Lush, a great UK success story, is helping its workers leave Brexit Britain—and keep their jobs

Poole, England

Poole, England

Mark Constantine, co-founder of the British cosmetics company Lush, is a notoriously difficult man to interview. He can meander. When asked about Brexit, Constantine instead goes on about the thousands of birds that fly through Poole Harbor, which his office overlooks. It’s remarkable how free these birds are to roam the sky, he says, traveling from as far as Africa to the Scottish highlands. He pauses, then laughs before finally getting to the point: “I’m a wishy-washy liberal who doesn’t believe in borders.”

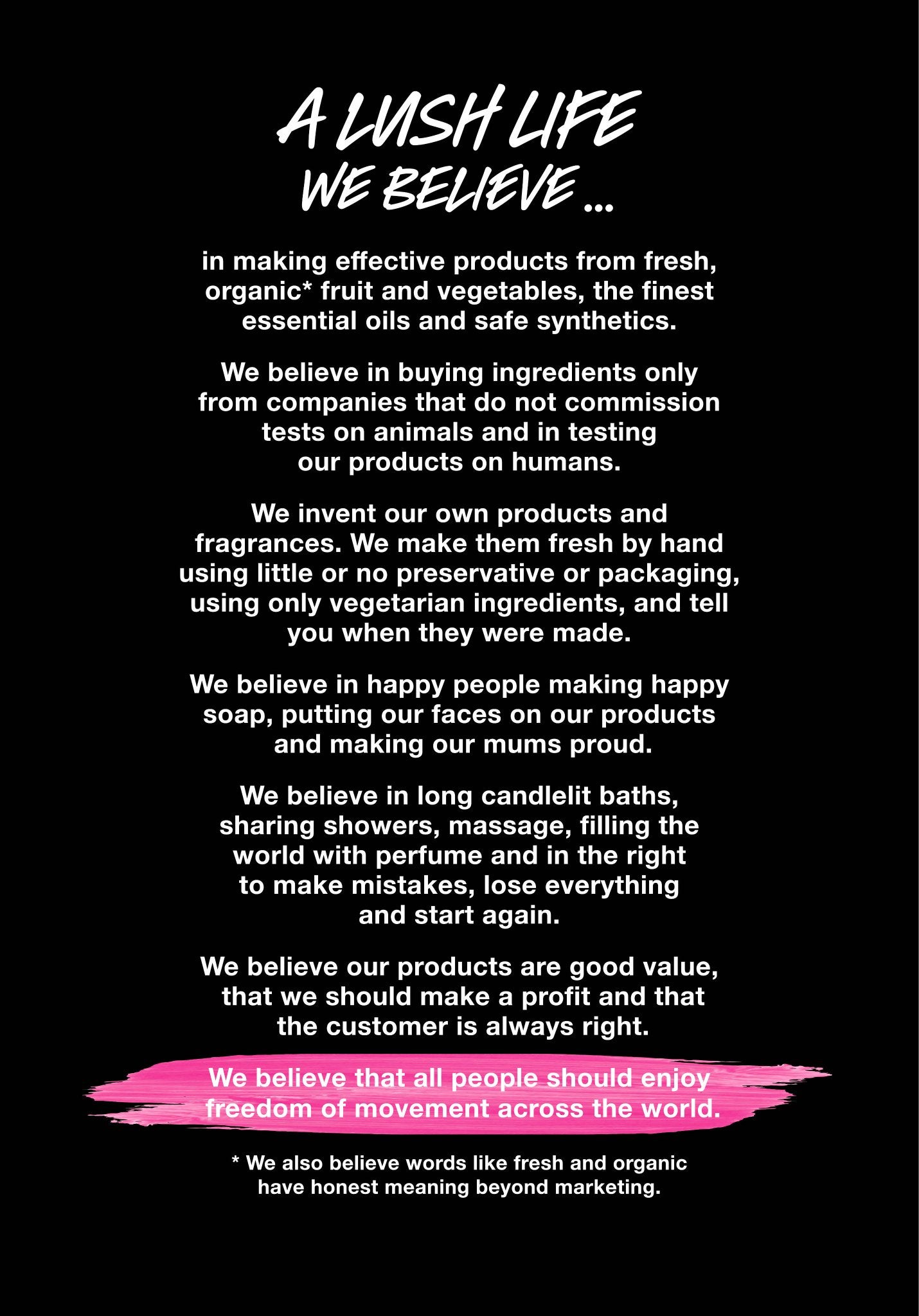

When Lush was created, the founders came up with a statement of core beliefs and values, which included “long candlelit baths, sharing showers, massage, filling the world with perfume and the right to make mistakes” and of course making “our mums proud.” The “we believe statement,” found in most Lush shops across the world, has been amended for the first time in more than two decades. Within its commitment to hand-making products from fresh, sustainable ingredients and aiming to offer good value, this quintessential British business now also asserts its belief that “all people should enjoy the freedom of movement across the world.”

