The weird, elegant, and hilarious Flash projects that set the tone of the modern internet

These days, Adobe Flash is derided as clunky, slow, and insecure. It triggers memories of fighting with browsers to get the plugin to work, of waiting through loading screens just to get a bit of information, and generally having a bad time on the internet. We look back now and laugh at its big buttons and convoluted interfaces, the stuff once thought to be the future of the web, and we can hardly believe we were so silly.

These days, Adobe Flash is derided as clunky, slow, and insecure. It triggers memories of fighting with browsers to get the plugin to work, of waiting through loading screens just to get a bit of information, and generally having a bad time on the internet. We look back now and laugh at its big buttons and convoluted interfaces, the stuff once thought to be the future of the web, and we can hardly believe we were so silly.

In our continuing march toward a better, faster, more responsive web, Flash content—the good along with the bad—is being trampled over and disregarded, slowly disappearing from hard drives in personal computers and server farms alike. And by the end of 2020, according to announcements made this week by Adobe and all of the major web browsers, support for the Flash Player plugin will end, and we’ll collectively pretend the whole thing never happened.

The thing we’re all too quick to forget, however, is that it wasn’t all bad. Flash—originally called FutureSplash and renamed by Macromedia in 1996—provided amateur animators with an intuitive app for creating web-based cartoons without having to code. It gave news organizations a new way to convey information. It allowed video-game developers to put their games in front of eager players without the help of big publishers or consoles. Flash was a portal through which weirdness and even elegance entered the internet, and it set a tone that is still with us today.

Below are five iconic Flash projects that illustrate that tone, and will likely remain relevant even after Flash has disappeared.

Newgrounds

Before Farmville and Candy Crush invaded your Facebook notifications, there was Newgrounds. You won’t find a post or comment thread about early Flash games that doesn’t prominently feature nostalgia for the site. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, founder Tom Fulp introduced Flash games on the website, some of which he made himself, and some that were submitted by the site’s users. Newgrounds eventually grew to include a library of more than 80,000 Flash games—far too many to pick just one, so we asked Fulp to tell us which he feels best represents the site, and Flash as a game medium.

“Abobo’s Big Adventure stands out to me as an iconic Flash project,” Fulp said in an email. “Started in 2002, it didn’t release until 2012 due to the massive scope and number of games it lampooned. It also might have the funniest ending of any video game ever.”

As you can see in the trailer above, Abobo’s Big Adventure is a spoof of just about every classic Nintendo game, changing its entire play style for each game it parodies. Although it’s just five years old, the game was born out of the clever weirdness that Newgrounds embraced, and has permeated in the modern independent games industry.

“To me, the greatest thing about Flash was how easily a programmer and artist could collaborate in a shared space,” Fulp said. “It really spawned a lot of creative games over the years. Growing up, I would make text-based games in PASCAL and cartoons in Deluxe Paint. I always dreamed of a software that would merge code with animation. Flash was that for me.”

Fulp recently wrote a blog post on Newgrounds about the end of Flash, and says that the site now supports games made with JavaScript and HTML5, and that he’s working on archiving the site’s massive library of Flash games.

The End of the World

“Hokay, so, here’s the earth.”

The End of the World (or End of Ze World) was a viral video that happened before viral videos were called viral videos. It first spread around the internet as a Flash animation in 2003, and within a year was commonly quoted by young internet users as much as any Hollywood blockbuster. For many years, every hilarious person on the web was always “le tired” or “le something,” and you could probably find an instance of it in a Reddit thread right now, if you looked.

In a 2015 interview with Mic, creator Jason Windsor was asked whether he believes the video “played a role in ushering in a new age” of the internet.

“I like to think that it helped the progression of funny Flash videos and animated internet videos,” Windsor said. “As far as ushering in a new age, I don’t know. I hope that it progressed that medium, anyway. But that’s sort of how things are on the internet—it’s so exponential, a bunch of people see one thing, and then it just—it is so explosive.”

