and project it onto the ceiling and walls. The work’s computerized surveillance systems use facial-recognition algorithms to detect the viewers’ faces and magnify them up to 35 times larger. Different angles, different scales, and in 360 degrees spanning the room, your face is in digital crosshairs. I and other visitors instantly began taking photos of our physical selves, then snapping photos of our images on the walls, thus taking meta-selfies. It is a brute, bewitching cycle of people under surveillance who cannot help but document themselves being documented.

In that instant of ecstasy beholding yourself as digital art, you may either fixate on the exhibit’s context or overlook it: This art institution tracking you sits in one of the most surveilled cities in the world. London, according to latest estimates, has roughly 422,000 closed-circuit cameras, or roughly one for every 14 people, operated by the state, private businesses, and wealthy individuals. “Zoom Pavilion” flips the sinister act of surveillance on its head into a rush of fevered adrenaline.

The exhibit ends with the results of a worldwide selfie contest that opened the doors to user-generated art and punctured the elite gate-keeping that prevents unknown artists from exhibiting at an international gallery. “We challenged people to be as creative as they could be with these selfies,” says Nigel Hurst, CEO of Saatchi Gallery and the exhibit’s curator, over high tea in the gallery. “People are telling a story about themselves.” 14,000 selfie enthusiasts from 113 countries submitted selfies to the gallery’s competition, and the 10 finalists’ selfies were unexpected and stunning: from Finnian Croy of Glasgow, whose formally precise, double-mirrored selfie rejects the sloppy genre common on hookup apps, to Deborah De Haes of Hoeselt, Belgium, whose face and body is completely hidden behind long tendrils of her knee-length hair, posed in a garden, seemingly riffing on Eve.

The public’s contributed selfies prove more absorbing than the golden hits in the exhibit’s celebrity selfie gallery, such as the Barack Obama, David Cameron, and Helle Thorning-Schmidt selfie at Mandela’s memorial service in 2013 and Ellen’s 2014 Oscar selfie, which broke the record for the most retweeted tweet ever. Sure, humdrum narcissism lurks in some entries—but in odd, vulnerable ways, the public’s selfies prove as extraordinary as the masters’ self-portraits. Most reveal an arresting yearning and a deep creative purpose; they effortlessly expose a range of expressions from touching banality to formidability.

“From Selfie to Self-Expression” is a comparative, populist scrum that erases the distinction between selfie and art. You are seduced into bringing your own experience, baggage, likes, and dislikes to this dialogue. It adds to the narrative of how contemporary artists respond to our convulsing image culture, and how we respond to surveillance and exhibitionism. “The art world can either embrace the selfie or not,” Hurst says. “But because the selfie is a tool so many people choose to use, you ignore it at your peril.”

Brought full circle, classic self-portraits are deftly landed into the context of the selfie, and the selfie into the context of 500 years of classic self-portraiture. If selfies are the bastard stepchildren to classical art, those ostracized children reveal more about their parents than they might care to admit. All those misfits suffering from demons in their respective day left me thinking about selfies in a more creative, less pouty kind of way, and about classic art more intimately.

My skepticism has surrendered. And so, the only way I could think to end tea time with the exhibit’s curator is to extend my arm, lean in to him, and snap us a selfie.