The addition of these words is a response to the UK’s historic vote to leave the European Union. It marks an important shift; Lush is now leading a fierce defense of people’s right to travel, study, work, live, love, and retire across the world. The company has a so-called “freedom of movement” hub with advice on citizenship and what rights people have after Brexit, and it is campaigning to keep immigration routes open for all people. While some companies are quietly lobbying the government (paywall) to relax rules on immigration, Lush is taking its message public.

Since the Brexit vote, Lush’s “first, second, and third” priority is protecting their EU workers, ethical director Hilary Jones says: “We’ll bend over backwards to make sure none of our staff lose their jobs because of Brexit.”

At Lush’s headquarters in Poole, on the south coast of England, 1,025 people work in the factory. Just over half (516) are EU migrants. Jones remembers clearly the morning after the Brexit vote; she had never seen so many in the company “cry so much in a single day” she says. Walking around the factory, she found “the uncertainty and fear was palpable.”

Lush is offering a way out for its workers; the opportunity to move and work in its newly up and running factory in Düsseldorf, Germany. The company signed its lease in November 2015—seven months before Britain voted to leave the EU. The factory was initially “a minor player,” Jones says, intended to provide fresher products for some of its European market. But since the vote, the Düsseldorf site has become a kind of “salvation,” she says—for both the business and its workers.

A total of 63 staff have taken up the offer to relocate to Germany—20 from the UK and 43 from other nationalities. It’s not just EU workers picking up and leaving—some of their British colleagues are not interested in sticking around to see what post-Brexit life will be like.

When EU workers came to save the day

Lush is largely known for its heavily scented high-street shops peppered with candy-colored bath bombs, face-mask mixtures, and hair products boasting ingredients like resin from the inaccessible climbs of northern Laos to the bitter orange trees of Tunisia. In Europe, a large number of these products are made in the Willy Wonka-like factory in Poole.

Factory workers were predominately white and British in the early years after Lush was founded in 1995, according to Joe Craven, who started working for the company in 1997. He took an entry-level job when he was just 16, putting together Lush’s iconic bath bombs, then slowly worked his way up to recruitment manager. Craven fell in love with the company in his first week—he enjoyed debating politics and ethics with the colleagues he calls “a big bunch of misfits.”

The company grew rapidly from the early 2000s. “We’ve had years we simply couldn’t keep up with demand,” Jones says. Craven turned to the local job center for both temporary and permanent workers for entry-level jobs, but he says they stopped sending applicants within a few weeks. (He says the center had run out of possible candidates).

UK unemployment was particularly low then. The rate had nearly halved between 1993 to 2003 (to just 4.8%). In 2004, the rate in Poole was nearly half that of the UK. (In 2017, UK unemployment stood at its joint lowest rate since 1975).

Craven describes 2005 as “a big year”—Lush was eventually saved by an influx of migrants. This change was largely driven by the UK’s decision to not put immigration restrictions on the eight eastern European countries that joined the EU in 2004 (the UK was one of only three EU states not to do so). The government had expected up to 13,000 eastern Europeans a year to come to the UK. Almost 580,000 arrived in just two years. According to one historian, this resulted in “the biggest influx of immigration in English history, causing the fastest increase in population ever recorded.”

In Poole, the non-UK born population increased from 7,000 in 2005 to 16,000 in 2015. According to the 2011 census (pdf), there was a 20-fold increase of Polish-born residents in a decade; they made up 1.1% of the non-UK resident population in Poole in 2001—and 13.1% in 2011.

“It was a godsend for us, and we think a godsend for Britain,” Jones says. The influx meant Lush was able to plug labor gaps during its busiest period—the run-up to the Christmas shopping season. The company grew rapidly, hiring seasonal workers from September to December. Permanent jobs then went to the most enthusiastic. Last year, after conducting 300 interviews, the Poole factory hired 1,500 people for August to December employment. Many migrants were happy to work for those months, and then return to their home country.