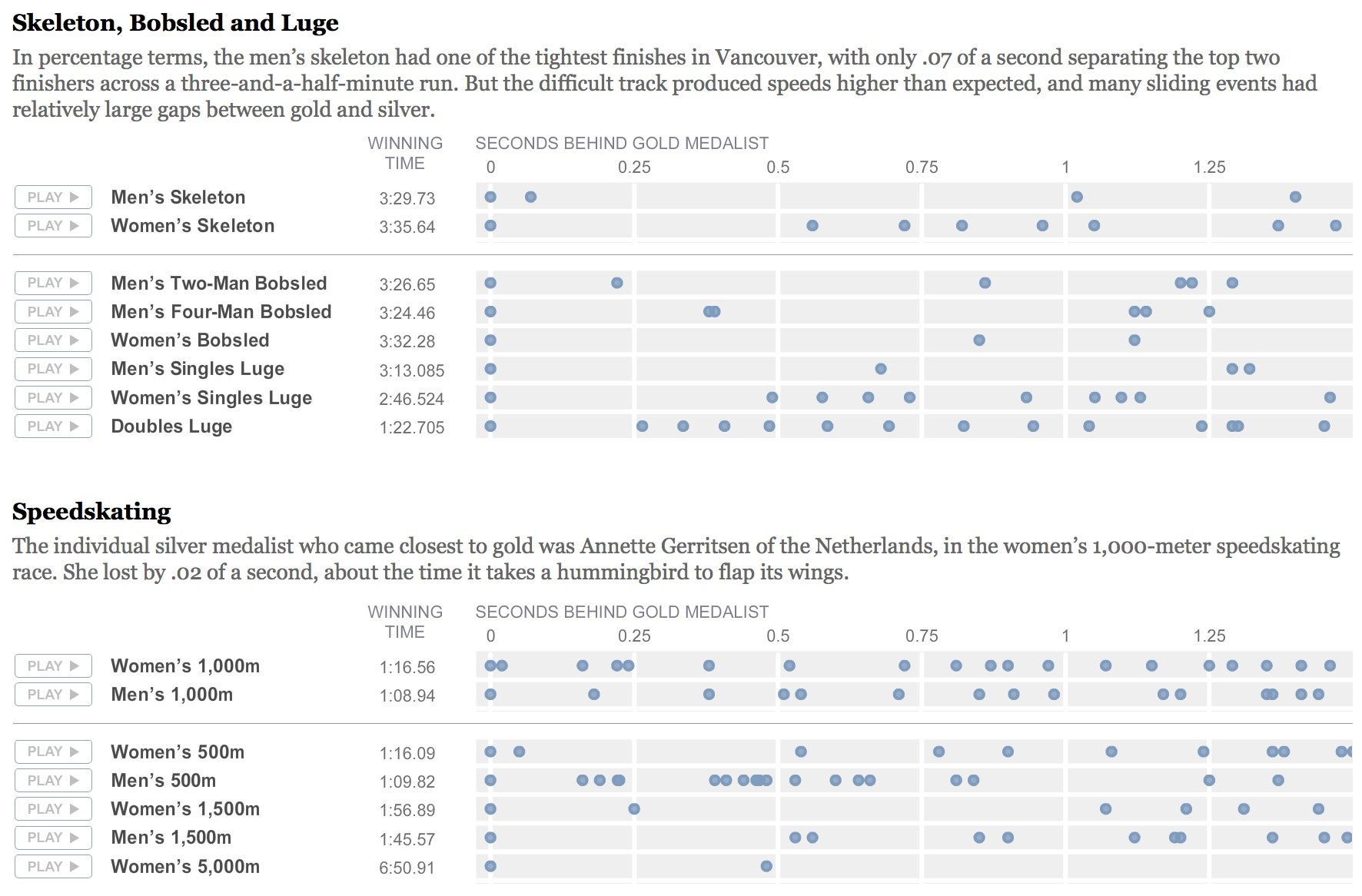

Fractions of a Second: An Olympic Musical

By 2010, many American newsrooms had experimented with Flash, attempting to bring interactivity to the data graphics they published in their newspapers every day. But capturing the clean, elegant style of typical newspaper charts and graphs proved difficult in a medium that tended toward the clunky and convoluted.