Easy access to more workers was crucial to Lush’s rapid expansion. The company now has 920 stores in nearly 50 countries and factories in seven. For the year ending June 2016, the company generated revenue of £723m ($943m), an annual increase of 26%, and pre-tax profit of £43.2m (an increase of 76%). Lush’s profit figure was measured after setting aside funds of £6.9m for charities. (Lush spends millions funding direct-action groups).

None of it would have been possible without freedom of movement, Jones says.

The international mix brought its own challenges. Language became a barrier to migrants eager to win promotions. “We suddenly realized we had all these people and they were stuck,” Jones says. Many didn’t have enough time outside of work to learn English or the resources to do so. Lush decided to provide free English classes, during work hours. Migrants who had known very little about the UK when they arrived were now running multimillion-dollar departments.

Lush’s openness on migrants sparked some local backlash. Nearby residents would tell Craven he worked for “PoLush” (a portmanteau of the words Poland and Lush), and would badger him to employ more British workers. There was even resentment within the factory. Some British workers felt the company was going to extraordinary lengths to support EU workers, but not them. For those annoyed by the language lessons, Jones would point to the fact that the help offered to migrants didn’t block Britons from moving up in the company. For example, Craven started working for Lush out of school and with few qualifications, yet he’d been able to rapidly advance. “We want a fair and inclusive company,” Jones says, which meant removing any “unfair blockages,” be it language or qualifications.

Even amid the challenges, workers describe Lush as one big happy family. There are also actual families at Lush, Lush couples, and now Lush babies. It’s common to see mothers and their adult sons or daughters working alongside each other. They have had great reason to feel at home, until now.

Brexit wins, illusions are lost

Few at Lush thought the referendum on Britain’s EU membership would result in an exit. From the temporary staff who make the bath bombs, to the managers of exclusive products, and even the co-founders of the company, the feeling was the same—Britain wouldn’t do something as insane as leaving the EU.

They were wrong. Britain voted to leave by a margin of 52% to 48%. Poole had voted to leave by an even bigger margin, with 58.2% wanting out.

Gosia Malgorzata, a Polish migrant who had moved to the UK a decade ago (and now manages the Toothy Tabs factory), was devastated. “Every second person isn’t happy we are here,” she says. Her husband, Bart Bartosz, who manages the soap factory, said members of his team were frantic for answers. When he went home, their son was asking the same questions: “It was difficult to explain to our seven-year-old son what happened.”

Britain voted to leave the EU more than a year ago, leaving migrants in a protracted legal limbo. That’s proving to be divisive in the Brexit negotiations now under way. In the UK, 3.5 million EU migrants will have to register to establish post-Brexit status. Britain has offered EU migrants the right to live, work and access certain benefits after they’ve lived in the UK for five years (officials have yet to clarify the cutoff date for this deal). The UK’s proposal falls short of the EU—which wants to give migrants the right to bring family members to the UK and have guaranteed access to benefits, health care, and education.

The uncertainty was what was most difficult for 27-year-old Vendula Zlamalova. She had migrated from the Czech Republic to the UK in 2013 and started work at Lush. “It was like discovering a new world,” Zlamalova says. She felt like a giddy child in a candy store when she first stepped into the Poole factory, “excited to work with different fruits, flowers, herbs, spices, honey and milk.”

After Brexit, she suddenly felt like she needed to look over her shoulder when walking home. She remembers feeling ashamed for talking to her brother in Czech. “I felt people were judging me for talking in my own language,” she says. As the referendum results came in, Zlamalova’s boyfriend, Ryan Matthew Tubbs, a 25-year-old Brit who was born and raised in Poole, teased that she might have to leave the country. When the votes were counted, it was no longer a laughing matter.

Tubbs, who has worked for Lush since he was 20, had toyed with the idea of moving before. After the result, Tubbs describes the decision as almost instantaneous. “It feels like the majority of this country aren’t the same sort of people I am and I don’t want to stay around that,” he says. Zlamalova and Tubbs moved to work in the Düsseldorf factory in October.

Becca Pugh, another Brit who now works in Düsseldorf, shares that frustration. “I feel lost in my own country. It’s really sad,” she says. Since moving to Germany, Pugh has fallen in love and built a new home for herself. She says she’s saddened by the thought that the next generation of Brits could miss out on such opportunities. “I’m staying here for a good while,” she adds.