Several graphics had broken out of that pattern in the later days of Flash, but none set the tone for what interactive news graphics would become in the following years quite like “Fractions of a Second: An Olympic Musical” by Amanda Cox.

The series of charts illustrates, well, the fractions of seconds that can mean the difference between an Olympic gold, silver, bronze, or not placing at all. Pressing the play button beside each category lets the reader see, and hear, how small those differences are, as the dots on the charts light up and play a piano note at the exact finishing time of each competitor. Cox noted in the article that, for example, in the Women’s 1,000-meter speedskating competition, the silver medalist came in behind the gold medalist in “about the time it takes a hummingbird to flap its wings.”

“Flash was a nice transition from print: a set size, just fill a box, none of the browser compatibility headaches of the IE8 era,” Cox, now editor of the Times’ Upshot, said in an email.

Upshot’s deputy editor, Kevin Quealy, pointed out, however, that those features and Flash’s inability to respond to difference screen sizes may have distracted graphics editors from the changing nature of the web, and the devices that were accessing it. Cox agreed.

“If we’re being honest, it probably set the information graphics field backwards on the whole,” Quealy said.

While that may be true, through graphics like “Fractions of a Second,” Flash provided an early glimpse of what news graphics could be, what they could look like, and even how they could sound.

Homestar Runner

Launched in 2000, Homestar Runner was a series of animated Flash cartoons that most early internet users will remember for its strange, irreverent humor that spun into multiple stand-alone series and alternate realities. Like End of Ze World, Homestar Runner was a viral hit before viral hits were a thing, attracting millions of hits each month in the early 2000s.

Adobe’s recent announcement on the death of Flash was just the latest confirmation of what everyone already knew was coming: Indeed, the creators of Homestar Runner released a video on YouTube in 2015 entitled “Flash is Dead!”

In it, the cartoon’s two main characters, the titular Homestar Runner and Strong Bad discuss the end of “what we breathe, the thing what creates us all!”

“I’ve got enough classic motion tweens and deprecated actions in old f-sack here to last us at least six months until we can learn HTML5,” Strong Bad says.

“Oooh, I know what that stands for,” replies Homestar. “Hypertext markup lotion!”

Episodes of the series have now been converted to videos and uploaded to YouTube, but the original site—Flash and all—is still up and running.

Frog Fractions

Frog Fractions is, ostensibly, an educational Flash game that helps the player learn about fractions. But as one progresses through the game, which starts out as one about a frog catching flies with his tongue, they learn the game doesn’t teach them anything about fractions.

As the player progresses, they can spend points on upgrades to help the frog catch more bugs. Those upgrades include a dragon and a cybernetic brain. Eventually, once the player obtains a warp drive, they can travel on the dragon to Bug Mars, where an ensuing altercation lands them in Bug Court. And it only gets more surreal from there.

“Flash was a huge part of what made Frog Fractions work,” said the game’s developer, Jim Crawford, in an email. “For years, Flash was considered a toy, used for producing cute animations and trifling time-waster games. By the mid-00s, it had grown into a platform that you could build something serious with, but the reputation had stuck. Frog Fractions played right into this: it’s easy to believe that a browser game about a frog eating bugs is a game you pass the time with on your lunch break.”

Crawford pointed out that Flash offered game developers features that made it easy to deploy games that behaved in exactly the same way in every browser—something online games made with HTML5 and Javascript still struggle with today.

“I’m building games in Unity now,” he said. “I’m making Windows executables, because Windows executables from 20 years ago still run. At least for now.”