Zlamalova says there are a lot of Brits in the German factory who do not want to come back, adding “they don’t want to be a part of that environment.” Maddy Ross, a 24-year-old Australian who moved from Sydney to work in the German factory in December, echoes Zlamalova’s point, saying, “English is one of the biggest nationalities here. A lot of people don’t want to go back.” As for herself, Ross admits she had always envisioned living in the UK. “That was once a dream, but I’m not sure now,” she says, adding that from a foreign-worker’s perspective, what’s going on in the UK “feels a bit chaotic.”

The exodus has been particularly severe with EU migrants. Patricia Fernandes Pereira, who works on the manufacturing payroll team in Poole, is starting to get worried. “A lot of my staff are leaving now to go back to their country,” she says.

Those who left include 35-year-old Lithuanian migrant Andrius Antanaitis, who first started working for Lush’s Poole factory in 2012. Once Britain had voted to leave, Antanaitis knew he wanted to leave too. He didn’t know what was going to happen to people like him, nor was he particularly interested in jumping through hoops to stay. “You feel second grade, having to go through all that process again.”

Lush created a new role for those who do want to stay in the UK, an advisory position to look after staffers’ immigration needs. Nikki Williams, an American who had worked in Lush for over a decade, calls herself the freedom of movement officer. Since Britain voted to leave the EU, Williams set out to make something as complex as migration law simple. Williams has led information sessions for both EU and British workers on their current rights. If people want to work with the solicitors, Lush has arranged a special fee and offered a loan.

How Lush is picking up the pieces

Since Britain voted to leave the EU, migrants have left the country in droves. Net migration, the difference between the number of immigrants entering the UK and those leaving, was estimated to be 248,000 in 2016—down 84,000 from 2015. The drop was largely driven by a “statistically significant increase” in the number of migrants leaving the country, the Office of National Statistics note.

Immediately after Brexit, Lush’s senior management went from monthly meetings to meeting every single week, Constantine says, adding they had to debate every UK investment. “There was no board that met the day after Brexit to work out how they can increase business in Britain,” he explains.

The Düsseldorf factory has grown rapidly. From March 2016 to the end of July, it was only supplying Germany. The factory is now supplying five other markets (France, Holland, Luxembourg, Czech and Belgium). While it was always the plan for the German factory to supply fresher products to some European markets, Lush said in a statement last year that it had “done it with a bullet” following the Brexit vote.

If the government pursues a so-called hard Brexit (where Britain leaves the single market and the customs union), Constantine and Jones say they’ll be forced to do more business abroad. The British government has confirmed that freedom of movement will come to an end in March 2019. Constantine describes the move as “anti-business.”

Lush is particularly worried about a skills shortage. The company is lobbying the government to put the role of “master compounder” (the title Lush uses for its workers who create the more special and unique products by hand) on the officially protected list.

Lush isn’t the only company worried. Across the UK, businesses have called on the government to ease immigration restrictions. One British farmer pointed out that he’s had one Brit apply for a job picking fruit in Surrey—and that man left after his first day (the work was reportedly too hard).

Any dramatic reduction in immigration will also hit vital services. “The NHS [the national health service] is a classic one, where it’s essentially reliant on EU citizens working as doctors and nurses,” says Thomas Cole, head of policy and research at Open Britain, a private group fighting to keep the UK in the single market and customs union.

Any significant drop in immigration will come at a price. In 2016, the UK Office for Budget Responsibility forecast that lower migration could end up costing £6 billon ($7.7 billon) a year by 2020-21. Cole points out that EU migrants put more into the economy then they take out in benefits; a reduction likely will mean the government will either have to raise taxes or cut services. The government has to be willing to ask the public, “Are you willing to accept the economic consequences?” says Cole.

That view from the harbor

Constantine is keen to stress that support for migration should never be about access to cheap labor, but centered on what he calls “inspired labor”—driven people who have the enthusiasm and talent to transform businesses.

With that, Constantine goes back to his beloved birds. He’s keen to point out that the species that have become synonymous with the romantic British countryside—nightingales, cuckoos, and British skylarks—are declining rapidly. Intensive farming has been blamed for the loss of many varieties. “They’ve just destroyed it all,” he says.

For Constantine, it’s about defending the backbone of British culture and society; from the nightingales that inspired John Keats’ most famous poem, to the Polish migrants putting together everyone’s favorite bath bomb. “They’ll have to nail me to a cross before I accept there are differences between this person and that person,” he says and laughs again.

For a man ready to take on the British government and more than half the country, he looks remarkably relaxed.